EU’s Ability to Act

Introduction

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marks a true turning point in the history of contemporary Europe. In 2016 the election of President Trump raised questions about the U.S. commitment to transatlanticism and NATO, and so the salience or necessity of the concept of EU ‘strategic autonomy.’ The UK vote to leave the EU (Brexit), also in 2016, freed the EU to increase the level of ambition with regards to its security and defense architecture. The European Union’s Global Strategy, adopted in October 2016, laid the ground for initiatives both in the framework of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the EU Defense Fund, while still focusing as a security provider in crisis management contexts rather than territorial defense. PESCO had been a possible instrument inside the EU since the Maastricht Treaty, but was not used until 2017. The EU’s focus on crisis management began in the late 1990s, when the then ESDP was created to react to crises in the EU’s neighborhood, not least the Western Balkans.

However, Russia’s invasion overturns our decades-long confidence that the European continent is safe from military aggression. That the EU itself was constructed around post-conflict economic cooperation between Germany and France – to Europeanize coal and steel as the resources of war - and partial political integration to foster good cooperative relations within and outside the EU, means Russia’s blood aggression fundamentally threatens EU identity, its standing as an ideal, its foundational principle (“never again”), and so its future. Putin’s fourth war in Europe (Chechnya 1999, Georgia 2008, Crimea and Donbas 2014, Ukraine 2022) further and unambiguously demonstrates that peace is not a given and that the apparently abstract and idealistic pillars of EU foreign policy are practical, useful, and can have real impact in real time.

Hardly surprisingly, the systemic shock and compounded crises engendered by President Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has a forcing function within the EU: the crucible of Russia’s “war of choice” identifies foundational questions. What capabilities are needed to be developed to undertake effective crisis management and be a security provider? How able is the EU to develop capabilities and partnerships to project resilience and stability in its immediate neighborhoods in the North, East, and South? Can a shared brand identity that can cross diverse policy fields (e.g., climate change, refugees, fiscal policy, Ukraine) be expressed differently in different national contexts? Can the EU strive for consistency and unity in addressing current and future challenges over the next 10-15 years, projecting resilience across its borders? What, then, ultimately, is the EU’s role to be within the current global order?

That the list of open questions is long is telling not just of the reality of complex cascading and compounded crises but also, more fundamentally, of a sense that the EU at heart lacks a clear raison d'être as a security provider, linked to rational priorities and giving hope for a future direction. The extent to which the EU can act has practical real-world implications: the EU’s ability to act will not only determine its role in the emerging global order but shape the nature of that order itself. The test case for the EU’s ability to act will be in responses to address and manage the various threats and challenges in its neighborhood, particularly against state-based aggression in the East and systemic and structural drivers of insecurity in the South.

Objectively, the EU has the capability and partnership prerequisites necessary to be a global power, including the necessary economic strength, soft power, and international presence. But the EU’s “Strategic Compass” (SC), adopted by the European Council on March 25, 2022, (particularly when viewed following Russia’s invasion and its aftermath) appears dull, technocratic, reactive and responding to internal challenges and external threats as they emerge, behind the curve, the product of a different paradigm.

The SC is the result of a two-year-long process of threat analysis and reflection undertaken by the EU regarding its foreign, security, and defense policies. As the EU plans to review its threat assessment in 2022, the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies organized a workshop to explore, assess, and stress-test the outlook as outlined in the EU’s SC. The Workshop was designed and structured to leverage the functional and national diversity of all participants to avoid “group think,” stress-test old ideas, and to generate new thinking. It identified the current and anticipated security threats in all three neighborhoods. To that end, three thematic working groups examined EU: 1) capability development and crisis management; 2) partnerships, and 3) narratives. Each day focused on specific sub-regions: the North; the East/Western Balkans; and the “South.” This iterative process allowed for reflections day-to-day, sub-region/theme to sub-region/theme, which resulted in an ability to synthesize and conclude. Conclusions identify considerations for the EU.

“The North”

Nordic states had prioritized predictability and stability in its relations with Russia. Russia’s mobilization of 100,000 Russian troops and multi-axis invasion after the questioning of Ukraine’s statehood and right to exist came as a profound shock. It shaped public attitudes and opinions in Finland (invoking in scale and imagery Finland’s “Winter War” 1939-40) and Sweden in favor of NATO membership, and in Denmark triggered a referendum to join CSDP. A strategic shift has occurred in the North, beginning with the mindsets in Finland and Sweden to move from armed non-alignment to alliance: the utility of NATO’s Art. 5 (collective defense) trumps the Treaty on EU’s Art. 42.7 (mutual defense clause) and Finnish-Swedish defense alliance. This thinking suggests that EU ‘strategic autonomy’ is not wedded to an understanding and that this is best achieved through a fully functioning cooperation of European armies to defend the EU against outside aggression. Although the accession process was unexpectedly “paused” by Turkish objections, raising the prospect that long delays may damage the credibility of NATO’s “open door” policy, on June 28th those objections were lifted – for now. The Kaliningrad “blockade” may be viewed by Russia as the opportunity to question Lithuania’s statehood. The defense of the Aland Islands and Gotland, Russia’s repeated airspace violations, the suspension of Nord Stream II, and cooperation with Russia with the Arctic Council are all challenges that effect this region.

With respect to the Arctic, the EU claims a more visible role since the adoption of policy guidelines in 2016. The EU projects international agency by promoting green policies to counter climate change, and it also acts as a legislator: European Union territory includes three out of eight Arctic States: Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. In the near future, seven out of eight Arctic States will also be NATO members. In addition, NATO is committed to increasing its rapid response force from 40,000 to 300,000, and this profound shift will have real impacts if such rearmament addresses the issue of sustainability (logistics, manpower, and training). The four European Forward Battle Groups in the Baltic states are set to move from battalion (1,000 troops) to brigade size (5,000 troops), creating a reinforced division that can act as more than a trip-wire and deter Russia.

- Capabilities and Crisis Management:

- The EU needs to develop capabilities to address threats and challenges in different domains, not least hybrid threats (cyber, disinformation, instrumentalization of minorities); resources (energy and food security); economic (industrial espionage, foreign investments), climate change (affects operational environment, natural disasters) and military threats (conventional and nuclear aggression, technological development). Building capability is challenged by differences in strategic culture and in operational environments, the securitization of external borders, a mismatch between budgets and expectations, and ambitions. The EU needs to further develop full spectrum forces that are agile and mobile, interoperable, technologically advanced, energy efficient, and resilient. Pooling and sharing, as well as a renewed focus on education, training, and planning can build a shared understanding. The EU can also ask: what capabilities are needed for contingencies short of Art. 42/7?

- Partnerships:

- The SC identifies “aggressors,” “competitors,” and “partners.” Russia is an aggressor (power politics) (SC, p. 5-7), using intimidation and threats to the sovereignty, stability, territorial integrity, and governance of “Eastern partners.” The EU participates in a competition of governance systems accompanied by a “real battle of narratives.” (SC, p. 5) China is identified as a partner for cooperation, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival. The United States is EU’s staunchest and most important strategic partner, contributing to peace, security, stability, and democracy on the continent. (SC, p. 8)

- The North is not an external priority for partnerships though third country cooperation occurs with Norway and Iceland through the European Economic Agreement (EEA) and PESCO, the UK through the Joint Expeditionary Force, and the United States is present in the region through NATO. The North does though, highlight the limits of EU foresight and false assumption: Russia does not play by the same rules as the EU. At the same time, the focus in the North should acknowledge that China also seeks to change the status quo in the North. While values and interests are encapsulated by the notion of a “Helsinki Spirit,” if the EU develops an understanding and consensus around the EU’s role and competencies and partnerships, a clearer understanding of EU’s direction is needed. Such clarity would also bring into focus opportunities for sectoral cooperation with the partner countries.

- Narratives:

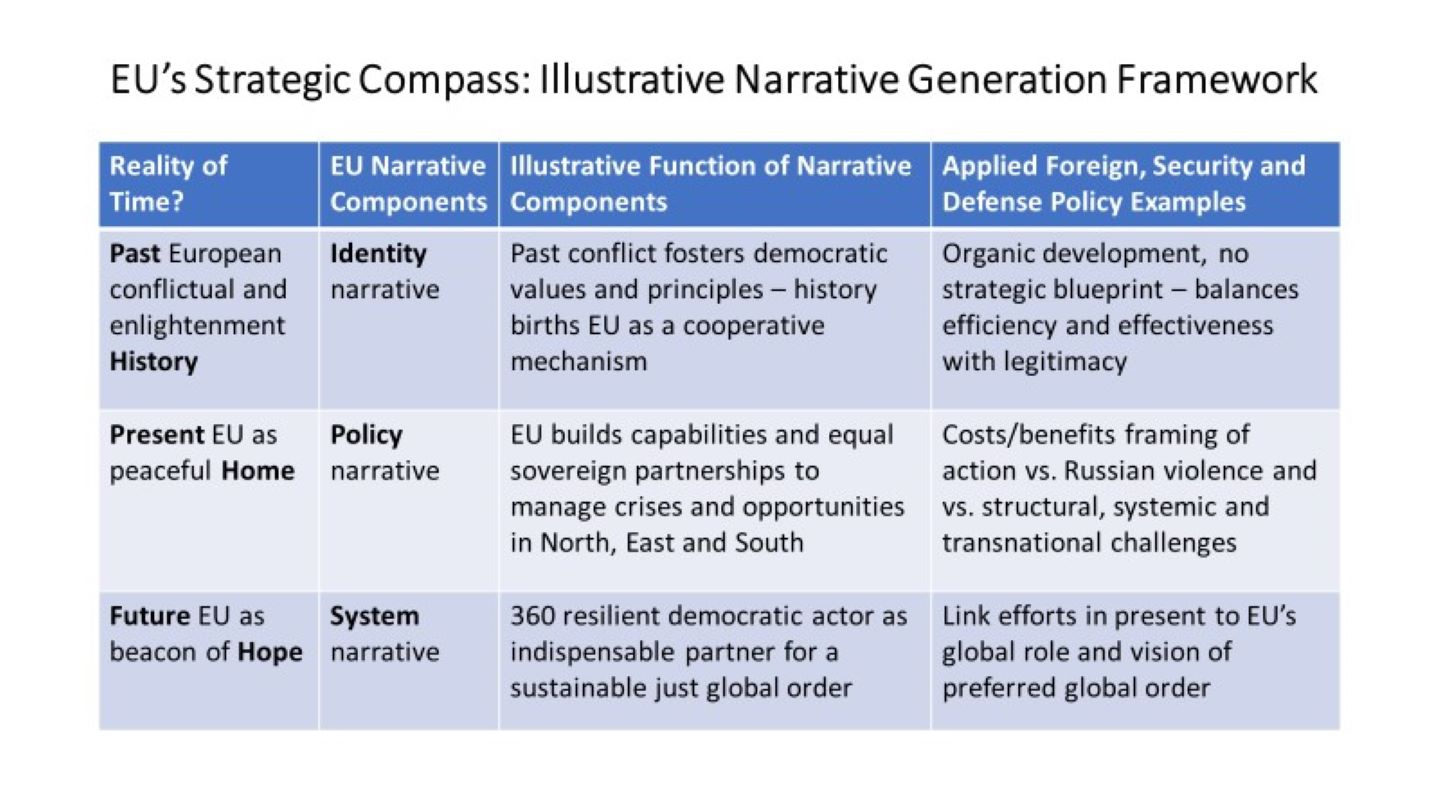

- “Narrative” is a neutral term. Narratives construct and shape our perceptions and memories. The purpose and function of narratives can include explanation to legitimize, garner support, maintain focus, increase resilience, and improve sustainability. Narrative can both foster cooperation or confrontation, depending on the willingness of the actors to align in constructing shared meaning or not, and should be considered more than media campaigns or frames. “Good narratives” are tailored to an audience, evoke emotions, are supported by coherent actions (strategic communication), and gain interpretive dominance. A political and strategic narrative constructs a shared meaning of the past, present, and future.

- Three types of interwoven narratives can be identified: 1) Identity narratives are narratives about an actor, the factors that constrain and define their actions, character and ideas, how the actors will behave in the future and who is considered friend, enemy, small power, great power, etc.; 2) Policy narratives advance normative or interest-based agendas; 3) System narratives focus on the economic or political systems actors inhabit, such as liberal world order, bi-polar order, and polycentric order.

- The core strategic vision proposition in the SC is that a stronger and more capable EU in defense and security contributes positively to the global rules-based international order with the United Nations at its core and transatlantic security as its focus. The EU, it is claimed, can protect its interests and defend its values through 1) being a single market and trade and investment partner and development assistance, 2) as a norm setter that is able to address the “normative void “ through shared values of peace, freedom, democracy, and rule of law; and, 3) as a leader in effective multilateral solutions, willing to take risks for peace and shoulder its share of global security responsibilities. (SC, p. 5)

“The East”/Western Balkans

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 has not gone according to President Putin’s plan. A multi-axis attack did not result in the seizure of the capital, “liberation” of the Ukrainian people from a “Nazi” regime, demilitarization, and then the incorporation of “Ukrainian Russia” into the newly minted empire. The Russian retreat from Kyiv and their reset to focus on expanding military occupation from Donbas to Kherson is a ‘work in progress.’ Extrapolating forward, it is possible to envisage three broad alternatives unfolding of the war, each alternative leading to different regimes in Russia, and each regime advancing different foreign policies. These outcomes suggest that the operating environment that faces the EU in the next 5-10 years with regards to the “Russia factor” includes Russia’s own implosion. These alternative futures have profound implications for EU capability acquisition, partnerships, and articulation of the narrative. Let us examine each alternative in turn.

The first alternative future can be called “Brezhnev 2.0.” It is predicated on a military stalemate and operational pause in July in which both sides attempt to bolster their logistics and resupply. By August and September, according to this future, it becomes apparent that Ukraine has the advantage and this is expressed in counter-offensives around Kharkiv and in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions. Tactical humiliations have strategic effect. In October Putin declares a Potemkin victory and Russian forces pull back to the February 23, 2022 borders. A coup is mounted in Russia, Putin is removed from power, and the Security Council brokers a successor transitional alliance. What does this alternative future assume about the functioning of the Russian system? First, if Russian military collapse in Ukraine leads to coup in Russia, then Putinism can exist without Putin – the regime is self-resilient not Putin dependent. Second, intra-elite bargaining would give regional elites a bigger voice, and a weak technocratic consensus candidate manager would emerge as President: Sobyanin as consensus candidate? Third, in foreign policy towards the West coexistence is still possible - gradual unwinding of UKR occupation; Russia in international system: predictable, pragmatic economic approaches (44% of GDP from foreign trade) – Russian military can still be funded. Lastly, such an outcome has elite support as it resonates with post-Putin predictive thinking: Soviet-type stability/stagnation and PRC dependency better than perestroika II, regime, and political system collapse?

What of the implications for the East and South East/Balkans? This alternative future best chimes with the aspirations expressed in the EU’s Strategic Compass. It builds on Ukraine and Moldova’s EU candidacy status (23-24 June EU summit) with a fast-track integration process and new “Marshall Plan.” The “European path” is validated in the Balkans with Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, Republic of North Macedonia, and Serbia looking to EU candidacy under the rubric of democratic resilience building. As part of this process states in the region integrate into CSDP missions and operations and the EU-led Pristina-Belgrade dialogue. However, Russia itself is destabilized, with the near inevitability of a third Chechen war, as Putin’s patronage ends and a fight over revenue flows unfolds. While Belarus remains independent, Russia’s legitimacy crisis impacts on the roles of its military bases in Tajikistan, Armenia and Moldova as an effective tool of foreign policy influence.

The second alternative future is characterized by vertical escalation. Here Russia responds to Ukrainian counter-offensives Kharkiv, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia regions through vertical escalation in the form of a tactical nuclear attack. This allows a military reset and a revitalized use of Russian military force which once again threatens Kyiv, Odesa, and Dnipro and forced “pacification” (camps, terror, deportations) occurs in the occupied territories. What does this alternative future assume about the functioning of the Russian system? First, Putin’s management is central to system and that those willing to remove him are unable; those able are unwilling. Vertical escalation triggers Russia’s isolation in the international system and forces a break with China and India. Second, a consolidation of elite and society occurs within a national security emergency regime, expressed by the idea: “We have passed the point of no return.” Slavophilism, Stalinism, anti-Western, anti-liberal thinking supports unambiguous confrontation with Euro-Atlantic space. Third, Putin’s predictive thinking that supports this outcome is based on the notion that it is better for Russia to be a “rogue DPRK” than a China-dependent “greater Kazakhstan with nuclear weapons.” “North Koreanization” is understood as a necessary means to preserve Russia’s strategic autonomy.

What of the implications for the East and South East/Balkans? This alternative future directly opposes the aspirations expressed in the EU’s Strategic Compass. Nuclear attack on Ukraine causes contamination and forced mass migration, as well as exacerbate food and energy crises. Belarus is reduced to Russian Federal District status and Russia imposes its hegemony on a “Eurasian Sparta.” Horizontal spillovers from Ukraine into Georgia, Moldova, and the Balkans in the shape of strategic intimidations, direct threats to statehood, and the triggering of new wars, alongside increased “guerilla geopolitics” – that is, subversion and political warfare.

The third alternative future can be understood as “Brezhnev-DPRK.” It is predicated on a shift of the conflict from protracted to frozen, with no vertical escalation or full mobilization in Russia. Ukraine is too strong militarily to be defeated in the field, but not strong enough to mount counter-offensives. Russia digs in and attempts to turn military occupation into political control with the foundation of Kherson People’s Republic (KhPR), Zaporizhzhia People’s Republic (ZaPR), to match the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) and Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR). These so-called People’s Republics are then annexed into Russia as Federal District and placed under Russia’s nuclear umbrella.

What does this alternative future assume about the functioning of the Russian system? First, that Russia lacks the military capability and will to end its “war of choice” on favorable terms but is unwilling to accept greater risks (full mobilization) that might allow “victory.” Second, because Russia does not use nuclear weapons, the Russia-China axis is still viable, and Western sanctions promote Russia’s strategic reorientation eastwards and to the Global South. Third, Putin’s “theory of victory” is based on the net effects of the deliberate systematic destruction of Ukraine’s critical national infrastructure (CNI) and economic base (through systematic missile attacks and a maritime blockade). In addition, Putin will predict that western unity will break and in a zero or negative sum context, Russia’s pain threshold is greater.

What of the implications for the East and South East/Balkans of a frozen conflict in Ukraine? Such an outcome would prevent Ukraine’s stabilization, though while Ukraine’s EU candidacy would become “prolonged,” its diaspora in the EU would grow and at the citizen level integrate into the EU. Russia would assert the “Putin doctrine” in the “near abroad,” marked by the annexation of Belarus, more Baltic provocations, the use of strategic intimidation, subversion, and political warfare to destabilize the Balkans and prevent EU integration.

Currently, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine creates a policy trilemma for the political West that seeks three objectives but may only be able to achieve two. What are these objectives? First, to provide Ukraine military arms, training, and actionable intelligence to maintain statehood in order to give Ukraine greater leverage to create a more sustainable peace. Second, to balance pragmatic national interests with democratic principles. Third, the political West maintains a degree of ambiguity over the desired end state. This is designed to uphold unity, avoid unwanted escalation and the West becoming a “party to war,” limit open-ended commitments to Ukraine, and maintain potential “offramps” for Russia.

- Capabilities and Crisis Management:

- The Ukraine invasion has promoted a sense of solidarity in the EU and convergence in perception of Russia as the aggressor and has identified more clearly the practical consequences of capability shortfalls and utility of Dialogue Forums. In terms of external challenges, Russia’s asserted sphere of influence is very much in evidence, and though less visible, other spheres of external influence (China, Turkey) are also apparent. The challenge for the EU is to assert its relevance and maintain the credibility of the integration process and cohesion. Internally, the EU needs to focus on activating its capability development initiatives, utilizing its dialogues, strategic documents, and reassurance measures.

- In the external sphere, the EU can utilize a range of tools, from economic sanctions against Russia and economic support for Ukraine, to activating the European Peace Facility, its rapid deployment capacity, CSDP operations, EUFOR, EULEX, and the Eastern Partnership. However, the plethora of instruments and tools needs to be matched by the political will to make decisions to use them. This approach needs to be supported by STRATCOM (strategic communication) for the EU’s internal and external audience.

- Partnership:

- The EU adopts a differentiated approach to the Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries (Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan), the Republic of Turkey, and the Western Balkans. The EU’s former core partner in the east – Russia – effectively seeks to undermine and destroy the EU itself. This shared threat creates a cooperative and unifying imperative with the EU.

- The EU’s ability to act not only stands and falls with the political will of its member states, but with its skill to manage perceptions and expectations both internally and with its neighbors. In this regard, tensions are also apparent. With the offer of candidacy status to Ukraine and Moldova, the tension within the EU between widening or deepening will come to the fore, as will questions associated with the debate between advancing new formats of partnerships vs. enlargement.

- Russia and China’s role in the region is a core challenge to EU partnership policy. Additional tension arises from the inconsistency of the EU’s handling of non- or illiberal democracies, both internally and externally. Multiple crises that need to be managed simultaneously stress test the ability of the EU and NATO to act in complimentary, not competitive, ways and put the spotlight on the meaning of EU strategic autonomy. Tailored partnerships based on cross-sectoral cooperation and a principled pragmatic approach can address some of the gaps and shortfalls associated with partnerships in an age of disruption and conflict.

- Narratives:

- Russian aggression in the East drives a compelling narrative around solidarity, legality, ending aggression, and restoring order. The EU posits itself as engaged in democratic security building and striving to enhance democratic resilience to strengthen its being as stable, predictable, rule-of-law based, and adaptable. A dictatorial Russia provides a stark governance contrast and its aggressive illegal strategic behavior allows for a common threat perception and creates unity in opposing the weaponization of energy, food, and humanitarian aid supply chains and migration, even if honest policy differences exist in determining how best to do this. Russia, alongside China, also propagates an alternative competing narrative challenge to the EU. Both countries advance identity, policy, and systems narratives. Their narratives argue that Russia and China are aligned and promote prosperity and stability, while the United States and its European allies are to blame for turbulence in international system. Both degrade democracy, the rule of law, freedom, and human rights as tools of Western interest and influence. Russia actively strives to destroy the Western, rule-based system. It rejects the 1990 ‘Charter of Paris for a New Europe’ as an essentially anti-Russian project. Unlike China, Russia lacks its own compelling vision of the future, a developmental or modernization paradigm. Understanding the linkages between Russian and Chinese narratives helps develop resilient democratic counter narratives. If we are facing a “battle of narratives,” what would be possible approaches for the EU to prevail (e.g. “counter” or “take initiative”)?

- The EU was created as a fundamentally cooperative mechanism. However, the EU does acknowledge the existence of malign and confrontational actors, and recognizes the need to address this radicalized confrontational paradigm. Confrontation needs to be overcome. An EU narrative can directly confront the actions of Putin, but still express the desire to engage with Russian civil society (what will be the post-Putin generation), even if the message is blocked or instrumentalized by Russia. The EU needs to be adaptable as it lacks the means to influence and shape Russian strategic behavior, in narrative terms at least, due to Russian media control, information blockade and censorship. This suggests that the EU narrative should primarily connect with its own population and audiences in third parties, bringing focus and testing the proposition that less is more.

- The EU’s narrative needs to make explicit the link between its identity, its values, and its interests. The EU’s values derive from its identity and the practice of these values are the means to achieve EU interests. In practical terms, this entails accepting the tolerance paradox. Karl Popper noted that there is an inherent internal tension in democratic societies between the liberal expression of dissent and the acceptance of opinions not completely allied with our values, or the exaggeration of the principle of liberty (everyone has unbridled freedom to make of this what they want) and stability. In open, democratic, liberal societies, conflict of opinions and disagreements are allowed. Even though this may be a source of instability, instability is constitutive of democracy. Moreover, democracies and liberal societies have in themselves the instruments to manage (and tolerate) this instability (e.g. voting, checks and balances, separation of powers, education). Externally the tolerance paradox finds expression in accepting that partners, neighbors, and competitors have the right to choose their own strategic orientation. But there are limits to the choices – Russia’s “war of choice” in Ukraine breaches what is tolerable. As a result, the EU’s most urgent task is to maintain continental peace and security, through to the east.

“The South”

The South faces multiple threats. In a hard power perspective Russia’s military support for Syria, a client regime on the verge of collapse in September 2015, marks a shift for the strategic environment of the entire Mediterranean space. Russia filled the void left by the United States and its control of military infrastructure in Syria (Tartus, and air bases) places UK base in Cyprus and U.S. Incirlik in Turkey within strike distance of Russian missiles. In February 2022, the deployment of hypersonic missiles with a 2,000 km range covers South East Europe. Tartus was also used to provision Baltic and Northern Fleet vessels heading for the Black Sea to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Syria acts as a stepping stone to Jufra, a Russian base in Libya, and allows further power projection into CAR and Mali. The image of Russia and the compatibility of “bad governance” norms are attractive to authoritarian regimes. Following a military coup in Mali, Russia’s Wagner Group was invited to partner the junta. The prolonged deadlock and political-security vacuum in Libya suit Russian interest. From Jufra airbase, Russia could deploy long-range missiles that threaten Europe. Russia can also weaponize refugee flows, organized criminal (human trafficking), and violent political extremist networks. While such illicit activities have multiple causes, prolonged civil wars in Syria and Libya are certainly key drivers.

Russian gas exploration in northern Iraq, Lebanon, and Egypt also provide a means of presence and influence. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has impacted fertilizer and food supply chains, changed financial flows into Cyprus and Turkey, and disrupted air and sea traffic. In short, Russian actions have degraded the rule of law, created political instability and increased risk for both the EU and the South.

Turkey’s role in the region is a destabilizing factor. Russia was able to use the sale of S-400’s to Turkey to exclude Turkey from F35 sales, and such splits between NATO members create a strategic advantage for Russia. Turkey no longer supports a “comprehensive settlement” in Cyprus, but now advocates for a “two state solution.” Turkish definitions of regional borders differ from those of Greece. President Erdogan is focused tactically on winning the ballot box, rather than a vision for Turkey. Erdogan can channel underlying Turkish nationalist settlement, and any post-Erdogan president will need to reflect this reality. Elections in 2023 have symbolic importance for Erdogan, in that he will surpass Ataturk’s time in power (even as he destroys Ataturk’s legacy) and October 2023 marks the centenary of the republic, the crowning of Erdogan’s political career.

Apart from Russia and Turkey as regional and international actors in the South (not least China), Europe’s Southern neighborhood bears a whole range of structural challenges, especially socio-economic and ecological threats. The combination of demographic pressure and climate change results in an aggravation of the water-energy-food nexus and increases the need or motivation to migrate. Political instability and high unemployment rates in most North African and Middle Eastern countries are driving young people to leave in search for better life chances. Terrorism and transnational organized crime are chronic problems.

- Capabilities and Crisis Management:

- As with other sub-regions addressed above, threat perceptions drive the procurement of capabilities, defining what is necessary, as well as when and where. A shared strategic culture defines attitudes towards the use of force and generates the norms that justify its use. A consensus around the EU’s role and competencies enables action. EU instruments for the South include: Funding Assistance (“More for More”) within the European Neighborhood Policy, economic sanctions and embargoes, CSDP Operations and EU Training Missions and Operations, financial support to UN Operations, Maritime Coordinated Presences, FRONTEX, EUROPOL, and the Single Intelligence and Analysis Capacity (SIAC).

- In “the South,” the lack of EU cultural awareness (the importance of the local ownership principle in post-colonial contexts) is a weakness. Legal constraints placed on operational mandates impact force generation and so strategic outcomes. Looking to the future, the invocation of Article 44 (‘Coalitions of the Willing’) could sharpen focus and lead to more effective and efficient outcomes.

- Partnerships:

- The strategic context in the South is characterized by ecological-climate, socio-economic, and demographic pressures that are evident in water-energy-food scarcity, limited access to education, unemployment, and inequality overshadowed by the mirage of authoritarian stability. Global systemic factors are particularly apparent and climate change exacerbates all of it and is a driver of instability. In this sub-region national interests of partners clash more starkly with EU interests, and the EU’s tool box is more limited – EU membership, for example, is not on offer as a shared future goal. In this region the EU must navigate many fault lines, not least those between Morocco and Algeria, Saudi Arabia and Iran, and Israel/Palestine and the competing narratives these conflicts generate. States in the region may maintain balancing acts between the EU/Ukraine and Russia. The EU has a history of over-promising or underdelivering and partner ‘absorption capacity’ issues (Jordan and Lebanon as examples) can be securitized, and the issue of migration and refugees (double standards) weaponized.

- In such a diverse southern context, a differentiated approach based on tailored partnerships is most appropriate, acceptable, and affordable from the perspective of states in the region. As “the South” will be critical in replacing “the East” in efforts to diversify energy supplies, including renewable energy, the EU must prioritize areas of cooperation with the best chance of success, including increased investments in connectivity to drive regional trade and commerce, a focus on state resilience but not at the expense of neglecting societal resilience, further investments in education and training (i.e. expand the ERASMUS program), and projects to mitigate climate change and increase energy connectivity are priorities. This neighbourhood lends itself to the integrated approach (economic–security–political) and this in turn promotes the EU’s role in mediation (JCPOA/Libya/Palestine-Israel/Eastern Mediterranean). The EU should expand cooperation with existing multilateral frameworks (e.g. OSCE Med Partnership, Union for Mediterranean) and, as with “the East,” reinforce its diplomatic actions to build coalitions where it needs coalitions and highlight the fact that such coalitions illustrate the validity of its own adaptable model.

- Narratives:

- As with the East, the EU needs a clear narrative about its relationship with partner countries. The narrative challenge in the South revolves around the relationship between colonial and post-colonial states. If the EU’s objective in the South is not ultimately, EU membership, what is it? The notion of “equal partnership” based on good governance (not explicitly Westernization or democratization) and sectoral integration where appropriate appears sensible. This entails an understanding of the costs and benefits that may even out only through time (diffuse reciprocity) and that a shared history (“longue durée”) and geography allows for such a non-transactional approach. Confrontation-based narrative of colonialism which focus on colonial versus post-colonial states can/should be answered or at least tempered by a “Mediterranean narrative” stressing the role of the Mediterranean Sea as a trading, economic, and cultural bridging geography, linking different peoples around the Mediterranean basin.

- The EU can engage with the North African and Levant diasporas within its borders and provide educational opportunities as a soft power tool. EU values, including respect for human rights and the rule of law, are part of that appeal, but also the ‘right to choose.’ In this perspective individual states can differentiate their engagement with the EU according to what is acceptable to their societal values, affordable, and appropriate to their strategic contexts. The EU reciprocates. Tailored partnerships have their place.

Synthetic Summary

The EU’s SC represented a big leap forward in terms of the expression of principles. However, it was Russia’s shocking invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that created the catalyst for policy advancement, including decisions around sanctions against Russia, the supply of weapons against Ukraine, and the use of enlargement policy. The EU uses power in a new way, combining economic and military tools, creating a complimentary approach between the EU and NATO, and in June 2022 the European Council offered EU candidacy to Moldova and Ukraine. The EU challenges Russia’s brand of governance and its ability to exert power. Russia’s brand finds some support amongst states in the Global South. In general terms, 40% of the world’s 193 UN members vote with the EU in the UN General Assembly, the rest sit on the fence, and a few support Russia.

To build on the existing galaxy of capabilities and tools for effective EU action and to act with the support of capable partners, the EU must explain to the EU itself (civil society, political elites) and partner states and societies its goals, what it wants to achieve, how and why. It must tell a compelling story. The policy approaches adopted by the EU should be supported by coherent actions that resonate with EU values and achieve its interests. In this way the narrative will be authentic, gather support, help maintain focus, demonstrate resilience, and be sustainable.

In this respect, challenges to EU’s ability to act can be acknowledged, including: tensions between individual EU member state’s threat perception and common interests, soft and hard power, supra-national and intergovernmental approaches, solidarity and transactional interests, the logic of efficiency versus legitimacy that comes from integration and cohesion, and the tensions between unity and diversity. Article 44 (the use of EU coalitions of the willing) and a shift in mindset and geopolitical thinking should be reflected in internal and external EU narratives.

In constructing a narrative, fear is a factor, both positive and negative. Too much fear of challenges and threats can lead to policy paralysis. Demonizing the adversary can be dehumanizing and undercut shared values and perpetuate cycles of conflict. But fear of failure can also sharpen and refine wisdom. While a narrative does not have to be rooted in reality, it will inevitably and in time be checked by reality. A strong narrative provides the story that justifies action, but these broad principles can be applied, connected with, and be expressed according to what is acceptable, affordable, and appropriate at the local context.

The internal goal of the EU’s narrative is to communicate an EU “grand vision” around Europeans’ common interests and values. To increase public awareness and make the narrative connect with the lives of EU citizens, cost-benefit frames expressed in everyday language can be used. The external goal of an EU narrative should be to communicate to all external partners and actors its determination to use power in support of its values. Attention can be paid to the power of tailored language and the narrative can be evidenced differently in different regions according to what is appropriate given differing strategic contexts and priorities, acceptable given differing societal values, and affordable. The East responds well to a narrative that focuses on military support and the prospect of rebuilding; the South is sensitive to perceptions of neocolonialism and receptive to approaches based on equal partnership and prosperity. The same need for tailored language (and narrative) applies also inside Europe: the need to address the different peoples of EU through a language fitting the respective sensibilities, needs, and expectations.

Three narrative propositions can be advanced. First, the EU is best structured to address transnational issues, the threat of and actual inter-state violence, and global systemic challenges. As interdependence, transnationalism, and globalization are central feature of the international system, the EU born as a cooperative mechanism (designed at conception to Europeanize the weapons of war – coal, steel, nuclear) is best placed to tackle this agenda. Second, because the EU holds itself accountable to its past marked by civilizational advances but also by conflict and confrontation, it can be responsible for its future. European history is a history of intolerance, colonial imperial outreach, and continental-scale warfare. It is also a history of mutual meetings, emancipation, development, culture, and hard work for equality. In this sense, learning from mistakes and the willingness and capacity to overcome them is a competitive advantage. It can help us shape the future. Third, crises have catalytic effects on EU action, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated. The EU can adapt in the face of systemic shocks, and does so at speed.

Looking to the future, partnership goals include diversifying energy supplies to decrease dependence on supplies from any given actor, especially Russia (“blood money” being the operative phrase). The EU’s green energy policy allows the EU to be true to its ideals, to build resilience, and to achieve practical geopolitical outcomes. In narrative terms, we see a shift from coming to terms with violent national pasts to focusing jointly to create a pathway for the new generation to live at peace in a future they desire. The EU’s increasing investments in connectivity to drive regional trade and commerce (Global Gateway and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment) is a core part of this future agenda. EU cooperation allows member states to “make globalization safe again” by collectively benchmarking higher standards for the environment, food safety, public health, and social justice. The EU becomes a more attractive model as it can stand aside from the global race to the bottom. The matrix below provides an indicative framework for the generation of tailored EU narratives to manage threats, crises, and opportunities through building capabilities and partnerships in the North, the East/Western Balkans, and the South.

About the Authors

Dr. Graeme P. Herd is a Professor of Transnational Security Studies and Chair of the Research and Policy Analysis Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (GCMC). Dr. Herd runs a monthly Seminar Series which focuses on Russian crisis behavior, the Russia-China nexus, and its the implications for the United States, Germany, friends, and allies. Prior to joining the Marshall Center, he was the Professor of International Relations and founding Director of the School of Government, and Associate Dean, Faculty of Business, University of Plymouth, UK (2013-14). Dr. Herd has published eleven books, written over seventy academic papers and delivered over 100 academic and policy-related presentations in forty-six countries.

Dr. Katrin Bastian is a Lecturer of Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. Before joining the Marshall Center in autumn 2020, Dr. Bastian worked as the personal adviser to the Ambassador of the Principality of Liechtenstein in Berlin. During her sixteen years of service at the embassy, she also worked as lecturer of international relations and EU foreign policy at Humboldt University Berlin (2005-2008) and at the University of California at Berkeley (2009).

Lieutenant Colonel Falk Tettweiler works in the Research and Policy Analysis Department of the College of International and Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. He has extensive expertise in European and German Security Policy, which he gained during his work in the German Federal Ministry of Defense, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), and the Federal Academy for Security Policy (BAKS). Lt. Col. Tettweiler has served on Active Duty in the Germany Army since July of 1994.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany is a German-American partnership and trusted global network promoting common values and advancing collaborative geostrategic solutions. The Marshall Center’s mission to educate, engage, and empower security partners to collectively affect regional, transnational, and global challenges is achieved through programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 15,000 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

Marshall Center Perspectives are short papers that document lessons learned, offer new insights, and present policy recommendations that have been developed in collaboration with our resident course and outreach event participants as well as our alumni.

This summary reflects the views of the authors (Graeme P. Herd, Katrin Bastian and Falk Tettweiler) and is not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments. The authors gratefully acknowledge very helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this paper from Elena Alessiato and Vasileios Floros.