Russia and China Trade and Technology Dependence?

Introduction

How might we understand the term ‘economic dependence’ when applied to trade flows and technical cooperation between two states? Economic and technological links turn into dependencies when the link becomes difficult to replace and too powerful to lose, given resultant political tensions and pressure. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches can highlight the existence of dependencies. Quantitative factors include the size of trade and investment, labor migration and tourism. Dependencies can be analyzed and understood using statistical data and economic models. Dependency mitigation strategies can include the use of central bank reserves to replace export revenues if needs be e.g. if a downturn in exports of gas to the Chinese market. Qualitative approaches, by contrast, are less transparent and dependencies in technologies, key resources and critical infrastructure much harder to fully understand using statistical and trade data. Instead, academics, analysts and governments use anecdotal evidence, scenarios and foresight to uncover how deep the dependencies go. Mitigation strategies center on import substitution, but this can be difficult. Trade and technology cooperation is an important indicator of the nature, scope, and future trajectory of overall Sino–Russian relations.

Bilateral Trade

Russian trade with China increased in mid-2000. Bilateral trade was shaped predominantly by economic factors, contracting after the global financial crisis of 2009 and a drop in oil prices in 2014 that coincided with the annexation of Crimea and sanctions on Russia. 2021 represented a record year, as by the third quarter trade reached the levels of 2019, the pre-pandemic high. China’s share in Russia’s foreign trade stood at 2-3% of total trade in 1996, moving to 20-25% by 2021. However, from China’s perspective Russia’s share of China’s total trade has remained static, indicating while trade is deepening, it is one sided.

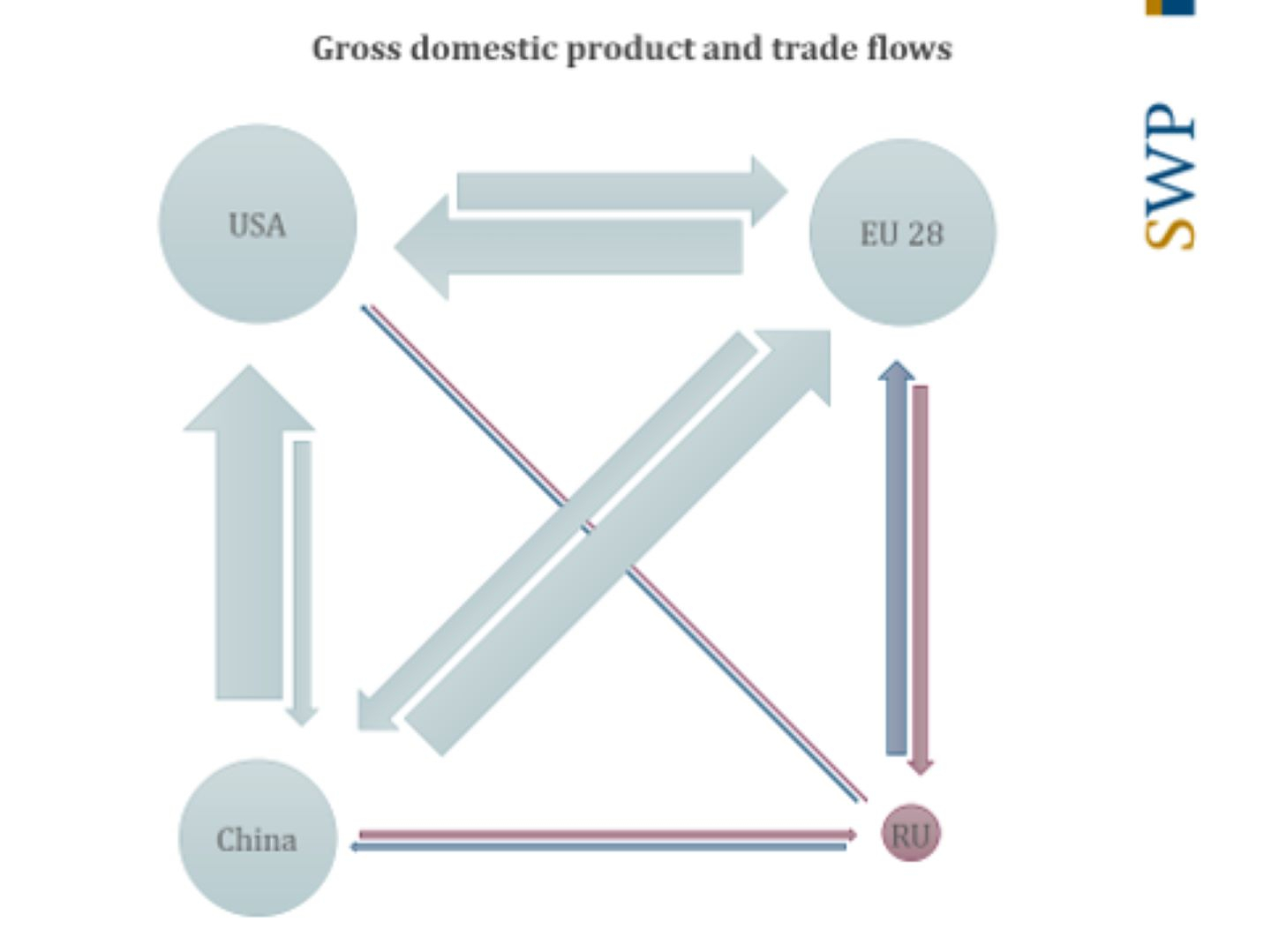

Moreover, quantitative data demonstrates the nature of trade flows between the US, EU 28, China and Russia. The slide above illustrates the relative size of GDPs (represented by size of circles) and trade flows (indicated by size of arrows). It is very clear that Russia is the economic outlier when compared to the three other blocs, with an economy the size of Spain or Italy. For both China and Russia, their economic relations with the West are much greater than bilateral flows between each other. As a result, China, for example, broadly respects Western sanctions in its trade relations with Russia. When we do focus on qualitative nature of the Sino-Russian trade, it is clear that Russia continues its commodity export model, indicating stagnation, while China moves to export higher value added goods, reflecting economic advancement. The expansion of overall bilateral trade and economic cooperative relations is primarily shaped by the profit principle, complementariness and mutual commercial gains.

Technology

Technological cooperation between Russia and China increased in the mid-2010s, but can be characterized as sporadic and focused on a small number of projects in arms technology, nuclear power and space exploration until 2018 when the US sanctioned China (Huawei). Sino–Russian emerging technology cooperation increases in more sensitive regarding collaboration in more strategic technologies, such as AI, information and communication technology (ICT), cyberspace and aerospace engineering, along with advanced military-technical cooperation. Already in the 1990s, there was cooperation around space exploration, but efforts to build a wide-body aircraft (CR-929) and an Advanced Heavy Lift Helicopter came only in the 2010s.

China focuses on common science and university research projects with Russia. Sino-Russian research teams published 1500 papers in 2015, 3000 by 2019. However, collaborative technological links with the West are much stronger: Russia-German research teams, for example, published 5000 research papers in 2019. Technological research and development is one area where Russia still has certain advantages over China (particularly in aerospace engineering, arms and nuclear sectors) and Russian official strategy seeks to safeguard this advancement, shaping the nature of its collaboration with China. One Russian cause of concern is Chinese firms hiring Russian IT specialists at higher wages to work in Russia, so depriving Russian companies of home-grown talent, representing ‘a brain-drain with Chinese characteristics.’ From a Russian perspective potential Chinese FDI in the technology sector raised the greatest hope but least results, though FDI admittedly hard to measure if it is delivered through conduit countries or firms (e.g. Cyprus).

Intensified strategic competition with the United States, its friends and allies promotes bilateral cooperation to counter-balance Western pressure and policies. Advanced arms trade and military-technical cooperation suggests future ambitions to promote collaboration in such areas as hypersonic technology, the construction of nuclear submarines, and strategic missile defense. If both Russia and China integrate their air and early warning missile attack systems and jointly share data and information about third-party launches. Russia would warn the Chinese about incoming missiles strikes, especially ICBMs, from stations in Russia’s north; and China would similarly warn the Russians via Chinese stations in China’s south and southeast. Another a key incentive for “authoritarian collaboration” is provided by the need to strengthen regime security, reflected in facial recognition technologies and a focus on Internet governance and control. In this respect, considerations that shape technological cooperation are less profit driven and more ‘political.’

Sanctions

Post-Crimea 2014 Western sanctions do not provide a compelling explanation of Russia’s pivot to China given Russia pivoted after the global financial crisis in 2009 (when Russia’s GDP contracted by 8%) to avoid overdependence on the West and to catch China’s economic wind in Russia’s sails, to use Putin’s phrase. Western sanctions caused Chinese businesses, such as banks, to sever links with Russia, reflecting the reality that Western markets are more important to China than Russia’s. Potential future Western sanctions of Russia could focus on Russian government bonds and state companies, with RUSAL’s experience an object lesson, causing pain for Western economies, but much more for Russia’s, and likely to scare off China, as before.

Were a hard decoupling of international supply chains to occur between the West and China, to what extent might China use Russian markets to mitigate its effects, given that Russia is politically aligned with China, but economically with the West? As Russian-Chinese bilateral relations best develop in a stable international environment the potential disruption of hard decoupling would not benefit the Russian economy nor compensate China for the disruption to Western exports: discretionary spending is low in Russia following ten years of falling living standards and the Russian market is small and already saturated with Chinese goods. Russian oil infrastructure (pipelines) is a lesser concern for economic dependency, as the oil market is much more flexible and return on investment much quicker in oil rather than gas pipelines, for example. In addition, China can increase gas supplies from Turkmenistan and LNG deliveries to compensate for Russian potential supply shortfall.

The read ahead for GPCSS#3: Christopher Weidacher Hsiung, “China’s Technology Cooperation with Russia: Geopolitics, Economics, and Regime Security,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2021, 447–479.

GCMC, December 1, 2021.

About the Author

Dr. Janis Kluge is a Senior Associate at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in Berlin; the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. His focus is on economic development and trade in Eastern Europe and Eurasia, Russian state budget, sanctions, and Russian domestic politics. He also serves as a Core Group member of the Marshall Center’s Great Power Competition Seminar Series (GPCSS).

Dr. Graeme P. Herd is a Professor of Transnational Security Studies and Chair of the Research and Policy Analysis Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (GCMC). Dr. Herd runs a monthly Seminar Series which focuses on Russian crisis behavior, the Russia-China nexus, and its the implications for the United States, Germany, friends and allies. Prior to joining the Marshall Center, he was the Professor of International Relations and founding Director of the School of Government, and Associate Dean, Faculty of Business, University of Plymouth, UK (2013-14). Dr. Herd has published eleven books, written over 70 academic papers and delivered over 100 academic and policy-related presentations in 46 countries.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany is a German-American partnership and trusted global network promoting common values and advancing collaborative geostrategic solutions. The Marshall Center’s mission to educate, engage, and empower security partners to collectively affect regional, transnational, and global challenges is achieved through programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 15,000 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in this seminar series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.