Russia End State: Current Paradigm and Alternative Futures?

Introduction

This first monthly virtual seminar for FY24 aims to provide a series of claims about the role of structure and agency in Russia, explore the rhetoric and reality of Russian foreign policy, and offer a typology that characterizes alternative power transition/succession future scenarios (highlighting their embedded assumptions) based on current trends and possible future dynamics. This set of ideas and arguments will act as a benchmark and then be challenged, amended, replaced with a clearer understanding, or supported and strengthened by further empirical evidence as the year progresses. What is clear is that there is little consensus among subject matter experts on many of the issues. We will have the opportunity for more acute analysis over 11 additional virtual monthly seminars (with the possibility of up to six drop-in seminars to respond to fast changing events) and two SCSS Workshops to explore these ideas further.

Structure, Regime, and Agency

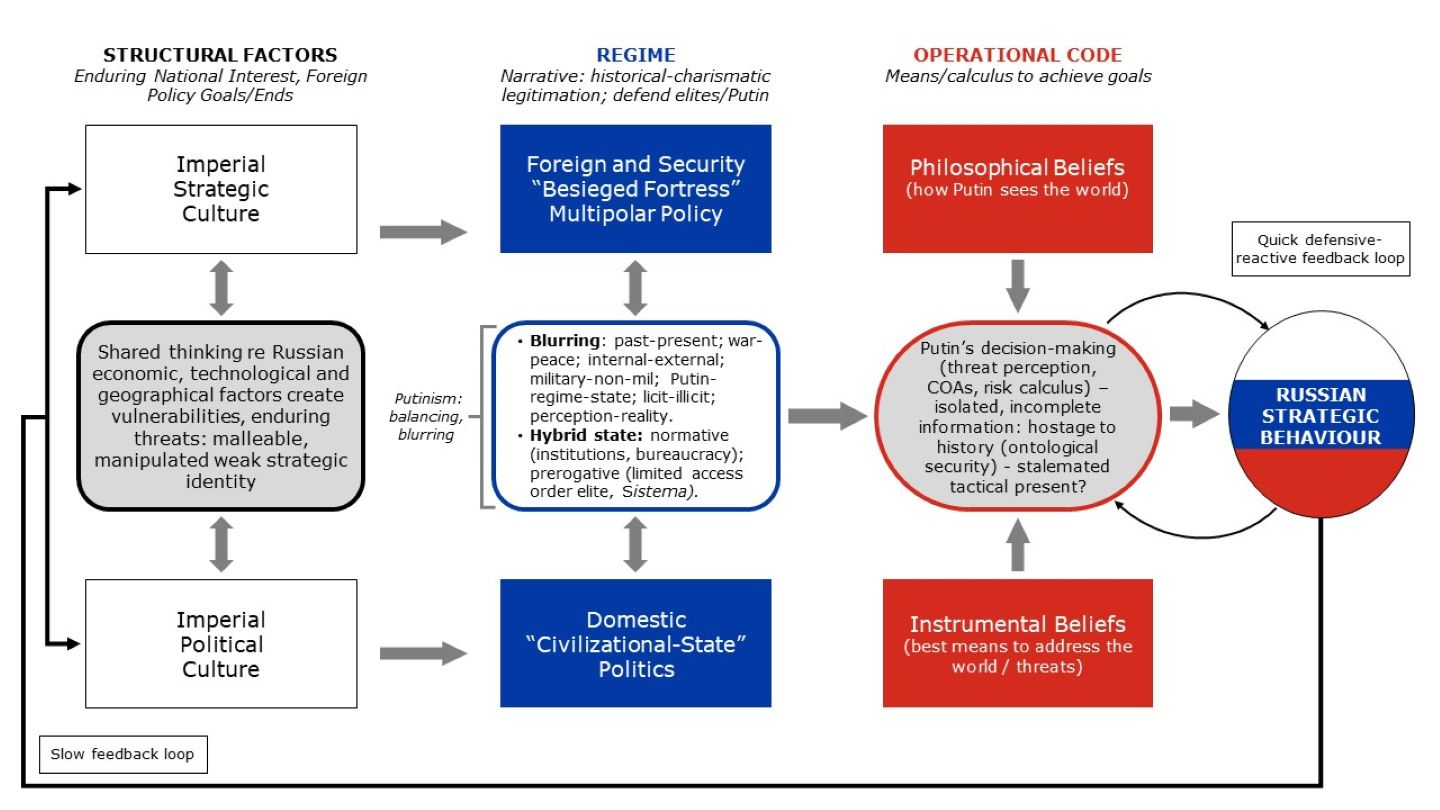

How Russian elites have historically viewed the importance and function of geography, technology, and the economy in creating and addressing threats and vulnerabilities is shown in the chart below, “Russian Structural Factors, Current Regime, and Putin’s Operational Code.” Russian elites shared a broad sense of legitimate and necessary responses to threats (strategic culture) and different regimes were able to create and propagate broad national interest based on their particular reading of the past. Structure, then, mediated by regime narratives, creates a broad consensus as to enduring national interest and broad foreign policy and security goals.

Regimes in Russia-controlled state institutions, including the media, education system, and Russian Orthodox Church, propagate nationalist-imperialist narratives. These narratives revolve around themes of ‘encirclement’ and Russia as a ‘besieged fortress,’ depicting external enemies as coveting Russia’s resources and fearing its military might. An imperial political culture views Russians as the system forming people and Russia itself as a “civilizational-state” (“Fundamentals of State Policy for the Preservation and Strengthening of Traditional Russian Spiritual and Moral Values,” November 2022, updated 2023). The regime promotes the sacralization of a strong, stable state and celebrates Russia’s unified “millennial historical path of Russia” narrative, but regime stability is upheld by a set of authoritarian practices (e.g. clientelism, electoral ballot stuffing, opposition persecution).

Tsarist, Soviet, and post-Soviet regime leaderships had some agency – they could exercise risk calculus, weigh different courses of action, and select different means to achieve such goals. The operational codes of different sets of decision-makers, that is, their philosophical (how they see the world) and instrumental beliefs (on that basis, what is the best response) explains why different leaderships exercise different choices. For example, all want influence in Ukraine: Yeltsin recognizes its independence in 1991; Putin orders full scale multi-axis attack on February 24, 2022. Different leaders can choose different means to achieve the same ends.

Putin’s regime (leadership) can be viewed in terms of a “limited access order,” that is, as an enclosed prerogative state elite that understands and upholds the “rules of the club” and benefits from access to revenue flows and Sistema. Putinism at home is ultimately defined by its lack of clarity. Its most visible characteristic is the blurring – of past and present, war and peace, internal and external threats, military and non-military tools, the merging of Putin-regime-state, and perception and reality. Putin deliberately does not offer a policy map or blueprint for the future. Putin avoids ideological certainty in order to maintain room to maneuver and to have strategic autonomy as a leader. Ambiguity, blurring, and balancing allow for unpredictability and strategic surprise.

In foreign policy, though, Russia’s narrative is structured around problem, blame, and solution – the core components of every ideology. Putin defines his full-scale invasion of Ukraine as a “Special Military Operation” not a real “war.” In fact, according to this understanding, Russia fights the West in Ukraine, and as such Ukraine is the first battle in a wider global struggle. As Putin stated at the Valdai Club meeting on October 5, 2023: the “Ukrainian crisis is not a territorial conflict. The issue is broader and more fundamental — we are talking about the principles the new world order will be based upon.” The militantly liberal totalitarian West (“Anglo--Saxons”) seek to unjustly uphold unipolarity through colonial unequal practices. This current order, Russia asserts, poses an existential threat to Russia’s identity and sovereignty. The solution, or victory in this global struggle, is the “inevitable” emergence of “fair multipolarity,” an “unstoppable process,” according to Lavrov, and one that Russia supports. Russia targets its “lets fight Western imperialism” and oppose U.S. hegemony narratives towards the” hedging middle” in the Global South.

In reality, Russia’s vision for a global order appears to be the “Vienna” European Great Power system projected onto the world stage. This suggests that “fair multipolarity” norms will include “super-sovereignty” (“some states [Great Powers] are more sovereign than others”), which allows Russia to act as a rule shaper and rule breaker. Russia as a “state-civilization” – an undoubted euphemism for “empire,” seeks to “make the international system safe for emerging empires.” For Russia, as the United States is a superpower and breaks the rules, it follows to break the rules is a hallmark of a superpower, not to break the rules is to become “Greater Kazakhstan with nuclear weapons,” that is, strategically irrelevant. Russia’s foreign policy is value-free, bilateral, interest-based, highly pragmatic, transactional, and situational. In Ukraine, Russia sees itself as both fighting for a new World Order and control over a reconstituted buffer zone on Russia’s periphery.

Alternative Russian Future Scenarios

In viewing the future alternative possible Russian trajectories, we can focus in on a broad set of scenarios which are differentiated by degrees of change/continuity in terms of political system, regime, and leadership operational code. Each scenario can have different pathways. Time is not neutral: depending on governing assumptions, the longer the war, the more stable or unstable Russia becomes. We can list here the scenarios, broad characteristics, and assumptions embedded within them. Going forward, SCSS seminars will look to identify possible external game changers that would reshape possibilities. For example, if China understands prolonged war weakens Russia, and so threatens system-collapse, Beijing may use its strategic influence to press Russia to negotiate. As FY 2023’s SCSS#12 noted, if organized opposition strengthens and Lukashenka’s regime weakens, a Western-orientated Belarus becomes the best security guarantee for Ukraine and Europe.

“No Putin; No Russia”

This is not an alternative scenario but rather one that extrapolates forward from the present into the future: Putin remains in power. It represents a steady-state continuity model that suggests “war Putinism” is an effective management model, that the longer war continues, the more elites, sub-institutional actors, and society adjust and adapt around incentives for upholding the status quo in war time and the necessity of circumventing sanctions. Russia’s missile production increases, allowing stand-off attacks and the so-called “Special Military Operation” continuity. Putin’s inner-circle become “true-believers.” Putin’s responses to short-term symptoms of dysfunctionality (most notably, Prigozhin’s uprising on June 24, 2023) strengthen the regime over the longer-term. More cynically, those willing to remove Putin are unable and those able are unwilling: Putin’s calibrated coercion and coup-proofing is effective and the regime sustainable. Military “volunteers,” at least according to Russian propaganda, are on the increase. Putin’s management is understood to be critical to the functioning of the limited access order, as it ensures stability, predictability (“rules of game”) and allows for dynasticism (the transmission of power and property to the next inter-married generation). At the same time, Putin is able to “refresh” the “limited access order,” with second tier “war oligarchs” enjoying upward lift. This scenario validates the understanding that the “limited access order” is a durable structure capable of self-reproduction. In this scenario, regime personnel gradually evolve but its policies and Putin’s operational code remain constant. Indeed, since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Putin’s philosophical beliefs only appear to have been reinforced.

“Putinism with Paramount Putin”

This alternative scenario suggests that Putin is able to step-back from the presidency and still exercise a strategic decision-making role from behind the scenes, in the tradition of Deng Xiaoping and Nursultan Nazarbayev. It remains unclear exactly which position in Russia would allow Putin to guarantee his own personal security, mobility, and consumption habits yet still shape events in Russia. However, it is clear that although “Putinism with Paramount Putin” appears a de facto continuity scenario, dual power centers will inevitably entail competition between the two. Competition has second order effects: a weakening of the authority and legitimacy of the sitting incumbent, strategic decision-making paralysis, and potential destabilization become inevitable outcomes. Putin’s current apparent ability to manage “mission” with “money” elites, status quo with renewal, and the risks of military defeat in Ukraine with those of political revolt in Russia, will become much harder. Russian reversals in Ukraine might challenge Putin’s regime, but even if Ukraine restores its 1991 statehood, it does not follow that Russia will admit defeat and it can continue attacks on Ukrainian critical national infrastructure. This scenario suggests that the ‘Collective Putin’ cannot agree on a successor, but there are no popular or consensus alternatives that can step up and realize that a “successors race” is too destabilizing. Regime stability is maintained but while Putin’s philosophical beliefs would continue, his instrumental beliefs would need to consider the dual power center conundrum. In addition, the new sitting president may share the world view, but may have a competing set of instrumental beliefs.

“Putinism without Putin”

This alternative scenario suggests that Putin is no longer in power, but the transfer was peaceful. In other words, either Putin steps down voluntarily and is able to manage his own succession (“operation successor”) or is made an offer he cannot refuse, steps down, and remains a silent powerless shadow, or has died. “Putinism,” though, continues as the ruling “ideology” (paradoxically, its greatest strength is its ability to be all things to all regimes) – Putin’s regime is self-sustaining and can operate without Putin. A combination of belief, convenience, inertia, and a desire for continuity suggests that Russia’s new leadership will rule in name of “Putinism.” Whatever the trigger/pathway that follows Putin’s removal from power, this scenario is predicated on the assumption that the “Collective Putin” leadership can negotiate and bargain, reach a consensus, and that a ‘transition alliance’ would then reflect evenly balanced factional interests. To put it another way, ‘chiefs inside-the-system,’ regional heads, key Federation Assembly senators, and parastatal leaders (e.g. Sechin, Chemezov) can identify a lowest common denominator acceptable technocratic-manager that is not obviously a protégé of any one interest group (e.g. Mishutsin and Sobyanin). Russian history (February 1917, 1953, 1964, and 1991) suggests elites remove or attempt to remove a leader when his strategic decision-making threatens individual and collective elite interests, or perception changes and risks of removal appear less than costs of continuity. In this scenario, the regime certainly changes in terms of leadership composition, and also operational code.

“Neither Putin nor Putinism”

This alternative scenario represents the most radical rupture with the present. As such, this scenario has the most divergent possible pathways and to illustrate this point we can identify three possible options. First, an intra-elite catastrophic breakdown occurs. This could be triggered by an “emergency scenario” (Putin dies or is incapacitated) and the inability of the elite to find a consensus successor. As a result, a “war of protégés” and/or an intra-siloviki war of “all against all” unfolds – think a combination of August 1991 and October 1993 squared. Under succession stress, alliances that look solid can be situational – transitional psychology reshapes transactional calculus (June 24, 2023). Second, it is possible that one powerful faction within the elite emerges and places a strong man as president, who is prepared to draw a line, scapegoat Putin, Shoigu, Kadyrov, and Prigozhin for the war, and unwind tensions with the West to enable forced modernization/reform under conditions of internal repression. This “Liberal Dictatorship” pathway is paradoxical. Lastly, a “Populist People Power” pathway cannot be discounted, suggesting a new counter-elite/opposition leader emerges, as well as constitutional changes that create a more regulated decentralized federation with greater power invested in the regions, the Duma, and less in the presidency. This constrict is then capable of building coalitions for structural economic reform. The new leadership realize that the Putinist system is in fact structured for Sistema, not prolonged conflict with the West and that fundamental reform/modernization necessary. In this broad scenario, “People Power” alone suggests political system change, whereas all others identified here assume “just” regime and leadership operational code all change.

GCMC, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, October 27, 2023

About the Authors

Dr. Graeme P. Herd is a Professor of Transnational Security Studies in the Research and Policy Analysis Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. His latest books include Understanding Russia’s Strategic Behavior: Imperial Strategic Culture and Putin’s Operational Code (London and New York, Routledge, 2022) and Russia’s Global Reach: A Security and Statecraft Assessment, ed. Graeme P. Herd (Garmisch-Partenkirchen: George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, 2021).

Dr. Dmitry Gorenburg is Senior Research Scientist in the Strategy, Policy, Plans, and Programs division of the Center for Naval Analysis, where he has worked since 2000. Dr. Gorenburg is an associate at the Harvard University Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies and previously served as Executive Director of the American Association of the Advancement of Slavic Studies (AAASS). His research interests include security issues in the former Soviet Union, Russian military reform, Russian foreign policy, and ethnic politics and identity. He currently serves as the editor of Problems of Post-Communism.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany is a German-American partnership and trusted global network promoting common values and advancing collaborative geostrategic solutions. The Marshall Center’s mission to educate, engage, and empower security partners to collectively affect regional, transnational, and global challenges is achieved through programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 15,000 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The Clock Tower Security Series provides short summaries of Seminar Series hosted by the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. These summaries capture key analytical points from the events and serve as a useful tool for policy makers, practitioners, and academics.

The articles in the The Clock Tower Security Series reflect the views of the author (Graeme P. Herd and Dmitry Gorenburg) and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.