COVID-19, Russian Power Transition Scenarios, and President Putin’s Operational Code

Executive Summary

- Just before COVID-19 threat became apparent to the wider Russian population, President Putin surprised the world by announcing, inexplicitly, proposals to amend the Constitution of the Russian Federation. These amendments were fast-tracked through two State Duma readings, with an “All Russian vote” scheduled for April 22, 2020. This was delayed as the impact of COVID-19 became apparent.

- COVID-19 stress-tests President Putin’s crisis management skills. In addition, the whole thrust of Putin’s anti-COVID-19 approach brings into question the relevance of the constitutional amendments. The recentralization of power on paper is juxtaposed by a decentralization of responsibility in practice. Populist social guarantees designed to make the constitutional amendments more palatable can be contrasted with the heavy-lifting expected of small- and medium businesses (SME’s) as the state hoards its vast strategic reserves. Thus, in a real time crisis, COVID-19 highlights and brings into question the relevance of Putin’s constitutional proposals, given how the state functions in practice.

- If President Putin wants to retain the ability to shape power succession, his management of COVID-19 must be perceived to be competent enough not to damage the charismatic-historical legitimation of his political authority and tarnish his performance legitimacy. The longer COVID-19 lasts in Russia, the more obvious this gap becomes between stated intent and deeds in practice and the more difficult it will be for President Putin to shape events to his advantage. President Putin’s choices in the face of COVID-19 will determine not just shape power succession processes and so the durability of Putinism itself.

Introduction

As COVID-19 was invisibly penetrating Russian sanitary space, President Putin prepared for his annual Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly to be delivered on January 15, 2020. This speech included a series of surprise proposed amendments to the 1993 Constitution of the Russian Federation. On January 20, 2020, these amendments were submitted as a draft bill to the State Duma. After a two-hour reading on January 23, 2020, the twenty-two presidential constitutional “proposals” were unanimously (432-0) approved. Subsequently, a further 800 amendments have been submitted by the public. The second reading occurred on March 10, 2020 and a vote for the number of presidential terms (currently “two consecutive terms”) to be reset to zero if planned constitutional reforms were passed in a nationwide vote (the “Tereshkova amendment”) was accepted 380-0, with forty-four abstentions. Putin then addressed the Duma:

[This] proposal effectively means removing the restriction for any person, any citizen, including the current president, and allowing them to take part in elections in the future, naturally, in open and competitive elections - and naturally if the citizens support such a proposal and amendment and say “Yes” at the All Russian vote on 22 April of this year.1

According to Article 136 of the current 1993 Constitution, Articles 3-8 can be amended by a vote by the State Duma, Federation Council, and two-thirds of the regional Dumas in Russia’s constituent parts. Both of these votes was taken on March 11, 2020, with the Federation Council voting 160 in favor, one against and four abstentions, and two-thirds in the regional Duma’s achieved. Article 1, “The Fundamentals of the Constitutional System”; Article 2, “Human and Civil Rights and Freedoms”; and Article 9, “Constitutional Amendments and Review of the Constitution” should all be changed by popular referendum, where 50% of eligible voters must vote in a referendum, and 50% of those participating must approve the bill. Although the Kremlin’s reference to a non-binding advisory “citizens” or “nationwide” vote on the amendments is not provided by law, this point became moot as the impact of COVID-19 in Russia became more apparent. President Putin was forced to postpone the April 22, 2020 “All Russian vote” on constitutional amendments; mass gatherings of over 5,000 were barred in Moscow until April 10, subsequently extended to April 30, as part of efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Rhetoric, Reset, or Revolution?

Three hours after Putin’s speech on January 15, 2020, the Medvedev government resigned. President Putin appointed Mikhail Mishustin, former head of the Federal Tax Police, to serve as Prime Minister. Dmitry Medvedev was appointed deputy head of the Security Council four hours before the legal act establishing this new office was introduced into the Duma. The speed of these changes and general surprise suggest advanced secretive preparation and planning, though as Putin subsequently admitted, Medvedev at least “knew what was going on.” President Putin approved the new thirty-one-member executive cabinet proposed by Mishustin on January 21, 2020. Approximately 50% of posts were reshuffled, making the government more technocratic, younger (average age fifty rather than fifty-three), and more professional, with new members having made careers during the Putin era running large-scale projects in the public sector. Change in leadership personnel in the “problem portfolios”—economic development, health, culture, and education—were taken to signal that these respective policy areas will receive greater attention.

President Putin declared that the proposed changes “mean drastic changes to the political system” and justified them in terms of “the further development of Russia as a rule-of-law welfare state where citizens’ freedoms and rights, human dignity, and well-being constitute the highest value.” He added,

. . . this system must be organic, flexible and capable of changing quickly in line with what is happening around us, and most importantly, in response to the development of Russian society. In addition, this system must ensure the rotation of those who are in power or occupy high positions in other areas.2

Putin did not indicate what his role would be within this new constitutional order, except to state that he would not stand for president in 2024 and that the amendments were not designed “to extend my term.”3

Proposed Amendments

The most popular proposals are those that seek to improve socio-economic conditions and uphold traditional values. These have societal support. In addition, a number of more arcane and less relevant amendments from a societal perspective do address governance and have foreign and security policy implications. A key proposal re-emphasizes Russia’s commitment to state sovereignty. Amendment XXX privileges domestic over international law, stating Russian sovereignty is absolute and not qualified in any way by international courts or agreements. This amendment largely reflects the existing law, after a constitutional court ruling in 2015 that stated it can overturn decisions of international courts that relate to Russia. In practice, the Court has only done so twice, but the constitutional court now reinforces this practice. Moscow can invalidate any pre-Putin treaty, including those signed by President Yeltsin. As protections for foreign investors are formally abolished, foreign direct investment will likely decrease. The reduction of such external dependencies increases the instrumental power of state-owned enterprises (SOE’s) through personalized lobbying by informal networks, so consolidating the Putinite regime. Limits placed on citizens’ ability to seek human rights protection through recourse to international courts and agreements suggest improved relations with the West is not a priority. By implication, manipulations of Russian elections by the presidential administration (e.g. State Duma elections 2011) will continue, if not intensify.

Another proposal addresses Putin’s long-standing goal of “nationalizing the elites,” by limiting who can stand for office by tightening residency and citizenship regulations. Putin stated: “Presidential candidates must have had permanent residence in Russia for at least twenty-five years [ten years in the current 1993 Constitution] and no foreign citizenship or residence permit and not only during the election campaign but at any time before it too.”4 Thus, one needs to be thirty-five years older and have lived in Russia for twenty-five years consecutively. This effectively means that future presidential candidates who have studied abroad would be fifty-five years or older. This restriction impacts disproportionately on the wealthy educated expatriate and émigré Russian community (10.5 million, 7% of the total) who may be less loyal to and dependent on the state. This also disciplines the current elite. It makes any ambitious politician wary of spending any time in the West, while promoting the upward mobility of loyal dependent indigenous home-grown Putin protégés. The older generation with foreign connections and passports are eased out, making way for new statist corporatists (gosudarstvenniki) from forty to fifty years old, keen to embrace new technologies and administrative reform, but not political liberalization.

The rest of the amendments adjust the existing governance structures and which positions Putin might occupy after 2024. Most attention has been on the State Council, a body that has existed since 2000 (and functioned in czarist times as an advisory body), but has never had any real power. Putin noted the need to “fix the role and status of the State Council in the Russian Constitution.”5 This body currently meets once or twice a year and is composed of the speakers of the Duma and Federation Council, heads of political parties, ministers, heads of corporations and banks, all regional governors, and some former governors appointed by the president. Under the proposed bill, the president will form the State Council (Gossovet) for the purposes of “coordinated functioning and interaction” of state bodies, and setting out “the main directions” of domestic and foreign policy.6 The details are unclear. One possibility is for the body to be a powerful inter-institutional policy arbitration platform able to discuss key strategic issues, a collective presidency, or Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union equivalent to the Security Council’s Politburo 2.0. Or will it have a more limited weight in the system as a kind of informal chamber of the Russian regional and federal elites? All of Putin’s counterparts will be present in the State Council, so it may become the key arena for backroom horse-trading and informal power games.

The State Duma would be given the additional power to appoint all ministers. This is formal empowerment of the Duma, but it is unclear what happens if the Duma rejects the Prime Minister or ministers. Currently, the president can dissolve the Duma if it rejects his choice for Prime Minister three times. Duma empowerment comes with a caveat: “More responsibility for forming the Government means more responsibility for the Government's policy.”7 Opening up the State Duma even slightly risks opposition voter mobilization and could result in the Moscow City Duma scenario at a national scale. Some semi-opposition groups can be co-opted or side-lined, but elites would likely clash over who will control these new positions, and the levers they offer. In practice, these amendments will not have much impact on the balance of power between executive and legislature.

Putin stated that presidential appointments should follow “consultation” with the Federation Council of “all security agencies” and “regional prosecutors.”8 This increases central control of prosecutors at the expense of regional parliaments and undermines Article 12 of the current Constitution. Putin wants to allow the Federation Council to dismiss Constitutional and Supreme Court judges. The “self-sufficiently and independently” stipulation in Article 10 of the 1993 Constitution is absent from proposals the State Duma considers, limiting further the independence of the judiciary. In effect, the notion of a separation of powers (Article 10 of Chapter 1 of the 1993 Constitution) is discarded.

COVID-19 Stress-Testing Alternative Power Transition Scenarios?

Why were these proposals announced on January 15, 2020, twenty years into the Putin era and four years before 2024? Why after the announcement were the proposed amendments rammed through the State Duma at such speed? Speculation over the reset and reconfiguration suggested a number of alternative directions of travel.

First, Putin is an institutionalist and seeks to transform the regime that he created into an institutionalized state, involving increased checks-and-balances and limited pluralism to embed Putinism. This can as an unintended side effect liberalize and even democratize Russia’s political system. This understanding, it turned out, was overly reliant on President Putin’s words and stated intent, rather than actual actions and deeds. A second explanation argued precisely the opposite. Russia is an unambiguously authoritarian regime. President Putin attempts a constitutional coup d’etat from above (a “state coup”). Putin transfers more power to himself; destroys regional and municipal self-government and the independence of the judiciary to create a constitutional monarchy: strengthens the State Council and Duma making actual differences between “approve” and “consultation on” appear nominal; and increases presidential powers.

Third, the proposals could be indicative of Putin’s predictive thinking. By January 15, 2020, Putin knew something the general public in Russia and internationally did not. His proposals to reform the constitution were, in hindsight, indicative that Putin’s predictive thinking understood that things are going to get worse. Given the COVID-19 outbreak occurred in 2019, and that first U.S. intelligence reports even in November 2019 were warning of the coming virus, it is more than likely that Russian intelligence services were reporting the same to President Putin. The coming disruption would be multifaceted: economic and societal depression; growth of protest potential; and a resultant decline in Putin’s popularity, triggering elite infighting might all have been considerations. Putin may have realized that Russia economic cushion ($570 billion in the Bank of Russia and $124 billion in the National Welfare Fund) could not quell the political effects of COVID-19. Associated uncertainty raised the threat that his president-for-life project option would be derailed, hence the need for speed.

Alternative Transfer for Power Pathways and Scenarios

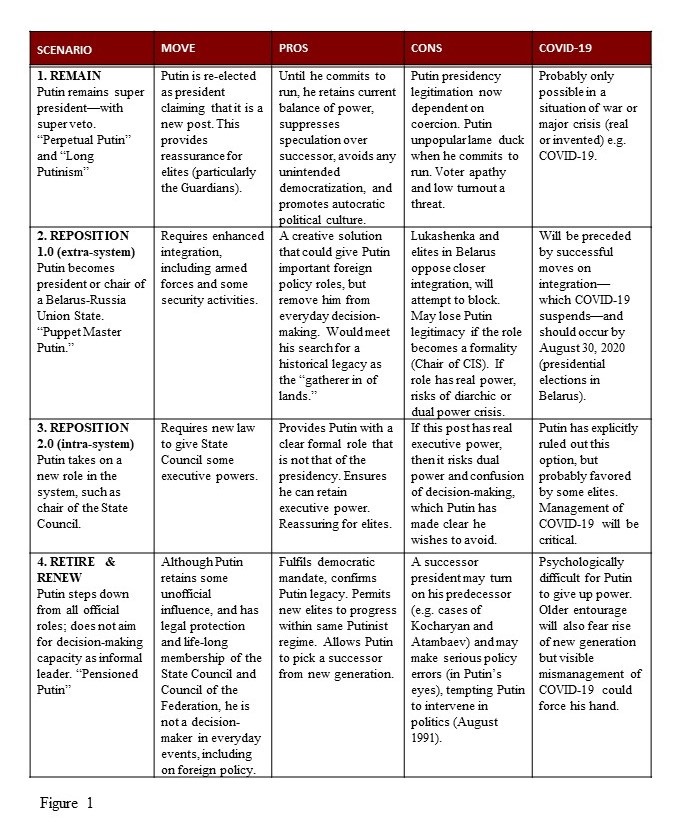

As President Putin’s words are never a good indicator of his deeds, we can identify possible alternative types of succession scenarios that secure Putin’s wealth, personal security, and mobility are compatible with the constitutional amendments, weigh up pros and cons, and assess the possible impact of COVID-19 on each (see Figure 1, below).

We can look at the first three in greater detail. First, the “Remain 1.0” scenario suggests a “Perpetual Putin and Long Putinism” or new first term “Reluctant Consent” way forward. In this case, Putin solves the “2024 problem” by resetting the clock. This appears to be Putin’s preferred scenario as proposed Constitutional changes further strengthens the presidency in three dimensions. The defense-security and law enforcement bloc (prosecutors/judiciary) is further centralized under the presidency. President Putin clearly states that the president

must undoubtedly retain the right to determine the Government's tasks and priorities, as well as the right to dismiss the prime minister, his deputies and federal ministers in case of improper execution of duties or due to loss of trust. The president also exercises direct command over the Armed Forces and the entire law enforcement system.”9

Indeed, and as expected, the Constitutional Court (eleven of whose fifteen members were appointed by Putin, including the Chief Judge) supported the rest of the presidential clock.

The amendments are compatible with the “Remain 1.0” scenario, though this solution is far from ideal, given Putin has repeatedly stated that he will leave the presidency in 2024. Nonetheless, given the clock is reset, Putin can extend his power until 2036 not by abolishing term limits (as in the case of Xi Jinping) but by amending them (as in the case of Belarus, Azerbaijan, and Turkey). Alternatively, and in principle, Putin could serve 2024-2030, castle with Medvedev, and return to the presidency for his new second presidential term between 2036-2042, or, indeed Medvedev could be president 2024-2036, with Putin beginning his new “first” term 2036-2042 and his “second” to 2048.

Second, the “Reposition 1.0” scenario suggests a “Putin the Great and Greater Putinism: Bring Back Brother Belarus State Union” way forward. In this case, Putin implements the 1999 State Union Treaty and becomes life-long Chair of the Supreme State Council of the Russia-Belarus State Union announced on the occasion of “Victory Day” (May 9, 2020). In 2020, this falls on the 75th anniversary of both the Great Patriotic War, the cornerstone of Russia political identity, and the establishment of the United Nations (U.N.), the foundation of Russia’s Great Power identity. Discussions to date point to a rather loose union, with still two formal states, but joint tax and customs system, security forces, single currency: a shared institutional framework with supra-national bodies in some shape and form. “Soft annexation” that allows for the legal existence of two separate states (two foreign ministries, U.N. votes etc.) would blunt western reaction. Putin’s recent highly public re-litigation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as an information tool to divide and disrupt rather than reconcile and unite sets the psychological environment for such a “breakthrough” or “break out” of “encirclement.” Putin promotes himself as guardian and guarantor of a new Yalta-Potsdam system. This union consolidates Putin’s historic role of “gathering in the Russian lands” and people (nine million) as Russia extends its borders with EU and NATO states by 600 kilometers.

However, COVID-19 has forced Russia to suspended integration, as its borders were closed between March 19 and May 1, 2020. In addition, the dual decision-making and power centers problem is still present. For Lukashenka, any change of position represents a demotion. Is his verbal opposition to political integration and his intensification of multi-vector negotiations (with China, the United States, and Norway) indicative of a genuine commitment to Belarusian statehood or a negotiating tactic to strike a better bargain? The proposed Constitutional amendments do not preclude a State Union and if COVID-19 overwhelms Belarus, the State Union could be perceived as a panacea. In any event, Putin solves the “2024 problem” through foreign policy.

Third, the “Reposition 2.0” scenario suggests a “Putinism with Paramount Putin: Densyaopinizatisitskya” or a Kazakh way forward. Putin is prepared to exercise power from a position other than the president and prepares the ground through a smooth, slow, gradual transition. There are successful and unsuccessful precedents to act as a guide. Deng Xiaoping oversaw and influenced rotations of power in the third and fourth generations of post-Mao leadership as First Vice President of the State Council and Chair of the Central Military Commission. After his resignation in 1990, Lee Kuan Yew held the permanent Cabinet post of “First Minister” and then “Minister Mentor” until his death in 2015. More recently, Nursultan Nazarbayev’s management of power transition and succession is characterized by him voluntarily giving up power mid-term (March 2019), in a carefully choreographed manner marked more by continuity in control of multiple levers of power than change. Nazarbayev remains Chair of the Security Council, leads the Nur Otan party, has the title of “First president of the Republic of Kazakhstan–Yelbasy,” and receives immunity from prosecution, with his assets and family fully constitutionally protected. However, Leonid Kuchma (Ukraine), Mikheil Saakashvilli (Georgia), and Sergz Sargysan (Armenia) all failed to retain power when attempting to create a new post-president position of power.

In effect, Putin looks to solve the “2024 problem” through domestic policy changes. This scenario is based on three assumptions. The first is that Putin seeks to utilize constitutional change to rebalance power between the President and Prime Minister and boost the power of alternative non-elective collegial bodies such as the State Council and/or Security Council. The second assumption is that, given this, these bodies represent a good enough open-ended (no term limits) platform to dominate Russian foreign and security policy and strategic decision-making inside Russia. Medvedev as deputy chair of the Security Council can ensure some enhanced control over the security services. Third, we must assume that to effectively exercise veto power, Putin must maintain directing control of Federal Security Services, National Guard, prosecution bodies and the state budget and obschak, a reserve shadow funds notebook that details who keeps what assets where.

Constitutional Amendments and Putin’s Operational Code

The unanticipated January 15, 2020 announcement highlights the instrumental belief set (how Russia should engage the world) in Putin’s operational code. It was strategic surprise to domestic elites and the state media, allowing Putin to demonstrate that he is the decision-maker. Putin sets the agenda as a vozhd (chief) very much capable of manual control, not a lame duck. The announcement was also laden with ambiguity. The lack of clarity over his desired end-state is a useful management technique, giving Putin maximum room for maneuver while circumscribing the mobility of others. In addition, for twenty years Putin promised no change to the Constitution, then announces “drastic change” and to strengthen the power of the State Duma and limit the presidency to two terms. This underscores the notion that Putin’s words are not a good indicator of his intent. The surprise March 11, 2020 move to reset the clock is in its own way ambiguous: Putin can run but he is not obliged to run for in effect a fifth term. Until Putin commits to run again in 2024 he has leverage over elites.

When the postponement of the “All Russian vote” became a necessity, Putin begins to use the triple threats of COVID-19, breakdown of OPEC+, and global economic slowdown as justification for continuity. Russia needs a “strong hand” in troubled times. After March 11, 2020 and the reset, Putin’s supporters offered as justification the notion that Western states would have taken advantage of a weak post-Putin leader and Russia and foisted perestroika-II on Russia after 2024 causing collapse. This was a defensive reactive preventative occupation of the presidency after 2024 to stop something worse from being inflicted on Russia, according to this rather tortured logic. “Putin is our resource” and “this is no time for revolution” are the watch-words of the day.

For authoritarian regimes, the absence of intra-elite political conflict is the greatest indicator of regime stability. Putin’s constitutional changes represent a deep state “Fourth Way” approach to avoiding this pitfall. Putin seeks to avoid Stalin’s first way example in the early 1950s of no succession plan, resulting in a power struggle. The second way, non-functional stagnation and gerontocratization (“coffin carriage race”) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, is leapfrogged. Best of all from a Putin perspective, the third way offered by Gorbachev scenario (a projected Putin-led perestroika II) of uncontrolled liberalization and political breakdown in the late 1980s is sidestepped. The “Fourth Way” approach sees Putin redistribute leverage in his administration to avoid intra-elite conflict. He reformats the structure of his agency by reshuffling the government, changing the balance between branches of power and between formal and informal processes using administrative and legal mechanisms. He creates a power transfer infrastructure that can manages the transfer of power from older elites made up of loyal personal friends from his generation (1970s), who find safe spots in the Federation Council or State Council, to younger elites represented by loyal professionals who came of age in the first decade of his rule (2000s)—the successor generation—who take over the day to day running of the country.

COVID-19 and the Constitutional Amendments

Might this be a miscalculation given the inherent unpredictability of COVID-19? Rather than reducing uncertainty in elites, launching Constitutional reform in a time of COVID-19 creates turbulence and increases risk. Harold James discusses how COVID-19 forces tradeoffs between political liberty, economic growth, and public health.10 He suggests that in this trilemma, states cannot be healthy in all three dimensions. States could, for example, adopt a China-style algorithmic authoritarian surveillance state with no political liberty but the prospect of post-COVID economic growth with a healthy labor force. Alternatively, states may preserve a healthy public and political liberty but kill their economies. James argues that such trilemma tradeoffs are never absolute in that part of the trilemma never fully manifests itself, so everything is negotiable and some of the trades are even illusionary.

In the case of Russia, the reality of COVID-19 as set against the rhetoric of Putin’s constitutional amendments has the ability to wound, limit, and undermine the Putin project. As of April 12, the number of those infected nationwide had risen to 15,770 and the total number of deaths in Russia stood at 130. More than 1.2 million COVID-19 tests had been performed, according to consumer watchdog Rospotrebnadzor.”11 On paper, the Constitutional amendments recentralize power even further. In practice, COVID-19 has Putin adopting an almost forced federalization approach, insisting on decentralizing decision making and responsibility to the regions and localities, which impose strict quarantines. Technocratic managers expected to act independently are in fact governed by Kremlin-imposed Key Performance Indicators and these appointed governors operate in systems characterized by bureaucratization, centralization, and inertia. Nevertheless, failures will be regional and the buck will stop at the regional governor (fired), while successes will be attributable to Putin’s firm leadership.

Although some regions are resource rich, all are cash poor. Despite this, President Putin also transfers the costs of COVID-19 from the state with its large cash reserves onto SME’s. This statist approach will weaken the private sector and entrepreneurs, allowing SOE’s to further dominate economic activity in Russia. Putin’s approach to COVID-19 thus accelerates existing economic trends towards statism and corporatism. President Putin privileges the promotion of his inner circle and their narrow interests over the public good at a time where conditions in wider society deteriorate. Putin’s core support is in the small cities and towns of the provinces, where SME’s are fewer in number, investments in long term health care smaller, and social safety nets weaker. Is Putin in danger of losing this constituency? Given the links made even by Moscow Mayor Sobyanin between COVID-19 and Courcheval (rich Russian’s returning from ski resorts in France imported the virus into Moscow), might we see elite societal tensions, as well-connected and resourced Moscow is protected while poor peripheral communities suffer?12

Conclusion

As many Russians have a relative or friend in Moscow, the epicenter of the epidemic, positive perception of COVID responses in Moscow are critical for national unity and functioning of the Russian economy. For now, a VTsIOM public opinion survey in March 2000 reflected a rally around the flag effect: although COVID mortality numbers are increasing while Russia’s economy deteriorates, Russians are optimistic and trust in government rises.13 While the delay to the “All-Russian vote” slated for April 22, 2020 to an unspecified future date generates increased tension in the elite and fears of a leadership vacuum, a quick COVID-19 recovery could be to Putin’s advantage. It provides President Putin extra time to build support and, ideally, the “all-Russia vote” occurs in the warm afterglow of not only “victory over the virus” but in the context of a May 9, 2020 Victory Day Parade in Moscow. Snap State Duma elections could also be held at the same time, consolidating Putin’s power and prestige and securing his control over the succession process.

However, such an outcome cannot be guaranteed. Variables such as the health care section’s ability to “flatten the curve” before it collapses; length of immunization; the possibility of secondary infections; and a new strain of COVID-20 surfacing all suggest an extended turbulent and cyclical period of peaks and troughs. In this context, President Putin will be under increasing pressure to take ownership of what by now would be a more intractable problem. Popular support for Putin himself and then for his increasingly irrelevant constitutional amendments will fall. The dangers that animated Putin’s predictive thinking would have been realized. The “Collective Putin” would be empowered, elite rivalries would increase, and Putin would be less able to shape the succession process. The over-concentration of power in the Kremlin will be understood as a weakness not a source of strength; a core task will be to restore Putin’s compromised authority.14 A rewrite of the constitution to actually rebalance political, economic, and civic power would allow a re-federalization, a restructuring of the economy, and political liberalization. Russia could modernize. Instead, we must contend with the weight of Russia’s strategic culture and the ingrained durability of President Putin’s operational code, so a more likely approach to re-legitimation will be to focus on achieving quick “victories” against weaker neighbors in the post-COVID-19 context.

For Academic Citation

Graeme P. Herd, “COVID-19, Russian Power Transition Scenarios, and President Putin’s Operational Code,” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 51 April 2020, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/covid-19-russian-power-transition-scenarios-and-president-putins-operational-code.

Notes

1 “Text of President Putin's address to the Duma on constitutional amendments,” President of the Russian Federation website, Moscow, in English, March 10, 2020. Unless otherwise stated, all foreign language sources are accessed through the BBC Monitoring database.

2 “Kremlin transcript of Putin’s annual address to parliament,” President of the Russian Federation website, Moscow, in English, January 15, 2020.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Harold James “Navigating the Pandemic Trilemma,” Project Syndicate, April 6, 2020: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/navigating-covid19-economy-health-democracy-trilemma-by-harold-james-2020-04, accessed April 7, 2020.

11Report: “Coronavirus in Russia, 12 April 2020” BBC Monitoring, April 12, 2020.

12 Stanislav Zarakhin, “Buryatia’s Coronavirus Patient ‘Number One’ Exposes Social Divide,” The Moscow Times, April 4, 2020: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/04/07/buryatias-coronavirus-patient-number-one-exposes-social-divide-a69900, accessed April 10, 2020.

13 Interfax News Agency, Moscow, in Russian, 1423 GMT, April 10, 2020.

14 Pavel Baev, “Pondering upon Post-Pandemic Revolutions…and Russia,” ISPI (Italian Institute for International Political Studies), April 10, 2020, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/pondering-upon-post-pandemic-revolutionsand-russia-25754, accessed April 12, 2020.

About the Author

Dr. Graeme P. Herd is a Professor of Transnational Security and Chair of the Research and Policy Analysis Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. He directs a Russian Strategy Initiative funded and GCMC-led research project that examines Russia’s strategic behavior. This article is based upon research undertaken for Dr. Herd’s presentation on April 7, 2020 in support of the Eurasian Foreign Area Officer (FAO) program and benefitted from the questions and comments from FAO’s and those participating remotely.

Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)

This program of research, led by the GCMC and funded by RSI (U.S. Department of Defense effort to enhance understanding of the Russian way of war in order to inform strategy and planning), employs in-depth case studies to better understand Russian strategic behavior in order to mitigate miscalculation in relations.

The Marshall Center Security Insights

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 14,000 professionals from 156 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Security Insights series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.