Europe's Dependence on Russian Natural Gas: Perspectives and Recommendations for a Long-term Strategy

Chapter 1 – Russia and the European Natural Gas Market

Introduction

The European Union 27 currently rely on Russia for almost 38% of their imported natural gas;1 this dependency will become significantly greater if European states implement their currently formulated energy policies. With plans to phase out nuclear power in several European countries, the EU goal to reduce coal consumption thereby lowering greenhouse gas emissions, and the depletion of domestic sources of gas, reliance on Russia will rise to 50 to 60% of all gas imports within the next two decades if different energy policies are not adopted.2 The EU and greater Europe will soon find themselves in an extremely dangerous position due to the ever-increasing dependence on Russian natural gas. These countries must work together now to produce a coherent diversification strategy.

While the current EU energy policy is forward thinking in its targets for renewable energy, economizing, and emission reduction, it falls short in its failure to recognize the security threat of the increasing dependence on Russian hydrocarbons – in particular, natural gas. This paper proposes a diversification strategy with concrete steps that can be taken in a variety of energy policy areas to create, over the long-term, a more balanced approach to meeting energy needs. Europe must undertake such a strategy not only because over-reliance on any one source represents unsound policy, but more importantly because domination of the European market has been a clear and calculated goal that an unreliable Russian administration has been working towards for several years. Russian domination of the European natural gas market would give the Kremlin incredible leverage in its dealings with its European neighbors. Europe’s dependence on Russia for natural gas already profoundly affects the freedom of action of certain European states and will increasingly erode European sovereignty. Several factors could mitigate Russia’s capability to monopolize natural gas markets on the European continent. This article also discusses these factors, in particular in the context of the kind of steps greater Europe could take to ensure Russia does not realize its goal of reasserting coercive influence through its ‘energy weapon.’

Why Natural Gas is so Critical in the Energy Mix

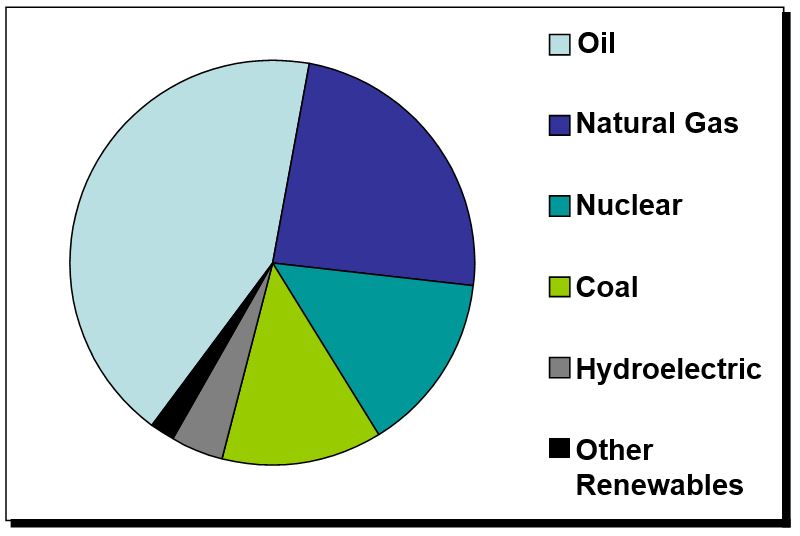

Natural gas plays a critical role in energy consumption worldwide; Europe is no exception. The EU accounts for 17% of world energy consumption and uses the same proportion of annual world natural gas production.3 Analyzing energy by source, EU usage breaks down into the following categories: oil 43%, natural gas 24%, nuclear 14%, coal 13%, hydroelectric 4%, and other renewable sources (such as geothermal, biomass, wind, and solar) 2%.4 Contrary to popular conception, the vast majority of electric power is generated through the burning of hydrocarbons to heat water for steam to run turbines. Hydroelectric, nuclear, and renewable sources of electricity combined create far less than is produced by gas, coal, and oil. Additionally, natural gas is the preferred hydrocarbon for electric power generation because it is the cleanest burning and is comparable in price to coal.5 Despite this, natural gas is probably best known to the consumer for its domestic uses for heating, cooking, and cooling; residential usage accounts for approximately 22% of overall natural gas consumption.6

In addition to commercial power production, many industrial applications depend on natural gas. It is the basis of many chemical products, fertilizers, and pharmaceuticals because it is a cheap source of butane, ethane, and propane. Additionally, it is the base ingredient for various plastics, fabrics, and antifreeze. In a compressed form, it is a fuel source for combustion engine vehicles. While relatively few natural gas filling stations exist, public buses in Europe increasingly use this fuel, which pollutes far less than gasoline and diesel fuels.7 Given the multiple uses of natural gas, its advantageous price in relation to renewables, and the emission control advantages, most energy projections show natural gas growing to about one-third of the entire European energy mix by 2030, pulling almost even with oil in relative importance.8

Chart 1: EU Energy Usage by Type (Chart by Author)

Fragmentation of Pricing and the European Natural Gas Market

Due principally to the potential of pipeline and container vessel, oil trades at market prices that vary only moderately worldwide (3.7% in 2005). In contrast, gas in its natural state can be delivered economically only by pipeline, making it far more susceptible to regional pricing (31% price variance by location in 2005).9 As a result, natural gas suffers from highly fragmented pricing; its cost varies substantially due to a variety of factors including wellhead, long-distance transportation, and local distribution costs.

Natural gas can be liquefied by a process of cooling it to 260°F (162°C ), which reduces its volume 600 times, making it transportable by container ship. Since this process is expensive, for most economies liquefied natural gas (LNG) only supplements pipeline gas.10 Liquefying natural gas requires exceptionally large facilities (commonly referred to as trains) where only economies of scale make the process viable. This further limits the exporting and importing of LNG to producers and consumers capable of investing in multiple hundred million dollar terminals. The fact that transportation of natural gas in a liquefied state by container ship causes some to be lost due to vaporization en route further complicates and fragments pricing.11 While pipeline gas is also lost in transit due to inevitable pipeline leaks, the length and duration of shipment plays a greater role in the economics of LNG transport, compounding the tendency of price regionalization in both the gaseous and liquefied forms of the commodity.

In Europe, with only three main external suppliers,12 natural gas normally sells in long-term contracts of up to 25 years. The contracts typically obligate the buyer to purchase a set minimum amount, protecting the producer who must make large investments in not only exploration, but also in pipelines, pumping stations, and storage facilities. Pricing of natural gas in Europe depends primarily on what the market will bear in relation to the prices of alternative fuels.13 Because oil is the closest substitute for natural gas, oil prices drive the price of gas. The huge increases in oil prices over the past several years have brought with them corresponding hikes in European natural gas prices, in large part because long-term gas contracts usually include variable pricing to compensate for swings in the prices of petroleum products. This regionalization of price due to the difficulty in offsetting pipeline gas with LNG and the overall reliance on limited long-term contract providers of gas demonstrate how much more leverage a gas provider has than an oil producer in setting the pricing terms. Until LNG becomes a world commodity like oil with more economical tanker delivery, fragmentation of natural gas prices will continue. That said, the severity of regional price differences is slowly decreasing.14

For the aforementioned reasons, a large regional gas exporter can be a pricesetter rather than a pricetaker. As a gas producer and exporter, the Russia Federation has no peer. In 2005, Russia produced 22% of the world’s natural gas.15 With 47.55 trillion cubic meters of natural gas (m3),16 Russia possesses 27.5% of the world’s reserves. The next closest in terms of proven resources are Iran, with 15.9% of world reserves, and Qatar, with 14.9%. No other individual country accounts for more than four percent of world gas reserves. Russia has the natural gas equivalent of Saudi Arabia’s dominance (25%) in the world’s oil reserves.17 Because of the phenomenon of regionalized pricing in natural gas, Russia’s dominant position on the European market gives it leverage far greater than that of a typical energy producer.

Europe’s Increasing Reliance on Imported Hydrocarbons

The European Union (EU) currently imports 50% of its energy requirements in the form of hydrocarbons. Projections for the next 2030 years predict these imports will rise to 70% of all energy consumed in the EU.18 Numerous factors simultaneously drive the increased reliance on external sources of hydrocarbon energy. Primary among these is the simple fact that most of European oil and gas resources are either depleted or in decline.19 Within Europe (excluding Russia), the prospects for domestic production are virtually nonexistent, as many countries have no reserves. Currently, only Norway and the Netherlands, at 1.4% and 1% of natural gas world reserves, provide a limited intraEurope offset to absolute dependency,20 however, an unsubstantiated claim of a large gas field in Hungary could slightly alter the market dynamics in Central Europe.21

While domestic natural gas supplies in continental Europe are dwindling, coal remains in abundant supply. Poland, Serbia, Germany, and the Czech Republic alone have combined recoverable coal reserves in excess of 47 billion tons.22 The Kyoto Protocol carbon dioxide emissions targets preclude increasing coal’s usage for generating electricity. In accordance with the Kyoto Protocol, the goal for greenhouse gas emissions for the EU15 in the period 20082012 is to be 8 percent lower than 1990 levels.23 Natural gas, as the cleanest burning of the hydrocarbons, becomes the fuel of choice to reduce emissions and yet meet energy demands, despite the relative abundance of coal, particularly in Central Europe.

Nuclear power could also be a significant offset to gas-produced electric power, but there is strong social and political resistance to its use in countries such as Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden. Germany’s decision to be free of nuclear power by 202324 will greatly increase its reliance on hydrocarbons to generate electricity over the coming decade, in particular natural gas. France’s decision in 1973-74, after the first oil shocks, to bolster its nuclear power generation industry shows the extent to which this source can reduce foreign dependence on hydrocarbons. With 56 nuclear reactors annually producing 430 terawatt-hours, it is estimated that France saved €13.5 billion in 2006 by not relying as heavily on imported natural gas and also reduced emissions of CO2 by 128 million tons.25 A comparison of the electricity sectors of France and Germany vividly illustrates the effects of a nuclear diversification strategy. France consumed 85% of the electric power that Germany did in 2003, 433.3 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) versus 510.4 billion kWh. 77% of France’s electricity was nuclear-generated, with only 8.2% coming from fossil fuel. Germany’s mix was 29.9% nuclear and 61.8% fossil fuel. France imported 40 billion m3 of natural gas to Germany’s imports of 85 billion m3.26 In essence, Germany annually spends almost 1% of its GDP for the import of natural gas.27 This figure will rise significantly as Germany phases out nuclear power.

Renewable energy sources also provide excellent opportunities for diversification from gas produced electricity, but progress has been slow in Europe for economic reasons – renewables currently cost more than other methods of electricity generation. The production cost of one kWh of electricity from gas-powered and nuclear power plants both average 3.2 € cents; the far more heavily polluting coal-fueled power generation is comparable at 3.7 € cents per kWh.28 In comparison, electricity produced by a turbine in an average wind location costs about 8 € cents per kWh, making it more than twice as expensive as gas, coal, and nuclear.29 Other renewable forms of electric power generation cost even more, making natural gas the apparent choice for power generation while simultaneously reducing levels of pollution.

Europe’s Energy Dependence on Russia

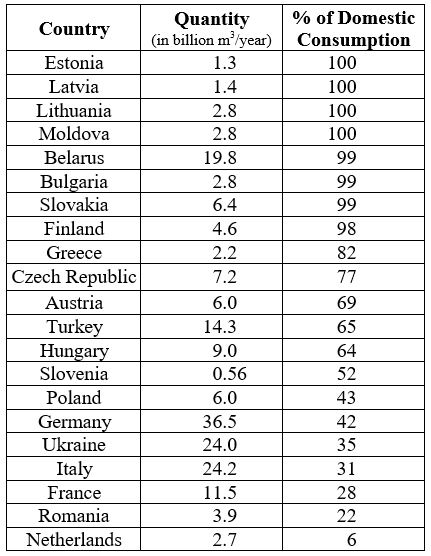

Most of the EU’s natural gas comes from only three external producers – Russia, Norway, and Algeria. At 37.7% of the EU 27’s total gas imports in 2005, Russia is by far the biggest gas supplier to the continent.30 Generally, the farther east one goes in Europe, the greater the reliance on Russian gas imports, to the extent that seven European states of the former Warsaw Pact and Soviet Union rely on Russia for over 99% of their natural gas. Almost all Central and Eastern European countries depend on Russia for the majority of their natural gas consumption.31

Looking 25 years out, it is estimated that 80% of the EU’s natural gas will be imported, with Russia providing up to 60%,32 equating to one fifth of the overall EU energy mix coming from Russia in the form of pipeline natural gas. This figure does not include the energy the EU will import from Russia in the form of oil, which is estimated to be as much as another one-tenth of the total energy mix.33 Thus, as the world’s major price-setter for natural gas, Russia— supplying one-third of the EU’s energy in 2030—will be in a position to use its energy supplies as levers of control by dictating terms. The negotiations that transpired with Ukraine at beginning of 2006 and with Belarus in the closing days of 2006 show the huge economic and political leverage Russia commands with countries dependent on its energy.

A common phrase that is often repeated in Euro pean political discussion is “the EU and Russia are mutually dependent on one another respectively as buyer and supplier of energy.” This conventional wisdom oversimplifies the situation, perhaps in an attempt to make the facts palatable to EU constituents. Realistically, without serious concerted efforts on the part of the EU states, Russia will have the upper hand in this relationship. Energy demand, particularly in highly developed economies, is not price elastic. Quite simply, demand will remain constant almost without regard to price; given the choice of a cold, dark home or paying exorbitant prices, Europeans will do the latter. The mutual dependence theory espoused by European politicians also fails to take into account how Russia has been using these hydrocarbon revenues; Russia has been accumulating a large part of them in an oil stabilization fund. Since this revenue is not going to non-discretionary funding, it strongly indicates that Russia could show more perseverance if these revenue streams were interrupted than their European customers could tolerate disruptions in energy supply.

Table 1: Russian Natural Gas Imports as a Percentage of Domestic Consumption34

The Effect on the European Market of Opening Pipelines to China

Another sobering thought is that while Europe is now Russia’s primary gas customer, the booming economy of China makes alternate pipeline routes to the south and east economically viable. One supplier with two voracious customers is a prospect that has not eluded planners in the Kremlin. Europe has only a few more years of convincing itself that a reciprocal dependence relationship occurs; with gas routes to Asia, Russia will have increased demand and a choice of customers. Just as Russia was able to shut off natural gas to Ukraine on January 1, 2006, diversification of its customers will give Russia enormous levers of power and control if Europe does not quickly diversify from its increasing gas dependence.

According to press releases from Gazprom, Russia’s 50% state-owned natural gas consortium, which controls 17% of the world’s gas reserves and over 60% of Russia’s reserves, gas shipments to China will commence in 2011 when the Altai pipeline is completed.35 China’s natural gas consumption in 2004 was only slightly higher than its domestic production, 47.5 billion m3. By 2011, China’s gas consumption is expected to more than double to 103120 billion m3/year.36 Gazprom’s plan is to invest $4.5 $5 billion to build a pipeline stretching 2,800 kilometers, which would allow delivery of gas from Eastern and Western Siberian fields to Northern China. Gazprom estimates that the capacity of deliveries to China could reach 68 billion m3 per year in the next decade.37 In 2005, Gazprom exported 156.1 billion m3 to the EU 27 and 76.6 billion m3 at subsidized rates to former Soviet Union countries, with Ukraine accounting for almost half of the former Soviet Union consumption.38 It should be added that Gazprom, as sole owner of Russia’s Unified Gas Transportation System (UGS) – a network of pipelines and gas compressor stations that stretches 155,000 kilometers – has exclusive rights to export Russian natural gas.39 The implications of this are quite important for the European consumer. Within four to five years, the Russian government, through its agent, Gazprom, will have a market and delivery means to China for approximately 30% of the gas it currently sends west. The leverage that this choice of customers provides will allow Russia to write extremely favorable long-term supply contracts.

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of the China market for Europe is not only the demand aspect, but the fact that Russia may soon prefer to deal with China. A quick look at the map shows that Russian gas can pass directly to China with no transit countries. For Gazprom, this means no transit fees and no negotiations of terms with unreliable transit partners. Russia’s experience with Ukraine and Belarus in early and then late 2006 were two-sided; they indicated not only the leverage that Russia exerts with natural gas, but also the price concessions that must be given to allow gas transit on to their EU customers who pay full prices. The prospect of Chinese partners paying market prices without the fear of siphoning or transit duties is enticing. One final alluring aspect of the Chinese market is that it is far closer to potential Eastern Siberian fields40 than European consumers, again being preferable to Gazprom from an economic and infrastructure perspective. Pipelines have leakages and also require pumping stations to move the gas under pressure through the pipes; the farther the transit, the more expensive and the higher the rate of gas loss.

Russian Gas versus Oil

EU diversification away from Russian natural gas is far more critical than from Russian oil, even though Russia may be a provider of up to 11% of the EU’s overall energy in the form of oil over the next two decades. While oil will almost certainly generate huge revenues and favorable trade balances for Russia, it will not be as likely a source of Russian political and economic leverage as natural gas. There are several reasons for this assertion.

First, estimates of Russia’s total share of the world’s known oil reserves range from 4.5% to 6%.41 Russia ranks eighth in the world for oil reserves – a far cry from its dominant position in the world’s percentage of natural gas.42 Even using figures for reserve growth and still undiscovered fields, the most favorable estimates for Russia rise to 281 billion barrels, representing 9.5% of the world’s oil supply in a best-case scenario. In line with these estimates, the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts Russia will produce about 8.5% of the world’s export oil in 2030.43 This capacity is impressive and worth billions of dollars per year, but it is not significant enough to give Russia a price-setting role in world markets. Quite simply, European consumers have the option to look elsewhere if they do not like Russian oil terms.

A second key reason oil will not provide Russia the same leverage over Europe is that oil does not experience the same fragmentation and regionalization of price that gas does. Easily and economically transported by container ship, oil can be sold to markets worldwide. Unloading oil at ports is far simpler than the regasification process required for LNG. Russia’s dominant position in the European gas markets gives it pricing power as well as the upper-hand in negotiating long-term contracts. With this leverage, Gazprom has been highly successful at writing contracts that roughly peg the price to petroleum products, but with clauses protecting the seller.44

Russia’s ability to dictate prices is even greater with Eastern European and former Soviet countries that are entirely reliant on Russia for their natural gas. The recent natural gas deal signed with the Republic of Georgia exemplifies this fact. Despite a dramatic fall in oil prices from their 2006 summer highs, in December Gazprom locked in a gas price of $235 per 1000 m3 for gas throughout 200.45 This price basically mirrored that paid by Western European consumers who had locked in prices when oil was significantly higher.

While the LNG market has grown significantly and the number of short-term contracts is increasing, it is difficult to predict whether natural gas in its pipeline form and LNG will become a single commodity with relatively similar prices worldwide any time soon. Regardless, Europe would have to invest more than it has already in regasification sites to be able to import enough LNG to offset the huge expected increase in demand for Russian pipeline-delivered gas. Because of all these factors, Europe could look for another seller of oil in the face of unreasonable terms from Russia, while natural gas, in both its pipeline and LNG form, usually require lengthy procurement lead times, often up to eight years, tied to long-term contractual agreements. Europe could easily find itself reliant on Russian natural gas for 20% of its energy requirement and for reasons of time, quantity, and deliver-ability, have insufficient alternatives on the world market if Russian terms were excessively demanding.

To put a monetary value on this level of gas reliance, given consumption projections and assuming Gazprom could meet the demand, the EU could conceivably be importing 270 billion m3 per year from Russia by 2030.46 At average contract prices of $230-250 per 1000 m3, which equals $65 billion per year. Since gas and oil prices will certainly be higher in two decades, especially given that oil and gas exploration in the future will be far more expensive as the economically easy to exploit locations are being depleted, the real figure will be far higher.

The Possibility of a Gas Cartel

In November 2006, a confidential study by NATO economics analysts was leaked to news agencies. Although publicly unavailable, the basic tenet was that Russia may be attempting to build a gas cartel including Algeria, Qatar, Libya, the former Soviet Republics of Central Asia, and perhaps Iran.47 Deputy Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov responded quickly to the study: “Our main thesis is interdependence of producers and consumers. Only a madman could think that Russia would start to blackmail Europe using gas, because we depend to the same extent on European customers.”48 This affirmation of mutual dependency seems to have been made only to assuage European politicians, for it deviates from a more recent statement made by Alexander Medvedev, Deputy Chairman of Gazprom, in a December 2006 interview. Medvedev defended Russia and his firm’s actions in conjunction with raising prices to Belarus and Georgia: “If Europe is ready to buy more gas, we are ready to sell more. But if not, we have other customers – for instance, China.”49

Several reports soon followed the news of the NATO study, suggesting that the likelihood of a gas cartel led by Russia would be extremely small. Energy Business Review and The Financial Times both published well-reasoned economic analyses of the difficulties Russia would face in establishing and controlling a gas cartel.50 Chief among the obstacles would be controlling the agendas of such widely differing partners. Producers would also be unlikely to allow the control over their production allotments necessary to manipulate world supplies, because, as previously noted, many of the aspects of the gas business require large economies of scale to be highly profitable. Gas contracts, often 10-25 years in length, differ from short-term oil contracts, making it difficult for a cartel to program output. The report cited historical infighting within OPEC as the likely scenario should gas quotas be imposed on the cartel members. They also noted that major gas consumers, chief among them the European Union, would oppose such a cartel and perhaps even impose trade sanctions in response.

Most of the counter arguments put forth by these journals are correct; however, they have overlooked a critical aspect of the discussion – Gazprom’s business practices. At a government to-government or corporation-to corporation level, harmonizing the agendas of such a cartel would be extremely difficult. However, the foreign investment strategy of Gazprom indicates how a voice inside many of the world’s key gas producers can be obtained without coercion. Gazprom, in addition to its monopoly of all Russian exports and the national gas pipeline system, has been buying aggressively large portions of foreign ventures. In Iran, the world’s second largest holder of proven gas reserves, Gazprom owns 30% of Phases 2 and 3 of the South Pars field project, expected to come on line in 2009.51 Despite the political difficulty of controlling such a cartel, the idea is certainly not just restricted to NATO strategists. In January 2007, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, stated that Tehran and Moscow should seriously consider forming a gas cartel. He noted (incorrectly, since the figure is about 43-44% of world reserves) that Iran and Russia together hold half of the world's total gas reserves, adding that “the two countries through mutual cooperation can establish an organization of gas exporting countries like OPEC.”52

In 2006, Russia signed deals with Algeria, eighth in the world in reserves, fifth in current production, and current provider of 16% of Europe’s natural gas imports. Gazprom and Lukoil will respectively receive shares in Algerian oil and gas fields in return for the purchase of $7.5 billion worth of Russian military equipment.53 In Venezuela, ninth in the world in terms of gas reserves, Gazprom has joint ventures in two of the government’s major gas projects – Rafael Urdaneta and Urumaco. Gazprom also has exploration joint ventures underway in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, India, Vietnam, and Libya; has feelers out to Angola; brokered a deal in late 2006 with Egypt for the sale of gas equipment in return for exploration rights;54 and reportedly is negotiating with other Latin American countries. Additionally, Gazprom has long-term gas transit contracts with Turkmenistan. Russian pipelines supply all of the Central Asian gas sold to the other former Soviet Union countries of Europe, generating revenue and additional control for Gazprom.55

Such Russian government endeavors to secure interests in gas production and transportation worldwide undercut the purported improbability of a Russian-led natural gas cartel. Russia, through its proxy Gazprom, seeks to greatly expand its worldwide influence in gas, in part through the acquisition of clout on corporate boards around the globe. This strategy is much more subtle and sophisticated than simply attempting to set production quotas, as OPEC does.

It should also be emphasized that Gazprom differs from the typical multiple hundred billion dollar corporation like ExxonMobil or British Petroleum. Half owned by the Russian government, the assistance of the executive branch enhances its ability to negotiate. For instance, in Algeria, President Putin secured deals for Russian oil and gas in exchange for arms purchases and debt cancellations.56 While the connections are not quite as obvious in Iran, the Russian government’s willingness to broker weapons deals and nuclear power equipment transfers at the same time the West refers to Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism, certainly gives Gazprom huge advantages when negotiating joint ventures in Tehran. Russia’s senior leaders often promote Russia’s industries, thereby giving Gazprom a larger voice at the boardroom table than their simple percentage of shares in a particular foreign venture would otherwise suggest.

A probable scenario involves Gazprom as a large minority stakeholder in a major LNG project in the Middle East or North Africa. With its government leverage influencing the decision of where this hypothetical consortium decides to send its LNG shipments, Russia would enjoy enhanced control over Europe’s possible sources of diversification from pipeline gas. Since the shortest routes are by far the most economical for LNG shipments, Russian partial interests in the nearest LNG providers could have dramatic effects on the ability to set the terms for Europe’s natural gas diversification.57 In this hypothetical ‘neo-cartel,’ Russia does not need its partners to agree to output ceilings. Simply agreeing to sell only to Russian-designated customers would suffice. As long as the price remained similar, Russia’s partners would find this far more palatable than the limiting of production, and therefore revenues, as with OPEC.

President Putin, in his February 2007 State of the Nation press conference, noted, “At the first stage, we agree with Iranian experts, partners and some other countries that produce and supply hydrocarbons to world markets in large volumes. We are already trying to coordinate our actions to develop markets and intend to do so in the future.”58 Two weeks later, when speaking in Doha, Qatar, Putin qualified this statement stating that, “whether we need a cartel, whether we will create such an organization, is another matter. But of course we should coordinate our activities with other producers.”59 Whether intentionally or not, Putin alluded to the most likely way that Russia could increase leverage over gas markets, by coordinating the development of markets and influencing with whom delivery contracts were signed. This would create extra leverage on a projected 2030s EU that will receive 20% of its energy from Russia in the form of natural gas.

As should be apparent, Russia already enjoys immense clout in European energy markets. This situation will only worsen in the absence of some deliberate diversification strategies on the part of the EU. This article will now transition to an analysis of Russian internal politics, which are aimed at making Gazprom a major tool of the Russian government in reasserting its lost status as a world superpower. In addition to Russia having enormous potential leverage through the control of natural gas markets, the Kremlin has adopted a methodical and calculated strategy for realizing this potential.

Chapter 2 – Gazprom and the Russian Strategy

It is commonly thought that liberalization of the Russian energy sector would help decrease the level of dependency of European energy consumers. Multiple corporate suppliers and open access to natural gas transport systems, it was argued, would bring about more favorable and competitive pricing. Access in accordance with the terms of the EU Energy Charter to the Russian Unified Gas Transportation System (UGS) for foreign producers would also increase competition. This chapter will discuss the reasons why the European Union planners would be unwise to count on any such liberalization occurring in the near future in Russia, which has no intention of ratifying the charter.

Gazprom

When examining Russian politics concerning natural gas, the focus of attention lies almost exclusively on Gazprom, the chief company in the natural gas business in Russia. Gazprom, by market capitalization, is one of the three largest corporations in the world.60 In 2005, it reverted back to a status of majority ownership by the Russian government following a 10.74% purchase of Gazprom by Rosneftegaz, which is also government controlled.61 With a 50% stake, the government exercises a deciding voice on virtually all corporate matters. Six of the seats on the company’s eleven person board of directors are even reserved for members of the Russian government.62

As the successor to the Soviet monopoly responsible for the production and distribution of natural gas (Gazprom literally translates from Russian as an abbreviation for the words gas industry), Gazprom has almost regained the status and level of control it had in 1991 when the Soviet Union dissolved and Gazprom was stripped of its pipelines and fields in the other 14 former Soviet republics. Privatization during the 1990’s saw other companies gain footholds in the Russian gas industry, however, this diversification of ownership has ended under President Vladimir Putin’s second term; with the assistance of very deliberate policies, Gazprom is regaining its monopoly status. Recall that Gazprom owns 60% of Russia’s gas reserves and complete ownership of the pipelines and pumping stations. Additionally, Gazprom owns minority interests in other independent Russian gas producers and numerous foreign consortia. Gazprom officially states that its proven gas reserves are 29.1 trillion m3, but this number includes only reserves fully-owned within Russia.63 Its stake in gas fields abroad includes trillions more cubic meters.

Gazprom extends even further, owning all or parts of 166 subsidiaries. Included among the minority ownerships are the gas distribution industries of Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Ukraine, Poland, and the Slovak republic.64 As part of the gas deal with Belarus, over the next several years, Gazprom will gain 50% of the equity of Beltransgas, the owner of Belarus’ gas distribution network. This will be in addition to the Gazprom-owned Yamal-Europe Pipeline, through which much of Russia’s gas transits across Belarus to Western Europe. Gazprom also partners with Western European corporations, giving it minority ownership in gas pipelines and storage facilities in the UK, France, Germany, and Italy. For example, in Germany, Gazprom owns 35% of Wingas, 50% of Wintershall Erdgas, 49% of Ditgaz, and 5.3% of Verbundnetz Gas.65 Gazprom is also part owner of the Blue Stream, which sends gas from Russia directly to Turkey via a pipeline running along the bottom of the Black Sea. Gazprom, in cooperation with German gas industry partners, is in the process of constructing a similar structure from Russia to Germany on the Baltic Sea floor – the Northern European Gas Pipeline (NEGP) also known as the Nord Stream. Gazprom also owns banks, hotels, and—discouragingly from the standpoint of an independent media—the major Russian newspaper Izvestia and the television channel NTV. A conglomerate with incredible power, Gazprom has the backing of the Russian government, huge assets, and, in the eve-rincreasingly controlled Russian media, its own “spin” machines.

Putin, Politics, and Gazprom

As seen in the previous section, during the last several years of Putin’s presidency, some overt steps have been taken to reassert Gazprom’s monopoly status. The motives behind Putin’s nationalization of Russia’s gas industry and other Russian strategic resources such as oil are most likely a combination of many desired results and interrelated calculations. Putin genuinely believes that these resources are too important to the needs of the state to be put in the hands of private businessmen who do not have Russian national interests in mind. As a product of the Soviet educational system, undoubtedly his perception of economics still has a centralized planning approach.

Putin made clear his views on the subject of nationalizing strategic national resources in a 1999 article, “Mineral Natural Resources in the Strategy for Development of the Russian Economy,” by highlighting the need for the state to maintain high regulatory control of resource extraction industries. In what amounts to a blueprint for his actions in steering Gazprom to the monolith that it has become, Putin stated that a key role for the state to play in the natural resource industries is the “creation of large financial-industrial groups – corporations with an interbranch profile that will be able to compete with Western transnational corporations.”66 In this article, which was published before his assumption of the Presidency, he also makes it clear that he views the government’s support for industries involved in the extraction of strategic natural resources as the means to “make Russia a great economic power with a high standard of living for the majority of the population.”67 Additionally, he justifies a turn away from privatization by stating that, “the experience of countries with a developed market economy gives us many examples of effective state intervention in the long-term project to exploit natural resources.”68

Putin gave a more sinister preview of his philosophy on the role of government in controlling strategic aspects of the economy in an article entitled “Russia at the Turn of the Millennium,” which he published December 30, 1999, the day before he assumed the role of acting President, replacing the ailing Boris Yeltsin. He stated, “Today’s situation necessitates deeper state involvement in the social and economic processes. The state must be where and as needed; freedom must be where and as required.”69 In almost unprecedented historical fashion, Putin published his manifestos on the state control of strategic resources, and then actually rose to power to implement them.

It would be incorrect to attribute totally altruistic purposes to Putin’s strategy as it is put forth in his academic writings. If the benefit of the people were truly the only motivation, then the current level of shadiness of political and business associations would not be tolerated. The composition of Russian oil and gas companies’ senior management makes it clear that politics and business are one and the same. Some prime examples include Dmitri Medvedev, First Deputy Prime Minister of the Russian Federation, who is at the same time Gazprom’s Chairman of the Board of Directors.70 There is also Alexei Miller, a former Deputy Minister of Energy of the Russian Federation and longtime Putin ally from their association in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office, who is Gazprom’s CEO. Gazprom’s corporate statements emphasize the fact that board members who are also Russian government employees have no shares or extremely limited holdings in the company.71

Despite the outwardly benign appearance of simple governmental oversight, the case of Rosneft, the Russian government-owned oil analog to Gazprom, illustrates how hundreds of millions of dollars can end up in the personal accounts of Russian officials when assets are sold in closed auctions with prices far below asset value. The most blatant and undisguised of these conflicts of interests is Igor Sechin, Chairman of the Board of Rosneft, Russia’s second largest oil company. He is officially listed on the Kremlin’s website as Deputy Chief of Staff of the Presidential Executive Office, Aide to the President. Sechin was named Chairman of the Board of Rosneft in July 2004, just months after Yukos owner Mikhail Khodorkhovsky was arrested and Yukos’ main asset, Yugansneftgaz, was sold to Rosneft at billions of dollars below their market value.72 Sechin, coincidentally, is a former army officer with service in Angola (causing many Russians to speculate that he, like Putin, is former KGB) who later worked with Putin in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office. Most alarming is that Sechin was a key government official in bringing evidence against Khodorkhovsky; his reward evidently was the position at Rosneft, a company flush with assets, for which it greatly underpaid.73

This murky relationship between politics and quasi-national ownership of businesses basically makes possible corruption at the highest levels. The nature of the government appointments to corporate boards makes this point even clearer – all the abovementioned individuals are not simply government representatives; at the same time, they are some of the most highly placed members of Putin’s administration. This blurs transparency in corporate accountability, further facilitating massive corruption. In addition to the politicians’ seats on the corporate board, the very structure of Gazprom makes it supremely conducive to accounting opacity and fraud. With 166 (listed) subsidiaries and joint ventures in dozens of countries in so many different fields, it is impossible for an auditor to verify the legitimacy of the company’s accounting.

RosUkrEnergo is a prime example of the creative ways in which money can be moved from corporate to personal accounts in the numerous Gazprom dealings. RosUkrEnergo was established in 2004 as a Swissregistered company that would act as intermediary between Gazprom and the Ukrainian state oil and gas company, Naftogaz, to broker the sale of Turkmen gas to Ukraine. RosUkrEnergo is 50% owned by Gazprom and 50% owned by two mysterious Ukrainian businessmen, Dmitry Firtash and Ivan Fursin,74 whose identities were begrudgingly given to investigators by the Austrian Raiffeisenbank, which holds the proceeds from their 50% stake. As Gazprom has sole ownership of the Russian gas pipelines and exclusive right to export gas, the logical question to pose is why was a Swiss registered corporation—earning profits of hundreds of millions per year—really needed? Clearly all the accounting for the movement of Turkmen gas through Russia could be done on the Gazprom ledgers and the sales made directly to Naftogaz. Gazprom already was the middleman, yet a subsidiary was established to introduce other middlemen.

The Ukrainian President, Viktor Yushchenko, denied on Ukrainian television knowing who the owners of the company were that supplies all his country’s imported gas.75 President Putin, however, pointedly blamed his Ukrainian counterpart for the company.

“Well, you ask Viktor Yushchenko. Gazprom has a fiftypercent stake and the Ukrainian side has a fiftypercent stake. I said to Viktor Yushchenko, ‘we would welcome it if your 50 percent is held directly by Naftogaz Ukraina.’ But this was not our decision. This was the Ukrainian side’s decision. Who the names are behind the 50percent stake held by Raiffeisenbank, I don’t know anymore than you do, and Gazprom does not know either, believe me. That is the Ukrainian half of the company and you would have to ask them. I said to Viktor Yushchenko, ‘Give Naftogaz Ukraina direct participation. If you don’t want to, let’s set up another company.’ But they did not want to. It was they who proposed that Rosukrenergo supply gas to Ukraine instead of Gazprom. We agreed. The main thing for us was the price formula.”76

This statement is strange for two reasons. First, it indicates that the Russian and Ukrainian Presidents themselves directly negotiate business deals and the formation of companies to sell gas. This admission shows the extent to which gas is used for political purposes by Russia’s leader. Second, if taken at face value, it means that Gazprom entered into a business venture involving the trade of several billion dollars worth of gas annually, but they did not even know who their partners were. In addition to this, the Chairmen of Gazprom and Naftogaz have both publicly stated that they believe the gas trade should be handled directly from one company to the other.77 Apparently, one is to believe that—despite the fact that both the governments and their nationalized gas companies were against such an entity—it was created anyway. Although impossible to prove conclusively without more evidence, one reason for the arrangement’s existence appears to be the ability to divert funds from corporate accounts to facilitate bribery at the highest levels.78

While by many accounts, Gazprom’s corporate accountability has been improving under Putin’s administration, there are still many gray areas that indicate that corruption is rampant.79 Putin and his associates probably rationalize their methods of operation: they provide the necessary leadership for strategic industry and that in turn justifies the huge amounts of money skimmed away from corporate treasuries. There is a perverse logic to the actions of the Kremlin over the last several years. By creating a nationalized gas monopoly, Russia, through Gazprom, will be able to extort higher prices from foreign consumers. At the same time, the government can continue to provide gas within Russia and to loyal partner states, such as Armenia, and to a lesser extent Belarus and Ukraine, at greatly reduced state-dictated rates. Within the framework of a Soviet upbringing, it is not hard to image that Putin and his cronies easily justify the money they take for providing such a service to the Russian people and their allies in the ‘near abroad.’ Again, Putin telegraphed this in his pre-Presidential writings when he stated that government regulation in the strategic resources sector would serve to “support and augment the country’s export potential”80 and that a primary task for the government was an economic policy that “buttresses the export possibilities of the fuel and energy complexes.”81

Ukraine – An Example

An example of how the Russian government wields its ‘energy weapon’ less blatantly than simply shutting off the tap, were the negotiations that Russia’s prime minister conducted with his Ukrainian counterpart in October 2006. According to the Russian business daily Kommersant’s sources in the Russian and Ukrainian governments, in return for a promise to keep the price of gas below $130 per 1,000 m3, Kiev agreed to four major concessions: These included (1.) postponing any referendum on NATO membership, (2.) agreeing to the terms of leaving the Russian Black Sea fleet in Sevastopol until 2017 and perhaps even extending the lease, (3.) continuing to use RosUkrEnergo as transit partner for another five years, and (4.) agreeing to receive Turkmen gas through Russia only.82

While Ukraine is an extreme case,83 it makes a vivid example of the coercive power that comes with Russian energy dependence. Ukraine’s officials evidently fear what paying full market prices for gas would do to their economy and are therefore willing to make a variety of concessions that hand over a great deal of their sovereignty to Russia, to the extent that even decisions on collective security and stationing of foreign troops become secondary. Also, given the involvement of RosUkrEnergo in these terms, corruption may play a large part in the concessions as well.84 This aspect should not be underestimated, as the ability to corrupt foreign officials is an extremely valuable tool, in addition to just plain coercion. In the case of Russian Ukrainian gas trade, it is only circumstantial evidence, but all the known facts point to bribery being a weapon in the arsenal of Russian energy foreign policy.

Permission to Monopolize the Market

Before continuing with an analysis of the motivations behind the nationalization and monopolization of Gazprom, it is useful to examine the steps that Russian government has taken to solidify the company’s position. These actions in themselves make it clear that the Russian government has strategic intent for its megacorporation, which some analysts have sardonically dubbed “Russia, Inc.” and led others to quip that “if the Kremlin had a stock exchange listing, Gazprom would be it.”85

In July 2006, Putin signed into law legislation passed by the Federation Council and State Duma concerning the right to sell Russian natural gas abroad. The law specifically states that the “exclusive right to the export of natural gas belongs to that organization which owns the unified system of gas supply or its subsidiary company ….”86 The passage of this law gave Gazprom not only a physical monopoly on the export of gas because of its ownership of the UGS, but also a legal sanctioning of that monopoly.

The coup de grace for any chance for a return to liberalization of the gas sector occurred in January 2007, when the Moscow Arbitrage Court ruled that Gazprom may purchase other domestic gas production assets, contrary to an earlier ruling by the Russian Federal Anti Monopoly Service prohibiting such a move.87 This ruling will make possible the return of Russia’s natural gas sector to absolute government control under the auspices of Gazprom, which already directly owns 60% of Russian gas reserves. It gives Gazprom free reign to buy out the few remaining natural gas companies that are not government owned, including Novatek, Itera, Nortgaz, and Rospan International.88 Gazprom already owns 19.9% of Novatek, Russia’s second largest gas producer, in a deal that was brokered in spite of the Anti-Monopoly Service’s prior ruling. Gazprom has also taken a controlling interest in several of Itera’s subsidiaries.89

As one analyst correctly pointed out, this will not actually affect competition within the Russian gas industry since there is no competition; it will simply put more reserves under Gazprom’s control and increase their price-setting capabilities abroad.90 Because the Russian government dictates the terms of domestic sale of gas for independent producers, there is no price competition. By sanction of the July 2006 law, only Gazprom is allowed to sell gas to foreign markets, where prices of $230 – 250 per thousand m3 are normal rates for long-term contracts. This leaves the independents to sell only to internal Russian markets at greatly reduced prices ranging from $26-$49 per thousand m3.91 As Gazprom owns all the pipelines in Russia, the independents must pay Gazprom transit fees to even market their gas at the vastly reduced internal rates. These two levers of control—pricing and pipelines, plus the aid of governmental ministries and the courts—will make the job of finishing Gazprom’s consolidation of the natural gas industry within Russia easy work.

It remains to be seen if a controlling stake in all the remaining independent gas companies is the ultimate goal of the Russian government, since keeping around some independent producers ultimately will not affect gas exports and leaves room for foreign investment outside of Gazprom. Regardless of the ultimate configuration of gas producers, any roadblocks to such an absolute monopoly have been removed and the government has achieved its desired goal: total control of all aspects of natural gas exports from Russia and the capability to increase Gazprom’s internal portfolio if the need arises.

Sakhalin 2

Nowhere is the deliberate and calculated effort of the Russian government to regain control over its natural gas assets and increase Gazprom’s influence in the gas markets more evident than in the Sakhalin 2 negotiations that transpired in the latter half of 2006. The Sakhalin 2 Energy Project was originally established as a Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) between the Russian government and the AngloDutch consortium Royal Dutch Shell and Japanese minority partners Mitsui and Mitsubishi Corporations. The purpose was to develop the immense oil and gas reserves in the deep ocean waters off the coast of Sakhalin Island just north of Japan. In the 1990’s, the Russian hydrocarbon industries were extremely reliant on foreign investment and technology due to both sustained economic recession and a general inexperience in exploration in more difficult conditions such as deep oceans. Russia therefore gave favorable conditions to these three investors.

The Sakhalin LNG shipments that were slated to begin in late 2007 or 2008 are crucial to Japan, which uses 100% LNG for its natural gas. The terms of the original PSA had the Russian government receiving profits only after the Shell Japanese venture recouped its investment. Sakhalin 2 is estimated at having reserves of 498 billion m3 of gas92 that could fetch over $100 billion at current prices. As the cost of the venture had doubled by 2006, the Russian government was apparently going to have to wait until considerable revenues were generated from the project before they would receive any monies. At that point, the Russian Ministry of the Environment, Prirodnadzor, stepped in and leveled numerous environmental charges against the Sakhalin Energy Investment Corporation (SEIC), basically bringing the project to a halt.

In December 2006, Gazprom, with the help of considerable pressure from these governmental environmental regulators, was able to obtain a 50% plus one share ownership of SEIC for $7.45 billion, significantly below the market value of the controlling portion of the company – minimum estimates had been 11 billion dollars.93 Under the terms of the agreement, Shell, Mitsui, and Mitsubishi all relented and agreed to proportionately dilute their ownership in return for the cash payment, thereby relinquishing controlling share of SEIC to Gazprom. When specifically asked if the Russian government made the environmental allegations to gain control of the project, the Japanese Minister of Trade, Economy, and Industry, Akira Amari, said “I feel that way but I cannot assert it in my position as trade minister.”94

Putin’s comment on the signing of the deal was less than sincere and a clear attempt at deflecting any criticism that the Kremlin had orchestrated the whole takeover, “Gazprom decided today to take part in the joint Sakhalin2 project. This is a corporate decision. The Russian government was informed about it and we have no objections to it, we welcome it.” He added, “the Russian government and investors are interested in the implementation of this project .... Once again, I want to stress that we will do everything to carry this project through.”95 Considering Dmitri Medvedev’s dual hat role as Deputy Prime Minister and Gazprom Chairman of the Board and the charges leveled by the Russian Ministry of the Interior, Putin was audacious to spin the situation as if it were a business decision, in which the Russian government played no part. In actuality, the takeover was calculated and planned by Putin and his ministers and is in complete accord with Putin’s own 1999 musings on the need to nationalize strategic resources.

Kovykta

History is repeating itself as the Kovykta project is in jeopardy of having its license revoked. This gas field in Eastern Siberia is owned by RUSIA Petroleum, the TKNBP consortium of British Petroleum in conjunction with Interros, a large Russian holding company, and the Irkutsk Regional Government.96 In this instance, the challenging agent of the government is Rosnedra, the Russian Federal Agency for Subsoil Use. The original PSA for the development of the Kovykta fields called for 9 billion m3 per year to be supplied to the Irkutsk Region by 2006.97 The agreement was written a decade ago, when gas demands for the region were envisioned to be much higher. For several reasons, the project is producing far less than the amount stipulated in the licensing agreement granted to RUSIA Petroleum. These reasons are directly attributable to deliberate actions of the Russian government. Demand is low because much of the region still does not have distribution to households, part of the Russian ‘gasification’ project. While the Kovykta project could produce much more gas, Gazprom controls all exports and has blocked any such sales.98 Therefore, the gas must be sold domestically, leaving the consortium with the unlikely option to sell its gas on local markets at rates that are far below market prices or literally burn it off in order to meet the quota.

In a clear sign that the highest levels of the Russian government are pulling all the strings in this latest transaction, the head of Rosnedra, Anatoly Ledovskikh, stated that the original terms of the agreement could not be amended with the current owners, but at the same time he implied that the government would amend the terms with a new owner and not be in violation of the law.99 In the same interview, he dodged the question of why new terms simply could not be arranged with the current owners.

Since the start of the Sakhalin 2 environmental issues, it became apparent to the Kovykta owners that they were going to be eventually muscled out by the very government and policies that prohibit them from profitably selling the gas. In an attempt to preserve its investment to date, the consortium owners have been in talks with Gazprom since December 2006; it is almost certain that some sort of arrangement that cedes 50% ownership will be struck. Rosnedra has given RUSIA Petroleum until May 2007 to be in compliance with the volume of production terms. As the Kovykta field is rated at 1.9 trillion m3 of reserves and is considered by many to be the critical asset for future deliveries to the Chinese market,100 a deal amenable to the Russian government, which at the same time preserves some perspective of profitability for foreign investors, will likely be signed soon with Gazprom.101 As with Sakhalin 2 and the Yukos affair in 2003, the Russian government will almost certainly orchestrate the required moves to reobtain these highly desired resources.

Gazprom’s Distribution Portfolio and the Energy Charter

The methodical steps the Russian government has overtly and unabashedly taken to regain total control of the gas sector should be fairly apparent and convincing to the reader. The question remains, to what end? The absolute monopolization of the gas industry is clearly not in the best interest of the consumer – even postSoviet Russian leaders know that monopolies are bad for pricing, which is why a Russian Federation AntiMonopoly Service was even created. In this instance though, the concern is not the internal market, but rather gaining the ability to manipulate the export market. Numerous Russian gas corporations vying for European customers would obviously be beneficial for the consumer, but a unified Gazprom, staunchly supported by the Russian executive branch, will not only have the ability to set prices based on its monopolistic position, but can do so with the backing of significant political might.

Gazprom’s downstream ownership in the gas distribution networks is a critical part of the strategy to dominate the European market. As energy analyst Roman Kupchinsky aptly described Gazprom’s distribution acquisitions, “He who controls the pipeline therefore controls the buyer.”102 Estimates are that Gazprom has spent $2.6 billion in recent years on Western European gas distribution assets with the intent of increasing its market power all the way down to the consumer.103 As pointed out previously, Gazprom has a minority interest in virtually every European country’s gas distribution network. An increasingly apparent Gazprom strategy is attracting investment and technology to permit limited foreign participation in Russian gas fields, but only in return for ownership in distribution, transportation, and refinery assets in Europe.104

The acquisition of foreign gas infrastructures complements Russia’s refusal to ratify the Energy Charter. The European Energy Charter is an extremely vague, 250 page legal document that has numerous interpretations. Article 7 states that a signatory to the charter:

“…shall take the necessary measures to facilitate the Transit of Energy Materials and Products consistent with the principle of freedom of transit and without distinction as to the origin, destination, or ownership of such Energy Materials and Products or discrimination as to pricing on the basis of such distinctions, and without imposing any unreasonable delays, restrictions or charges.”105

This section has been generally interpreted that (germane to this discussion) pipelines should be open to access by any producer’s gas, as long as that access does not interfere with, or preclude the capacity of, the pipeline to transit the owning country’s gas.106 Without even listing Moscow’s specific objections to the charter, on the most fundamental level it is apparent that it is not compatible with domestic legislation. Russian law currently does not allow even independent Russian companies to export gas on the UGS, let alone a foreign entity.

President Putin articulated the government’s principal objections to the Charter in September 2006, however, and they are worth noting. His primary concern is that letting intermediaries use the pipelines would not lower prices, but allow someone other than Russia to pocket the profits. Second is that such access would have to be an equitable exchange for Russia; its European partners have no energy resources that Russia needs, so what could be gained in return? Putin also tied the Energy Charter to granting Russia access to advanced technologies and nuclear fuels, which are currently restricted by most of the Western partners for sale to Russia.107

Beyond the official reasons, another motivation is evident: Russia wishes to monopolize the transit of natural gas from Central Asia. As will be discussed, Central Asian gas presents one of the best alternate sources for European consumers. Currently, all that gas transits to Europe via Russia’s UGS. Abiding by the spirit of the Energy Charter would open that transit business to an intermediary other than Gazprom. Granted, the intermediary would still have to pay ‘reasonable’108 transit fees for the usage of the network, but the leverage that Russia currently exerts on both Central Asian governments and the consumers of their gas would be lost. For all these reasons, it is pointless for the EU to expect Russia to agree to the terms of the Energy Charter. With the 10year “Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between Russia and the EU” expiring in 2007,109 barring some unforeseen concession on behalf of the EU, the Energy Charter will be a continuing point of contention within the EU-Russia Energy Dialogue.

Russian Imperial Thinking

Clearly, nationalization of the gas extraction and distribution industries is deliberate and carefully planned. Putin’s academic mentor and doctoral dissertation sponsor, Vladimir Litvinenko, Rector of the St. Petersburg Mining Institute (and a recent addition to the Energy Policy Committee), summed up his protégé’s philosophy on the matter quite succinctly: “In the specific circumstances the world finds itself in today, the most important resources are hydrocarbons. They are the main instrument in our hands – particularly in Putin’s – and our strongest argument in geopolitics.”110 Many Western analysts agree with this assessment, as evidenced by this statement from the Economist on Putin’s rationale for establishing a gas export monopoly, “it guarantees the Kremlin’s control over what, with the possible exception of nuclear weapons, has become Russia’s most powerful foreign-policy tool, and its best hope of regaining lost clout.”111

Lost clout is most likely the overriding motivation behind these machinations – the re nationalization of the gas and oil industries with the simultaneous reduction of foreign ownership. Russia lost incredible prestige and power with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Whether the Soviet Union stood on the morally right side of the Cold War still seems irrelevant to most Russians; they are still fiercely proud of the superpower status they once held. Many are ambivalent about the nature of the Soviet regime, but not about the prestige that it brought Russia in world affairs. A recent poll indicates that 35% of Russians would even like to see a return to the Soviet system.112 Regaining superpower status seems paramount amongst the Russian political elite.

Putin summed up this way of thinking in his 1999 treatise prior to assuming the presidency:

“Russia was and will remain a great power. It is preconditioned by the inseparable characteristics of its geopolitical, economic, and cultural existence. They determined the mentality of Russians and the policy of the government throughout the history of Russia and they cannot but do so at present.”113

In a recent round-table discussion of Russian foreign policy decision makers, this was the underlying theme as expressed by Pavel Ipatov, Governor of the Saratov region, “Our country is focused on resolving the problems on which its economic and social progress depend, and restoring its natural historical role of great nation.”114 Although it is the author’s emphasis on the word natural, it is important to understand that Russian elites see their country in this very way; because of its unique position as neither West nor East, as well as its history, people, and resources, Russia necessarily must be a great power.

Opinion polls confirm this view; a full 75% of Russians believe that “their country is a Eurasian state with its own path of development,” while only 10 percent think it “part of the West, with a vocation to move closer to Europe and the United States.”115 Particularly alarming is the prevalent popular notion (45% of Russian’s polled) that “the European Union threatens Russia’s financial and economic independence, would impose its foreign culture on Russia, and is a menace to Russia’s political independence.”116 This sentiment is especially troubling in the context of the thesis that there is a calculated effort to exert political leverage over the EU via gas.

In general terms, Russia sees several methods for regaining its lost superpower status and rebuilding the country’s military might. While it is unclear how the revenues from hydrocarbon sales will be distributed, given that 25% of Russian tax revenue comes from Gazprom,117 the company’s profitability will have a large affect of the government’s ability to spend on defense. Although it is unlikely that any near-term Russian administration would commit the folly of totally undermining the economy with military spending as their Soviet predecessors did,118 the recent proclamation that the Russian government will spend $190 billion between now and 2015 for weapons modernization indicates that rebuilding powerful armed forces is at least a top agenda item.119

It would be too simplistic; however, to state that the Kremlin’s overarching plan is to build a new army based on its oil and gas dollars. Putin expressed his thoughts on the very subject:

“In the present world the might of a country is manifested more in its ability to be the leader in creating and using advanced technologies, ensuring a high level of the people’s well-being, reliably protecting its security and upholding its interests in the international arena, than its military strength.”120

In Putin’s vision of a resurgent Russia playing the role of great power, gas and oil money will play a pivotal role in financing not only the military, but also social programs and infrastructure. He also views gas as a key instrument for achieving Russian foreign policy goals, particularly in Europe.

Thus, Russian leadership is purposefully rebuilding a monopoly in the gas sector under the guise of Gazprom. Its intents are multiple; but chief among them is a belief that such strategic resources cannot be left in the hands of businessmen who will not look after the national interest. Simultaneously, the re-nationalization of the hydrocarbon industries creates the ability to amass personal power, avenues for diverting funds for personal wealth, and even the means for controlling foreign officials, which makes it all the more unlikely that foreseeable administrations121 will relinquish this increased government control without severe provocation. More important to EU and other consumers of Russian energy, these policies are aimed at increasing the Russian state’s economic instrument of power and, more specifically, to be able to set prices in regional gas markets and obtain increased political leverage from the control of this hugely important energy source.

Regardless of whether or not Russia will deliberately try to leverage the political decisions of EU leaders over the longer term through the might of its gas (although it appears that is in fact the very outcome planned for by Russian leaders), it would be unwise for the EU to rely upon any one source for over 30% of its energy.122 Given the unreliable nature of the source, Europe’s politicians may find they are beholden to Russia. Even worse, they could become the key factor in literally and figuratively arming a clearly resurgent Russia. Rather than telling their constituents they may have to ration heat or electricity in winter, it would be much easier to simply turn a blind eye to undesired Russian behavior, or as in the case of Ukraine, succumb to Russian pressure. The security implications of this Russian influence are profound.

Chapter 3 – Counter Arguments

It seems clear that Russia’s dominant position in European gas markets presents a serious threat to the political sovereignty of the EU states and, even more so, to the non-EU aligned former Soviet states entirely dependent on Russian gas. However, several arguments that counter this thesis warrant discussion, as they could mitigate the severity of Russia’s ability to assert control in Europe via natural gas – its leading ‘energy weapon.’ Of the counterarguments, four stand out as mitigating scenarios.

China – Not a Desirable Partner

The first scenario has been proposed by Vladimir Milov, President of the Institute of Energy Policy in Russia, the first Russian independent think tank dedicated specifically to energy policy issues. His basic thesis is that China is not the highly desirable business partner in the gas markets that the Kremlin neocons123 assume. One key feature of this neocon vision of the future is a Russia that turns away from its current position, in which 99% of natural gas exports go to greater Europe,124 leaving Europe with an energy shortage. Instead, Russia will become a major energy supplier to China, creating an alternate to the geopolitical hegemony of the West.125

Milov argues, however, that Russia’s ‘economic breakthrough’ in the East is not nearly as likely as Kremlin planners would hope. He points to three problems confronting a major Russian entry into Chinese gas markets.126 First is the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) desire to retain its own energy independence. In the case of gas, Milov asserts that midterm demands for electricity can be met with the increased hydroelectric, nuclear, and coal-burning power generation. He also argues that energy negotiations with China always include price disputes, with the PRC willing to pay only about $40 per 1,000 m3, far below a “break even” price for Russian deliveries from their fields in Kovytka in Eastern Siberia. In negotiations with Russia, the PRC has stated they will use their own coal rather than pay higher prices. Thirdly, Milov points to the geographical problem presented by Russian gas deliveries: the highest demand areas are on China’s southeastern coast, which are the greatest distance from Russia’s fields. He asserts that China will meet increasing gas needs in its industrial southeast with LNG terminals.127

These arguments are well-reasoned and, if true, a failure of Russia to partner with China would diminish Russia’s leverage on European gas markets. If it were to not open routes to China, other than its proposed LNG exports to Japan and South Korea from the Sakhalin Island projects and LNG from the Shtokman field to the United States, Russia would be stuck exclusively with pipeline deliveries to Europe. In such a case, ‘mutual dependence’ would still clearly favor Russia as the supplier, but the overall lessened demand would diminish Russia’s ability to set prices.128

Milov’s points are based on assumptions about which he gives little detail and contingencies that are clearly unpredictable. First, assuming that the PRC’s government aspires to maintain its 9% average annual GDP growth rates of the last decade,129 it will correspondingly need to increase its energy consumption. Continuing to increase hydroelectric power generation is possible with projects such as the Three Gorges Dam project on the Yangtze River expected to be totally finished in 2013, but dam construction can take an extremely long time130 and dams can have radical side affects on the landscape, especially with the diversion of large rivers. Most importantly, China suffers from droughts and floods, with droughts in particular bringing unpredictability in the level of hydroelectric power generation. China may look to gas to level these peaks and valleys in electricity production.

Milov points to nuclear power as an alternative source, but the economics of nuclear power may make Russian gas at $230-250 per 1000 m3 seem attractive. Recalling figures cited earlier, even paying these prices for imported gas, gas-powered electricity production in Western Europe is still slightly less expensive than nuclear power. China may therefore look to diversify its power production with imported gas, which is cheaper and less risky than nuclear power.

China has large coal reserves,131 but coal power generation has major drawbacks that will most likely prevent coal from becoming an even larger percentage of China’s future electric power generation mix. China already depends upon coal for three-quarters of its power generation. Reserves will likely last for several hundred years, but China would have to greatly expand its mining capacity to meet future needs with coal alone. While China is not a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol on CO2 emission reduction, the real question is to what extent the PRC government is willing to ruin the country’s environment for the sake of increased growth.

As critical as any intra-governmental decision would be, the external pressure under which China would presumably find itself from its more environmentally-minded trading partners would be formidable. Rampant pollution created by coal burning stations would affect global emissions levels and would not sit well, particularly with the EU, which has made strong commitments to controlling global warming and likely will not accept such behavior. During the course of the EU’s Energy Summit in March 2007, German Chancellor Angela Merkel made it clear that a future agenda item for the G8 would be to bring pressure to bear on the US and China to reduce coal burning in order to cut greenhouse gas emissions.132 Chinese attempts to maintain energy growth through coal, at a similar or even higher percentage of the overall energy mix, will meet with a strong reaction. In a worst-case scenario, China could find trade restrictions and embargoes placed on it if it were to intensify its coal-based energy strategy, especially as more evidence comes in that global warming is a phenomenon well underway.

The suggestion that LNG will be the predominant source of natural gas in southeastern China, where demand will be the highest, seems to have no support other than geography. It makes the bold assumption that China will be able to sign LNG contracts that are more economical than pipeline gas from Russia. As already noted, a percentage of LNG is lost in transit due to vaporization, therefore the closer the supplier, the less gas is lost. Three countries that rely exclusively on LNG are Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan; all are in extremely close proximity to China and therefore all are logical competitors for the same sources of LNG. The United States and India also stand to be big bidders for LNG from the Pacific region.133

Given at least five major customers for Pacific LNG, there is no reason to assume that LNG will be cheaper than Russian pipeline gas. Recent examples of Spain outbidding the United States for long-term contracts indicate how the LNG market has not yet developed enough supply to be a buyer’s market.134 Also, given that the Sakhalin Island projects are likely to be one of the biggest suppliers of LNG in the Pacific, it does not seem logical that Russia would sell LNG at favorable prices to China when it could meet Chinese demand with pipeline gas from Kovykta and use the Sakhalin LNG to sate other customers such as Japan and the US. Although geography makes an interesting case for LNG being the preferred solution on Chinese markets, when looking at all the factors, Russian pipeline gas will almost certainly be more affordable and attainable.

For all these reasons, the PRC will most likely pursue an energy strategy to diversify from excessive coal use to a mix with a more balanced use of electricity generation from pipeline gas, nuclear, renewable (in the form of hydro-power), and perhaps LNG, but without an over-reliance on any one of them. Given all these factors, contrary to Milov’s pessimism, there is a high probability that Russia will establish a gas market to China, creating an unfavorable situation for the EU and greater Europe, in which Russia has pipeline markets to both the west and east. Alexander Medvedev, General Director of Gazprom’s Gazexport, recently reaffirmed this optimism by stating, “We regard China as not only the most promising export market but also s a partner in building gas transportation projects and in joint marketing of gas.”135

A New Energy Source

A second scenario is the development of a new energy source that would make other forms obsolete. In the domain of natural gas markets and its use in electric power generation, the only ‘magic bullet’ on the foreseeable horizon is fusion power. The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project will not likely produce a working reactor for 30 years (if the technology even works) and then the process of building reactors based upon the prototype will take at least another decade.136 Realistically, fusion power will not provide a commercially available alternate form of electric power generation until 2045-2050. The bottom line is that a yet undeveloped energy source is not something upon which to base planning.

Although Russian analysts themselves express concern that their ‘energy holiday’ may last only a few more decades, EU energy planners cannot afford to base their decisions on such optimistic visions of the future. Russian neoconservatives view optimistic new energy source scenarios as the reason to dominate markets now, while prices for hydrocarbons are high. Mikhail Delyagin, of Russia’s Institute of Global Studies, proposed an “Energy Doctrine of Russia,” in which he outlines a strategy to maximize Russian dominance in energy markets while the opportunity exists.137 Although Delyagin’s vision can only be described as hyper-conservative and ultra-nationalistic, his strategy is similar to the one the Russian government is apparently pursuing. The critical point to glean from Delyagin, and apparently the current Kremlin perspective, is that the time is now to rebuild Russia’s superpower status, as technological advances could render their hydrocarbon treasures significantly less valuable. In this way, the alternate energy source thesis argues doubly for Europe’s need to diversify from Russian gas; it is a future that cannot be counted upon for a fallback position. More importantly, Russia is already considering it as a contingency and acting now to maximize influence and profits in Europe.

Control of Central Asian Gas Supplies to Europe