Strategic Culture and Russia’s “Pivot to the East:” Russia, China, and “Greater Eurasia”

Executive Summary

- Russia’s strategic culture has been primarily shaped by its troubled relationship with Europe and the West, but relations with Asia have also had a profound impact on Russian strategic thought. Historically, attempts to reorient Russian policy toward Asia have often sought to compensate for worsening relations with the West, but have frequently ended in failure.

- President Putin’s current “Pivot to the East” has had important successes, but has failed to resolve a long-term strategic challenge for Russia—how to manage its relations with China without becoming a junior, dependent partner.

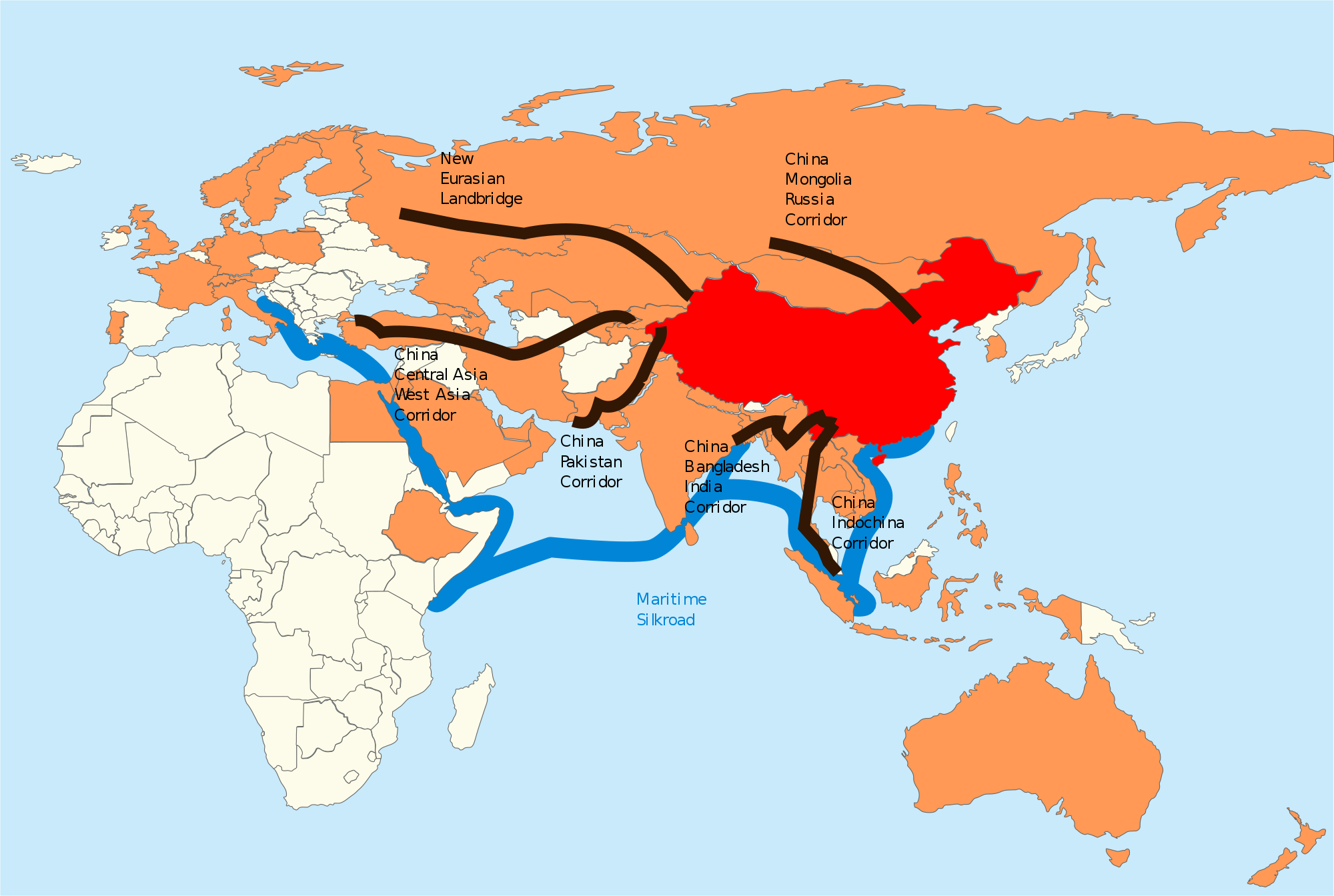

- In response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which threaten to dominate the Eurasian continent, Russia has proposed a “Greater Eurasian Partnership,” which promotes a Russian-led vision of Eurasian integration, in cooperation with a rising China.

- The “Greater Eurasia” idea has little economic or institutional backing, and exists largely at a rhetorical level. Moreover, it reproduces many of the historical challenges of Russia’s Asia policy: it is still largely informed by Russia’s problematic relations with the West, promoting Greater Eurasia as an emerging anti-Western bloc. It highlights important differences with China’s vision for a new Eurasian order.

- Critics of the “Greater Eurasia” project argue that Russia should avoid dependence on China by maintaining an “equidistant” position between East and West, a strategic turn dubbed “geopolitical loneliness.”

Russia and Asia: A Troubled History

Putin’s “Pivot to the East,” announced during his 2012 election campaign, is far from Russia’s first attempt to reorient its foreign policy toward Asia. Historically, Russia’s strategic culture has been shaped by the tension between its relationship with Europe and numerous attempts to balance its European orientation with new initiatives in Asia.1 At the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, Russia became the first European country to sign a treaty with China, as the Russian state opened up new trade routes through Siberia. Its later expansion was less peaceful: The Tsarist Empire seized more than 665,000 square miles of territory from China in Siberia, Central Asia, and the Far East between 1858 and 1864.2 In the 1890s, the construction of the Trans-Siberian railway opened up the Russian Far East to settlement, trade, and military deployment, but also involved Russia more deeply in East Asian geopolitics. Yet this late Tsarist “pivot” to Asia ended in ignominy, in the first defeat of a major European power by an Asian state in the Russo-Japanese war of 1905.

After 1917, the Soviets also turned to the East, disappointed by the failure of the European working class to rise in support of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia. “Let us turn our faces towards Asia,” said Lenin, aiming to “set the East ablaze” in revolution.3 The attempt to export revolution was largely a failure, and Stalin refocused attention on the domestic front, with his “socialism in one country” policy, which sought to strengthen socialism within the Soviet Union. In the 1940s, however, Stalin played a major role in the Chinese Communist Party’s victory, and the two Communist states forged a seemingly invincible alliance in the early 1950s. Yet in the 1960s, this pivot also collapsed over ideological differences and competition for leadership of the Communist movement. In 1969 the two states almost went to war with each other over a border dispute. Good relations were not restored until the 1980s when a speech in 1986 by Mikhail Gorbachev set out a vision for a new Soviet policy towards East Asia. Moscow’s lack of commitment and internal turmoil led to the collapse of this initiative within a few years, and with it, the Soviet state.4.

Post-Soviet Russia followed similar pattern of oscillations between enthusiasm and indifference in its policy toward its eastern neighbors. Relations with China, South Korea, and Japan all improved markedly in the 1990s, but the dispute over ownership of the Russian-controlled Kurile Islands ensured that a long-awaited breakthrough in relations with Japan did not occur. Instead, Russia’s policy in East Asia became increasingly dominated by its bilateral ties with China. China and Russia became “strategic partners” in 1996, in accordance with then-foreign minister Yevgeny Primakov’s commitment to a more balanced Russian foreign policy. In 2001, Russia signed a Treaty of Good-Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation with China, and longstanding border disputes were resolved in 2005. Progress on trade and economic integration was slower—China was more interested in close ties with the United States, and Russia was cautious about Chinese investment in strategic sectors.

Russia’s latest “pivot to the East” began with a rhetorical flourish at the beginning of Vladimir Putin’s third presidential term (2012–2018).5 It was accelerated by the downturn in relations with the West after Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula from Ukrainian control in March 2014. This new policy orientation promised new initiatives in three key directions: more economic development in Russia’s Far Eastern regions, reviving ties with former Soviet republics through Eurasian integration, and forging a closer political alignment with China and East Asian countries.

The domestic agenda—development in the Russian Far East—has been the least successful of these initiatives. In December 2013, Putin declared that “Russia’s reorientation toward the Pacific Ocean and the dynamic development in all our eastern territories are our priority for the whole 21st century."6 In reality, political, economic, and cultural life remains centered in Moscow. A highly centralized political and fiscal system actively discourages local and regional initiatives. Business and taxes flow into the center, rather than remaining in the regions, and government spending reflects this centralization. According to one source, as much as seventy percent of transport construction in Russia happens within fifty kilometers of Moscow.7 One critic, Viktor Larin, argues that whatever new slogans about an eastern “pivot” are dreamed up in Moscow, “on the shores of the Pacific Ocean they are increasingly received as just another experiment of Kremlin dreamers.8

The second goal, Eurasian integration, has also faced challenges. The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) began functioning in 2015 as a customs union consisting of the Kyrgyz Republic, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Russia, and Belarus. Efforts to convince Ukraine to join the bloc ended in political turmoil and conflict. The remaining members of the EAEU have been embroiled in trade wars and disagreements over sanctions regimes. Other states show little inclination to join. Even one of the strongest backers of Eurasian integration, Sergei Karaganov, a professor and dean at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, admits that there is “no sense of success in societies or in elites,” and instead the EAEU faces a “flood of criticism.”9 The EAEU should not be written off: its capacity to set external tariffs on goods from China and elsewhere entering the EAEU does strengthen Russia’s influence in Central Asia, but it is primarily a geopolitical, not an economic initiative.

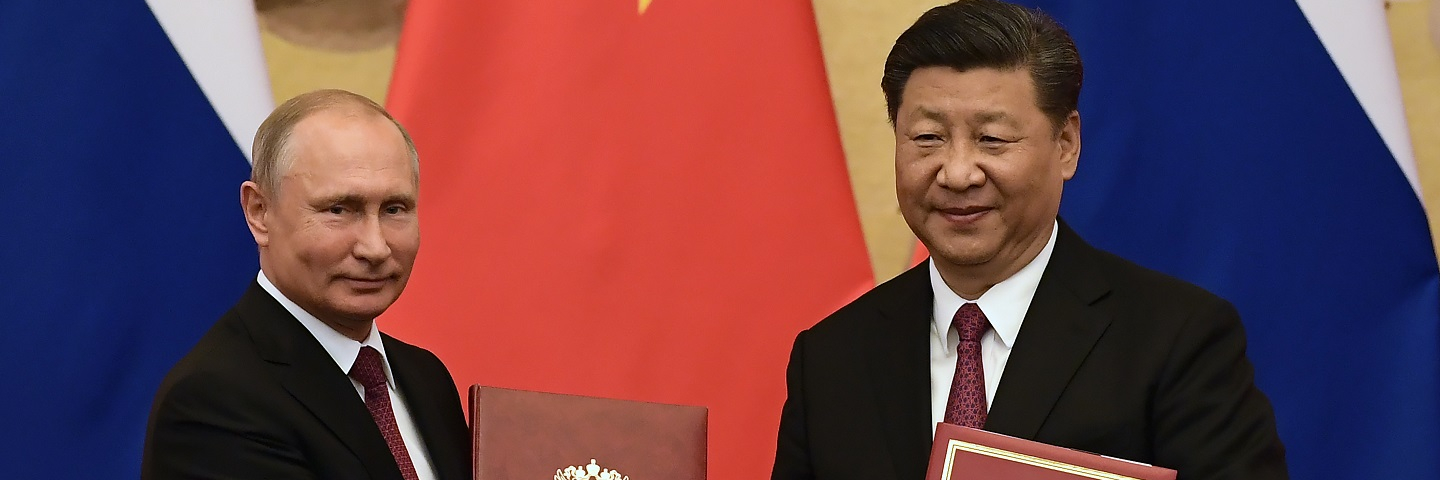

The third goal of the pivot—Russia’s growing relationship with China—has been more successful. Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping have presided over a sharp upturn in ties, partly based on a strong personal relationship between the two leaders. Chinese investment in Russia has been disappointing, but trade has still boomed to $108 billion in 2018 up from just $21 billion in 2005. The two sides are forming a strategic energy partnership: Russia is now China’s biggest source of crude oil, China has invested in two major LNG plants in the Russian Arctic, and the Power of Siberia pipeline delivering Russian gas to China will come on stream later this year.10 China also remains a key market for Russian arms sales. Russia has sold China some of its most advanced equipment, including SU-35 fighter jets and S-400 surface-to-air missile systems.11 Some experts suggest Russia has a short window—a decade or less—before China’s domestic arms industry develops a similar level of technological innovation and Russia begins to lose out to China’s domestic producers.12.Direct military ties are also growing: at the Vostok military exercises in September 2018 in the Russian Eastern Military District, a 3,500-strong contingent from the People’s Liberation Army participated for the first time.13

Perhaps most significant is the close diplomatic relationship between the two countries. At the United Nations and in other bodies, Russia and China do not always agree, but they never oppose each other in public. Often their diplomats work together to shape debates and influence outcomes. They are no longer only rule-takers, but are beginning to shape international norms and structures of global governance, promoting the principle of state sovereignty and downplaying such liberal norms as human rights, the responsibility to protect, or democracy promotion.

Yet Russia continues to struggle to find a workable framework within which it can manage China’s rise. Despite Russia’s close relationship with Beijing, it has been cautious about China’s multilateral initiatives and nervous about China’s expansion into its sphere of influence. Russia effectively blocked efforts to turn the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) into an economic club or free trade zone, which would have strengthened China’s influence in Central Asia. When China announced the formation of the Asian International Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2014, Russia initially balked at joining.14 Despite President Putin’s star role at successive conferences on the Belt and Road Initiative in Beijing, Russia has still not agreed to membership in the BRI. As China continues to rise, Russia’s international role remains limited by its underwhelming economic growth, and it risks ending up in a difficult position as China’s junior partner.

Greater Eurasia

Since the 19th century, Russia had been the dominant partner in relations with China, but now it is increasingly the other way round. Geographic frameworks within Russia’s strategic culture have struggled to accommodate this new reality of a rising China. The idea of a “Russian World,” which came to prominence in 2013-14, viewed Russia as the center of a Russian-speaking sphere of influence, but had nothing to say about its relations with Asia. There was more potential in the idea of Eurasia, a movement that rejected Russia’s European heritage and asserted an alternative identity and geopolitical destiny in the East.

The original Eurasianist movement, founded in the 1920s by Russian intellectuals in exile, used the term “Eurasia” to describe the vast geographical expanse stretching from Eastern Europe to the borders of the Chinese empire.15 The idea of Russia as a great power at the heart of this world in between Europe and Asia has been highly influential in post-Soviet Russian strategic thinking. Yet Eurasianism failed to offer a clear strategic answer to the challenge of a rising China. In traditional Eurasianist thinking, Eurasia was a civilizational and geopolitical bloc sharply distinguished from—and often opposed to—the Confucian-Buddhist civilizational space of China.16 Many Eurasianist ideas reinforced traditional Russian suspicions of China, views that had been intensified during the Sino-Soviet split.

In the mid-2010s, foreign policy thinkers in Moscow tried to address this challenge with a novel concept of “Greater Eurasia,” an idea described as Russia’s first genuine strategic concept since the end of the Soviet Union.17 It first emerged in 2015 among a group of Russian foreign policy thinkers in the pro-Kremlin Valdai Club, led by Sergei Karaganov, Timofey Bordachev, and other scholars. Karaganov and his colleagues argued that the idea of a “China threat” was an invented notion from the Soviet period, encouraged in later years by the United States. Instead, China should be a key ally for Russia in the development of a new “greater Eurasian community.” Russia should embrace new Chinese investment in transport and other infrastructure projects, using the Belt and Road Initiative as a way of shifting the focus of Russia’s development from the European part of Russia to Siberia and the Far East.

The term quickly gained traction in official circles. Sergei Naryshkin, then Speaker of the State Duma, began talking of a “Greater Eurasia” stretching from Murmansk to Shanghai.18 In June 2016, Putin used the term in a discussion at the plenary session of the Petersburg International Economic Forum, talking about “the creation of a greater Eurasian partnership with the participation of the Eurasian Economic Community, and also countries, with which we have close relations: China, India, Pakistan, and Iran."19 At the May 2017 International Forum, “One-Belt, One-Road” in Beijing, Putin argued that “One Belt, One Road, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), are capable of becoming the basis for the formation of a Greater Eurasian partnership."20 He returned to the idea at the 2019 Belt and Road Initiative meeting, claiming that the “the PRC president’s Belt and Road initiative echoes the Russian idea of creating a “Greater Eurasian Partnership,” which would involve an “integration of integrations” or “a close linking of various ongoing bilateral and multilateral integration processes in Eurasia.21

In diplomatic statements, Greater Eurasia has become a useful framing device, in which Russia is portrayed as an equal partner with China, and the Belt and Road Initiative and the EAEU are presented as integration projects of equivalent significance, but diplomatic rhetoric can hardly disguise the growing divide between China’s $13.6 trillion dollar economy and Russia’s GDP of just $1.7 trillion. Perhaps more significant is the argument from proponents of the Greater Eurasia idea that China can best be managed within a multilateral framework, and that a wider Greater Eurasian Partnership—which might include Russia, India, and China, along with the ASEAN countries—could reduce some of the potential frictions caused by China’s rapid rise in the Eurasian region. In this geopolitical geometry, China might be the economic leader, but not a hegemon, because within a loose Greater Eurasian partnership “Beijing will be balanced by Moscow, Delhi, Tokyo, Seoul, Teheran, Jakarta, and Manila."22 Russia might not be able to complete economically, but would play an indispensable role as the primary security actor across Eurasia, securing China’s transport routes and strategic flanks in Central Asia, the Middle East and the Arctic. Yefremenko argues that, within Greater Eurasia, Russia could play the role of “sheriff,” having proved itself so effectively in Syria.23 Such views are met with skepticism in China, which has its own growing security footprint across Eurasia.

The ideological aspects of the project may also cause concern in Beijing. For most of its advocates, an exact geography of Greater Eurasia is less important than ideational aspects. Space is important, writes Yefremenko, but Greater Eurasia is also an ideological alternative to the form of liberal globalization that stalled during the 2008 financial crisis.24 Yefremenko does not espouse a “formal military-political alliance against the U.S.,” but argues that “China and Russia will act in solidarity in the deconstruction of the American-centric world order and the construction of a more just and secure system of international relations in Eurasia and in the world."25 At a trilateral meeting of heads of state of India, Russia, and China in Osaka in June 2019, President Xi commented that the three states should promote “a more multipolar world and the democratization of international relations,26 shorthand for challenging what is viewed as a U.S. dominated international order.

Yet, despite this kind of rhetoric and growing tensions with the United States, China remains cautious about any radical revisionism. Foreign Minister Wang Yi recently stated, “We must observe and preserve the existing order. China cannot and will not start a new order."27 Economically, China has much more at stake in the current international order than does Russia, and is unlikely to welcome Russian strategic talk of an emerging bipolar order between a transatlantic bloc led by the United States and a loose configuration, led by Russia and China, in Greater Eurasia.28

The idea of Greater Eurasia as a Sino-Russian challenge to U.S. hegemony is also viewed as dangerously confrontational by more mainstream foreign policy thinkers in Moscow. Dmitry Trenin, Director of the Carnegie Center in Moscow, has argued, “Russia's mission is not to change the world order, or overthrow the U.S. from the position of leading global power.” Above all, Greater Eurasia should not be a platform to form “a kind of anti-American alliance with China.” Instead, Russia should maintain a balanced foreign policy, avoiding dependence either on China or on Europe. Such a policy, Trenin believes, will lead to a kind of “geopolitical loneliness” for Russia. This need not be wholly negative: without the entanglements of alliances and even alignments, Russia would be free to exercise its sovereignty and achieve a rare status in international politics—the capacity to be free.29

In a 2018 article, Kremlin ideologue Vladislav Surkov had also predicted “a hundred years (or possibly two hundred or three hundred) of geopolitical loneliness,” in which Russia, characterized by “double-headed statehood, hybrid mentality, intercontinental territory and bipolar history,” would be allied only with itself.30 Surkov argues that the shift to “geopolitical loneliness” marks a sharp break with Russia’s Eurocentric strategic orientation of the past 400 years. This “lonely” Russia would end its constant oscillation between East and West and its attempts to resolve Russia’s geopolitical dilemmas through new spatial projects.

This idea is also not new. Geopolitical isolationism also has an important place in Russian strategic culture: the apocryphal words of Alexander III, that “Russia has only two allies: its army and navy,” continue to have more resonance in Russian strategic thinking than such grand visions as Greater Eurasia. Yet this kind of self-isolation offers little to Russia in terms of meeting the challenges of a complex and interdependent world. To successfully balance its relations with China and other East Asian states and begin to resolve its difficult relations with the West, Russia needs more far-reaching strategic innovation that goes beyond the slogans of the “Eastern Pivot” and “Greater Eurasia.”

For Academic Citation

David Lewis, “Strategic Culture and Russia’s ‘Pivot to the East:’ Russia, China, and ‘Greater Eurasia,’ ” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 34, July 2019, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/strategic-culture-and-russias-pivot-east-russia-china-and-greater-eurasia-0.

Notes

1 For a discussion of Russia’s “Asianness,” see Milan Hauner, What is Asia to Us? Russia's Asian Heartland Yesterday and Today (Boston: Unwin & Hyman, 1990).

2 Paul J. Bolt and Sharyl N. Cross, China, Russia, and Twenty-first Century Global Geopolitics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

3 Peter Hopkirk, Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin's Dream of an Empire in Asia (London: John Murray, 1984).

4 Sergei Radchenko, Unwanted Visionaries: The Soviet Failure in Asia at the End of the Cold War, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

5 For more on the “pivot,” see Alexander Korolev, “Russia’s Reorientation to Asia: Causes and Strategic Implications,” Pacific Affairs 89, no. 1 (2016): 53–73; Gilbert Rozman, “The Russian Pivot to Asia,” The Asan Forum (November–December 2014), http://www.theasanforum.org/the-russian-pivot-to-asia; Fiona Hill and Bobo Lo, “Putin’s Pivot: Why Russia is Looking East,” Foreign Affairs, July 31, 2013, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139617/fiona-hill-and-bobo-lo/putins-pivot.

6 President of Russia, Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly, Moscow, December 12, 2013, http://eng.kremlin.ru/transcripts/6402.

7 Timofei Bordachev, “Novoye yevraziistvo: Kak sdelat’ sopryazhenie rabotayushchim,” Rossiya v global’noi politike, October 14, 2015, https://globalaffairs.ru/number/Novoe-evraziistvo-17754.

8 Viktor Larin, “Novaya geopolitika dlya vostochnoi Evrazii,” Rossiya v global’noi politike, September 13, 2018, accessed Juny 4, 2019, https://globalaffairs.ru/number/Novaya-geopolitika-dlya-Vostochnoi-Evrazii-1973.

9 Sergei Karaganov, “EAES: ot zemedleniya k uglubleniiu,” Rossiiskaia gazeta, December 4, 2018, https://rg.ru/2018/12/04/karaganov-integraciia-v-ramkah-eaes-prinosit-politicheskie-vygody.html.

10 The most comprehensive account of this relationship is Erica Downs, James Henderson, Mikkal E. Herberg, Shoichi Itoh, Meghan L. O’Sullivan, Morena Skalamera, and Can Soylu, The Emerging Russia-Asia Energy Nexus, National Bureau of Asian Research, December 2018, https://www.nbr.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/special_report_74_emerging_russia-asia_energy_nexus_dec2018.pdf.

11 Franz-Stefan Gady, “Russia Confirms Delivery of 10 Su-35 Fighter Jets to China by Year’s End,” The Diplomat, August 29, 2018; Franz-Stefan Gady, “China’s Military Accepts First S-400 Missile Air Defense Regiment From Russia,” The Diplomat, July 26, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/07/chinas-military-accepts-first-s-400-missile-air-defense-regiment-from-russia.

12 Alexander Gabuev, “Why Russia and China Are Strengthening Security Ties,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2018.

13 Michael J. Green, “Should America Fear a New Sino-Russian Alliance,” Foreign Policy, August 13, 2014; Mathieu Boulègue, “Russia's Vostok Exercises Were Both Serious Planning and a Show,” Chatham House, September 17, 2018.

14 Alexander Gabuev, “Russia Joins the AIIB ... Finally,” The Moscow Times, April 1, 2015, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2015/04/01/russia-joins-the-aiib-finally-a45354.

15 Charles Schlacks, Ilya Vinkovetsky, and Petr Savitskii, Exodus to the East: Forebodings and Events: An Affirmation of the Eurasians Exodus to the East (Idyllwild, Calif.: Charles Schlacks, 1996).

16 Marlene Laruelle, “When Eurasia looks east: is Eurasianism Sinophile or Sinophobe,” in M. Bassin and G. Pozo, eds, The Politics of Eurasianism: Identity, Popular Culture and Russia's Foreign Policy (London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017), 145–159.

17 Timofei Bordachev, “Main Results of 2017: Energetic Russia and the Greater Eurasia Community,” December 28, 2017, http://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/main-results-of-2017-energetic-russia. The original report was published in English as “Toward the Great Ocean-3: Creating Central Eurasia: The Silk Road Economic Belt and the priorities of the Eurasian states’ joint development,” Valdai Discussion Club, June 2015. For an overview, see David G. Lewis, “Geopolitical Imaginaries in Russian Foreign Policy: the Evolution of ‘Greater Eurasia,’” Europe-Asia Studies 70, no. 10 (November 2018): 1612–1637.

18 ‘Astana: Naryshkin: uspeshnaya rabota YEAES s KNR pomozhet sozdat’ Bol’shuiu Evraziyu,’ RIA Novosti, October 6, 2015, https://ria.ru/20151006/1297516870.html.

19 Vladimir Putin, “Plenarnoe zasedanie Peterburgskogo mezhdunarodnogo ekonomicheskogo foruma,” June 17, 2016, http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/52178.

20 “Putin: evraziiskoe partnerstvo dolzhno izmenit politicheskii landshaft kontinenta,” RIA Novosti, May 14, 2017, http://1prime.ru/News/20170514/827449765.html.

21 “Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation,” President of Russia, webpage, April 26, 2019, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/60378.

22 Sergei Karaganov, “God pobed. Shto dal’she?” Rossiya v global’noi politike, January 16, 2017.

23 Dmitri Yefremenko, “Rozhdenie Bol’shoi Evrazii,” Rossiya v global’noi politike, November 28, 2016.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Catherine Wong and Wendy Wu, “Xi Jinping says China, Russia and India should take ‘global responsibility’ to protect interests,” South China Morning Post, June 29, 2019,https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3016581/xi-jinping-says-china-russia-and-india-should-take-global.

27 Michael D. Swaine, “Chinese Views on the State of Sino-U.S. Relations in 2018,” December 1, 2018, https://www.prcleader.org/sinousrelations.

28 Fyodor Lukyanov, “Voina i mir XXI veka. Mezhdunarodnaya stabil’nost’ i balans novogo tipa,” Valdai Discussion Club report, Rossiya v global’noi politike, February 10, 2016, accessed date July 4, 2019, https://globalaffairs.ru/valday/Voina-i-mir---XXI-veka-Mezhdunarodnaya--stabilnost-i--balans--novogo-tipa-17971.

29 D. Trenin, “Konturnaya karta rossiiskoi geopolitiki: vozmozhnaya strategiya Moskvy v Bol’shoi Yevrazii,” Carnegie Center Moscow, February 11, 2019, accessed July 4, 2019, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/78913.

30 V. Surkov, “The Loneliness of the Half-Breed,” Russia in Global Affairs, May 28, 2018, https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/book/The-Loneliness-of-the-Half-Breed-19575.

About the Author

David Lewis is Associate Professor of International Relations, Department of Politics, at the University of Exeter. David’s research interests include international security and conflict studies as well as post-Soviet politics in Russia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. He is Co-PI for this project.

Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)

This program of research, led by the GCMC and funded by RSI (U.S. Department of Defense effort to enhance understanding of the Russian way of war in order to inform strategy and planning), employs in-depth case studies to better understand Russian strategic behavior in order to mitigate miscalculation in relations.

The Marshall Center Security Insights

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 13,985 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Security Insights series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.