Russia’s Security Council: Where Policy, Personality, and Process Meet

Executive Summary

- The Security Council, an autonomous element of the wider Russian Presidential Administration, is the central body responsible for managing the formulation and execution of security-related policies.

- It has a variety of roles both formal and informal, as well as considerable influence—not least because of the trust Russian President Vladimir Putin places in its veteran secretary, Nikolai Patrushev. However, it does not have direct authority over the security agencies and ministries, and it is often more a broker of consensus than anything else.

- As a structure, it can best be characterized as a conservative renovator: Its leadership is committed to preserving Russia’s existing strategic culture and operational code but also appreciates the need for technical reform to preserve the fundamentals.

The Russian Security Council (SB, for sovet bezopasnosti) was established in 1992 as a successor and counterpart to the Soviet Security Council. According to Article 1 of the Presidential Decree of May 6, 2011, “On the Security Council of the Russian Federation,” it is a constitutional deliberative body that prepares decisions of the President of the Russian Federation on issues of state security, public safety, environmental safety, personal safety, other types of security provided for by the legislation of the Russian Federation (hereinafter – national security), the organization of defense, military construction, defense production, military and military-technical cooperation of the Russian Federation with foreign states on other issues related to the protection of the constitutional order, the sovereignty of the Russian Federation, its independence and territorial integrity, as well as for international cooperation in the field of security.1

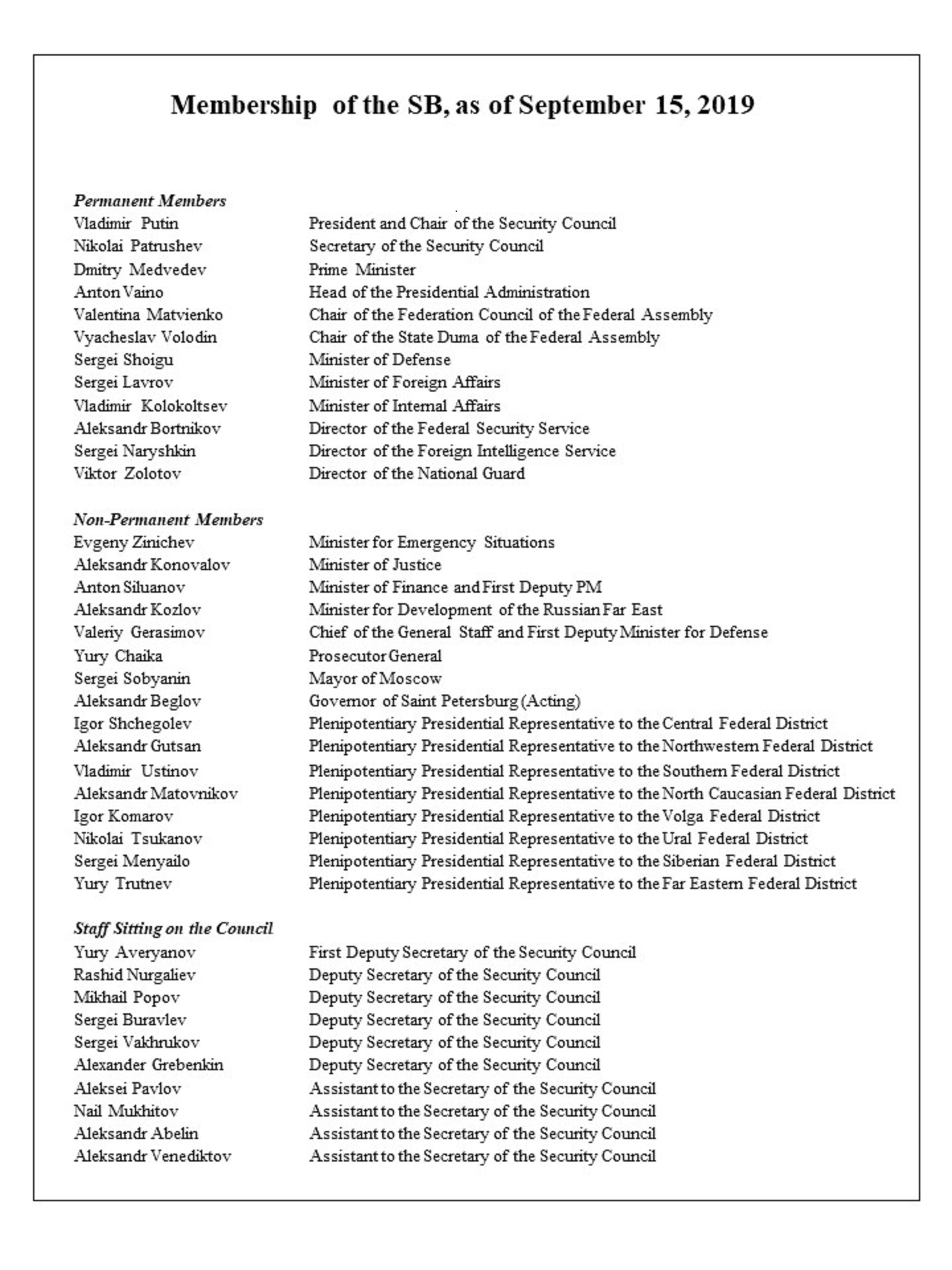

Formally a directorate of the Presidential Administration (AP: administratsiya prezidenta), in practice it is a functionally autonomous body whose secretariat works largely out of offices on Ipatevskii Alley, close to the main AP hub on Staraya Ploshchad in Moscow. It is chaired by the president and is composed of permanent members who are there ex officio, such as the ministers of defense and foreign affairs and others appointed by the president. The secretary—since 2008, this has been Nikolai Patrushev—is appointed by and reports directly to the president, but runs the day-to-day business of the SB and its secretariat. The secretary also manages a series of standing committees working on matters from ecological security to Commonwealth of Independent States affairs.

To some, the SB is essentially a revenant of the Soviet Communist Party’s ruling Politburo; to others, it is “once a very influential center of power, then a place of honorary retirement for time- served bureaucrats.”2 However, it appears that in spite of its considerable influence, its actual power is limited and largely vested in Patrushev himself.

In practice, the SB and its secretariat have five main functions:

- Develop high-level statements of government policy, such as the 2015 National Security Strategy. The role of the SB here is to both draft such policies and be a broker of various institutional stakeholder interests.

- Provide a place where key government figures can meet to discuss security policy on a formal level. However, as will be discussed later, this is less about shaping policy and more about addressing its execution and resolving any practical disputes that it may create.

- Informally, the SB is a place where siloviki (“men of force”—those in the military and security agencies) can meet, air their views and discuss issues of common interest. Beyond the formal sessions attended by ministers and agency heads, the regular routine of other meetings offers similar opportunities for their deputies and senior subordinates— arguably an even more important and useful function.

- Provide analytic support to the president and wider AP, especially as it relates to intelligence-related materials.

- The SB secretary is analogous to the U.S. national security adviser and provides regular briefings and advice. The secretary also frequently acts as a “security diplomat” for high- level talks in both Russia and abroad.

The SB is, in many ways, analogous to the part of the British Cabinet Office devoted to supporting the National Security Council and the Joint Intelligence Organization.

Is It More Than Patrushev?

Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Federation Council Speaker Valentina Matviyenko before the expanded meeting of the Security Council.

Because Patrushev has been secretary of the SB for over a decade (none of his predecessors lasted more than three years, and many only a matter of months),3 it is inevitable that perceptions of the role and power of the institution and its chief become blurred. Patrushev has considerable institutional power because of his position, but his authority also reflects his own personal characteristics and connections.

He is the former head of the Federal Security Service (FSB: federalnaya sluzhba bezopasnosti) and patron of his successor, Alexander Bortnikov. He also appears to have a productive relationship with Putin, who cited him as one of his trusted allies in his autobiography.4 He is not one of the president’s personal friends, though. He does not go hunting with him, like Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, or take to the judo mats or ice hockey rink with him, like the wealthy Rotenberg brothers or Gennadi Timchenko. Instead, much as with former AP head Sergei Ivanov, Patrushev’s relationship with Putin is based on loyalty, ideological proximity, a common background in the security services (specifically, the KGB), and, ultimately, the president’s trust.5

Patrushev certainly has his own hawkish agenda. He has repeatedly expressed the view that the West—by which he means essentially the United States—seeks to constrain or even dismantle Russia. He was one of the advocates for annexing the Crimean peninsula in 2014, and since then has embraced the new geopolitical confrontation.6 Well-connected liberal commentator Alexei Venediktov portrays him as a leading light of what Venediktov calls the “mobilization party” within the elite—one driven by a vision of a Russia that is statist, nationalist, and authoritarian, a faction that includes such figures as Rosneft head Igor Sechin and financier Yuri Kovalchuk.7 Indeed, Andrei Piontkovskii—who, to be sure, is no friend of the Kremlin—says Patrushev “sees himself under Putin in the Fourth World War as a military Chekist dictator.”8 In specific terms, he also appears to have been given informal lead responsibility over Balkans policy (including, as noted below, in the attempted coup in Montenegro in 2016).

Likewise, given the length of his tenure and his personal character—described by one former insider as “forceful, incisive, like Putin with a sharper sense of humor”9—it is inevitable that he has built an SB secretariat in his own image. He selects his own deputies and their assistants, with the possible exception of former Interior Minister Rashid Nurgaliev, who needed to be found a suitable new job when his previous position became untenable.

However, Patrushev’s capacity to shape the rest of the SB staff should not be overstated. The upper echelons of the Russian political system attract ambitious, opportunistic, and pragmatic individuals who are able to profess loyalty to their patron today and dispassionately change their allegiances tomorrow. Several former SB officials have gone on to higher positions and now espouse perspectives different from Patrushev’s. Federal Customs Service head Vladimir Bulavin was first deputy secretary of the SB from 2008 through 2013, and was rumored to have acquired his (lucrative) new position through his connection to Patrushev. However, he has since gravitated away from his erstwhile patron’s political faction and toward another old colleague, first deputy head of the Presidential Administration, Sergei Kirienko.

Culture and Clout

Whether the SB is essentially an extension of Patrushev’s will and worldview, or a body in which there is room for multiple perspectives (within relatively narrow bounds) and contending fiefdoms, there are four crucial questions about the organization, its identity, and its role within Russian policymaking.

1. Is the SB a Governing Body or an Administrative One?

The men (and one woman) on the SB represent key players within the Russian political system, and any institution in which those players all sit is, necessarily, a locus of power. However, is the SB powerful in its own right, or simply by virtue of its membership? And, by extension, is this a place where decisions are made, or simply promulgated and organized?

This is hard to prove one way or the other because of the opacity of the Russian system. However, there seems to be little evidence that formal SB sessions are seriously intended to reach important decisions: The sessions are large and the schedule is relatively full. When it is possible to identify points at which decisions are made, it generally involves smaller ad hoc groups. The decision to seize Crimea, for example, appears to have been made at a meeting of Putin, Patrushev, Bortnikov, and former AP head Sergei Ivanov, following a longer strategy session which included the other permanent SB members.10

Sessions of the full Security Council appear to be an opportunity to promulgate policy, to discuss the execution thereof (and especially to identify potential problems relating to interagency cooperation), and sometimes to resolve disputes.

2. Does the SB Command or Coordinate?

Is the SB an institution that manages operations, even if only at a strategic level? The evidence suggests that it does not: it delegates such functions to other bodies, or simply contributes to the formulation of tasking. In part, this is simply a product of size. The SB secretariat has expanded from the 200 staff it had in 2000, but not enough substantially to overflow its existing premises, and it has many day-to-day administrative and analytic duties.11 The SB’s capacity to drive policy is also constrained by a fundamental tension: Patrushev himself may be a “player,” but for the SB to perform its core function as a broker and coordinator within an often cannibalistic security apparatus, it needs to be quietly engaged in activities which would step on other agencies’ toes. Even Patrushev’s adventure in Montenegro was initiation by a nationalist minigarch and largely conducted by military intelligence.12

To this end, the SB’s role is more often to empower and monitor standing groups such as the National Counter-Terrorism Committee (which is headed by the FSB director, but reports to the SB) and ad hoc task forces (such as that which handled security for the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics). This, again, was headed by an FSB officer, Oleg Syromolotov—then the service’s deputy director and head of its Counter-Espionage Service (SKR)—but given both the importance of the event and the need for this to be a smoothly operating multiagency venture, the Sochi security group not only reported to the SB, but “curators” from Ipatevskii Alley apparently “were on call if needed to bring pressure to bear on any [agency] not playing its full part.”13

3. Is the SB a Political Actor or an Impresario?

The SB clearly has a wider political role. It influences legislation, its senior officials make public statements, it briefs politicians and journalists, and it sets the general government security agenda. Again, though, the question is this: how much it is a player in its own right, pushing its own agenda; and how much it is simply an arm of the Kremlin or the AP, managing others in the name of their agenda?

The SB certainly does appear to have a significant role in initiating, lobbying for, and even writing key legislation and policy decisions. This is especially evident where there is not an existing powerful institution already driving policy, suggesting that the SB is not anywhere near as dominant as some might suggest. Thus, the Defense Ministry and General Staff still have the loudest voice on military affairs, for example, and the FSB on counter-intelligence. However, information security is a good example of a policy area in which the SB has sway. The so-called “Yarovaya laws” ostensibly combatting terrorism through controls on technology and the internet—though named for their Parliamentary sponsor, Irina Yarovaya—are generally understood to be drafted by the SB.14 Likewise, in his recent decision to reserve key 5G frequencies for military use, Putin appears to have been following SB recommendations.15

4. Is the SB a Think Tank or a Secretariat?

Does the SB generate and develop its own ideas or it is really a clearinghouse for those of others? By extension, if it has any kind of role as a thought-leading institution, does it perform an essentially conservative role, policing individuals’ and organizations’ adherence to established strategic culture and operational code,16 or is it able to change that culture and code?

Patrushev is clearly a vocal and high-profile figure within Russian foreign and security politics, but there does appear to be, as noted previously, a distinction to be drawn between him and the Security Council secretariat and its administrative role. The latter clearly does more than simply collate and reconcile the views of other institutions, especially when it comes to drafting primary documents, but it is also heavily dependent on securing the assent of not just the president but also key stakeholders.

Therefore, the SB could probably best be characterized as a conservative renovator, whose leadership perceive it as being committed to preserving existing code and culture but, like any smart conservative, they appreciate the need for technical reform to preserve the fundamentals. A good example would be the 2016 Information Security Doctrine, which the SB played the main role in drafting: it applied existing approaches to this emerging area of contention.

Given its role as an imaginative, authoritative, and central coordinator and enforcer of ideas developed elsewhere, the SB is at once an actor and a theater. The fact is that Patrushev has not been able to use it to shape policy directly. He instead relies on his personal relationship to Putin, and his silovik allies, which emphasizes that his position is powerful at least as much because he is the one holding it as because of its integral authority. This, in many ways, is a metaphor for the SB itself.

For Academic Citation

Mark Garleotti, “Russia’s Security Council: Where Policy, Personality, and Process Meet,” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 41, October 2019,

https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/russias-security-council-where-policy-personality-and-process-meet-0.

Notes

1 Dmitri Medvedev, “On the Security Council of the Russian Federation,” May 6, 2011.

2 J. William Derleth, “The Evolution of the Russian Polity: The Case of the Security Council,” Communist and Post- Communist Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1, March 1996; Carolina Vendil, “The Russian Security Council,” European Security, No. 10, Vol. 2, Summer 2001; Leonid Volkov, “Isterika pensionerov,” Spektr, July 18, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(96)80011-0.

3 Yury Skokov (April 1992–May 1993), Evgeny Shaposhnikov (June 1993–September 1993), Oleg Lobov (September 1993–June 1996), Aleksandr Lebed (June 1996–October 1996), Ivan Rybkin (October 1996-March 1998), Andrei Kokoshin (March 1998– September 1998), Nikolai Bordyuzha (September 1998-March 1999), Vladimir Putin (March 1999–August 1999), Sergei Ivanov (November 1999–March 2001), Vladimir Rushailo (March 2001–March 2004), Igor Ivanov (March 2004–June 2007), Valentin Sobolev (acting) (June 2007–May 2008), Nikolai Patrushev (May 2008–present).

4 Vladimir Putin, First Person (New York: Hachette [PublicAffairs]), 2000, p. 201.

5 For an excellent take on the complexities of Putin’s relationship with Ivanov, see chapter 8 of Mikhail Zygar, All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin (New York: Hachette [PublicAffairs]), 2016.

6 Roget Kanet, ed. Routledge Handbook of Russian Security (Abingdon, UK: Routledge), 2019, pp. 127–128.

7 Alexey Venediktov, “Budem nablyudat’,” interview with Sergei Buntman, Ekho Moskvy, April 20, 2019, https://echo.msk.ru/programs/observation/2410945-echo/.

8 Andrei Piontkovskii, “Zhizn’ posle smerti. Andrei Piontkovskii—o Putine u vlasti,” Radio Svoboda, August 14, 2019, https://www.svoboda.org/a/30106033.html.

9 Conversation with the author, Moscow, 2013.

10 Steven Lee Myers, “Russia’s Move Into Ukraine Said to Be Born in Shadows,” New York Times, March 8, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/08/world/europe/russias-move-into-ukraine-said-to-be-born-in-shadows.html; BBC News, “Putin Reveals Secrets of Russia's Crimea Takeover Plot,” March 9, 2015, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-31796226.

11 This is discussed further in Mark Galeotti, Controlling Chaos: How Russia Manages Its Political War in Europe, ECFR Policy Brief, September 1, 2017, https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/controlling chaos how russia manages its political war in europe.

12 Howard Amos, “Vladimir Putin’s Man in the Balkans,” Politico, June 21, 2017, https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-balkans-point-man-nikolai-patrushev/; Mark Galeotti, Do the Western Balkans Face a Coming Russian Storm? ECFR Policy Brief, April 4, 2018, https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/do_the_western_balkans_face_a_coming_russian_storm.

13 Conversation with MVD officer involved in the operation, Moscow, 2015. See also Mark Galeotti, “Modern Counter-Terrorism in Sochi: More Like Counter-Espionage,” In Moscow’s Shadows, webpage, February 14, 2014, https://inmoscowsshadows.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/modern-counter-terrorism-in-sochi-more-like-counter- espionage/.

14 Maria Kolomychenko and Polina Nikolskaya, “Russia’s Telecoms Security Push Hits Snag—It Needs Foreign Help,” Reuters, July 5, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN1JV12Y; “’Nu, kak v internete posideli:’ pol’zovateli prokommentirovali podpisanie zakonov Yarovoi’,” Moskovskii komsomolets, June 7, 2016, https://www.mk.ru/politics/2016/07/07/nu-kak-v-internete-posideli-polzovateli-prokommentirovali-podpisanie-zakonov-yarovoy.html.

15 “Putin ne otdaet operatoram populyarnye chastoty dlya 5G,” Vedomosti, August 15, 2019, https://www.vedomosti.ru/technology/articles/2019/08/14/808820-putin-ne-otdaet.

16 Strategic culture is essentially a nation’s fundamental set of assumptions about what constitutes a threat and how and when force is appropriate to resist it, while operational code is a more granular and often more rapidly evolving notion of how best to operate in conflicts.

About the Author

Mark Galeotti is an Honorary Professor at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies and a Senior Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, as well as a Senior Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute of International Relations Prague and previously head of its Centre for European Security. Now based in London, for the academic year 2018-19 he is a Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute. He is an expert and prolific author on transnational crime and Russian security affairs.

Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)

This program of research, led by the GCMC and funded by RSI (U.S. Department of Defense effort to enhance understanding of the Russian way of war in order to inform strategy and planning), employs in-depth case studies to better understand Russian strategic behavior in order to mitigate miscalculation in relations.

The Marshall Center Security Insights

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 13,985 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Security Insights series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.