An Emerging Strategic Partnership: Trends in Russia-China Military Cooperation

Executive Summary

- Since 2014, Russia and China have developed a strategic partnership, primarily due to enhanced military cooperation, including sales of advanced military equipment and an increasingly robust program of bilateral and multi-lateral military exercises. Economic and diplomatic cooperation have also increased, though to a much lesser extent.

- Bilateral cooperation is unlikely to advance to the level of a full alliance because of differences in geopolitical interests and asymmetries of power, with Russia remaining reluctant to fully acknowledge China’s geopolitical rise.

- Actions by the United States to pressure both Russia and China have the effect of pushing the two countries closer together. To prevent a closer partnership, the United States should focus on creating areas of policy divergence between the two states.

Introduction

There is widespread consensus among scholars that, although Russia and China have been moving toward closer cooperation through the entire post-Soviet era, the trend has accelerated rapidly since 2014.1 The relationship was boosted by Russian leaders’ belief that Russia could survive its sudden confrontation with the West only by finding an alternative external partner. China was the obvious candidate because it had a suitably large economy, was not openly hostile to Russia, and was not planning to impose sanctions in response to the Ukraine crisis.

Since 2014, the bilateral relationship has been focused on increased military cooperation, closer economic ties, and an increase in coordination on responses to various issues in international politics. Although some advances have occurred in all three areas, military cooperation has advanced the most. As discussed in more detail later in this paper, Russia and China have institutionalized a comprehensive mechanism for military consultation, expanded military technical cooperation initiatives and military personnel exchanges, and expanded regular joint military exercises. In the diplomatic sphere, Russia and China have supported each other in various international organizations and worked to establish new international institutions that could act as alternatives to existing Western-dominated institutions.2

Although economic cooperation is the weakest aspect of the Russia-China alignment, it has progressed a great deal, particularly in the energy field. “China is eager to increase energy relations with Russian companies,… [while] Russian concern over its increased dependence on China in the East is deemed secondary to expanding Russia’s customer base beyond the still dominant European market.”3 At the same time, there have been limits to this cooperation, particularly in the economic and financial sectors outside of the energy sphere. China refused to help Russia overcome the effects of Western economic sanctions and bilateral trade and trade in national currencies has remained limited, with little diversification of trade and investments. On the political side, neither country has shown itself to be prepared to support the other’s geopolitical interests if doing so would hurt its own interests.4

This policy brief focuses primarily on strategic and military cooperation, where the two sides have made the greatest progress. After briefly discussing the prospects for a strategic partnership between Russia and China, I examine the progress in and remaining constraints on expanding bilateral military cooperation, outline three scenarios for future cooperation in this sphere, and conclude with a discussion of how the United States should respond.

Strategic Partnership?

As bilateral cooperation has progressed, analysts have increasingly examined whether the Russia-China relationship has reached a level of strategic partnership. The growing consensus is that it has.5 According to Alexander Korolev, the partnership is neither ad hoc nor temporary and provides clear benefits for both sides:

Through this partnership, Russia can gain access to more instruments for promoting its agenda of balancing the United States and enhancing its version of multi-polarity in Europe. China, in turn, receives Russia’s political backing and access to Russia’s energy resources and military technologies, which are essential assets for China in its growing tensions with the U.S. in Asia.6

Some Russian scholars are even more optimistic about the trajectory of the relationship, suggesting that, over time, the two states might even develop an alliance.7

At the same time, there is a similar consensus forming that the current upward trend in Russia-China strategic cooperation should not be viewed as irreversible. In particular, scholars note that, should Russia’s challenge to the United States start to destabilize the international system, it may also jeopardize China’s peaceful rise. This would lead to a divergence in the countries’ interests and potentially cause a rift between the two powers to emerge.8 Some scholars argue that the geopolitical and economic factors that have hindered Russia’s past Asian pivots could have a similar effect again, although this is distinctly a minority position. One possibility proposed by analysts who hold this view is that a future leadership transition in Russia might result in a policy shift back toward a preference for closer relations with Europe, undermining the long-term prospects of Russia’s partnership with China.9

Central Asia represents one potential area of tension between Russia and China, because the two states have formulated competing regional influence projects for the region. As a result, some analysts believe that the two countries may be heading toward a strategic rivalry caused by China’s increasing desire to play a role in Central Asian security and by competition over energy export routes and trade connectivity in general.10 A more likely scenario, however, is that the two countries will maintain a division of responsibilities that allows them to continue to cooperate in the region, with Russia taking primary responsibility for security issues while China focuses on economic development.11

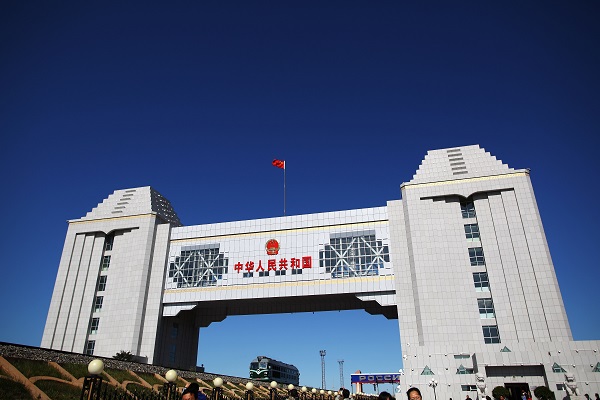

The global coronavirus pandemic initially introduced another source of tension into the Russia-China relationship, especially since Russia moved quickly in late January to close its borders with China. This move was seen by some observers as an indicator of a lack of trust in Chinese information, since China at the time was still making an effort to minimize the scope and threat of the epidemic. At the same time, the almost immediate decision to reopen the border to commercial traffic highlighted Russia’s dependence on Chinese goods.12 As it turned out, even this partial closure proved to be economically damaging, especially in the Russian Far East.13 However, any residual tension was overcome once China largely ended community spread of the virus. Once the threat of spread was over, the two countries developed complementary information campaigns designed to highlight their mutual assistance in the crisis and the superiority of authoritarian systems over democratic ones in marshalling resources to fight the pandemic.14

Future of Bilateral Military Cooperation

Russian senior officials have highlighted the special nature of Russia’s defense relationship with China by characterizing the ties in terms of a strategic partnership. As the two countries have expanded the number of military exercises and consultations while deepening military technical cooperation, analysts have suggested a growing alignment between the two countries at a political level that allows for stronger defense ties. This does not mean that Russia and China are about to enter a military alliance. As cogently argued by Michael Kofman, Russian and Chinese leaders have labeled the relationship a strategic alliance because a military alliance is not needed, given that the two countries do not need each other for security guarantees or extended nuclear deterrence. That said, they have sought to make their ties more formal, as shown by the 2017 agreement on a three-year road map to establish a legal framework to govern military cooperation. This framework is expected to be completed and signed later in 2020, further codifying various aspects of defense ties, including the option of conducting joint long-range aviation patrols.15

Military Technical Cooperation

Although China was Russia’s leading client for military hardware in the 1990s and early 2000s, the arms sales relationship sharply declined after 2006 because of a combination of Chinese unhappiness with Russian pricing policies and the poor maintenance record of Russian equipment, as well as Russian concerns about China’s tendency to reverse-engineer Russian equipment for both its own use and export abroad. Russian arms sales to China saw a modest revival post-2011 but expanded most substantially after the Ukraine crisis, with agreements for the sale of S-400 air defense systems and Su-35 combat aircraft signaling the end of Russia’s informal ban on sales of advanced weapon systems to China.16 In October 2019, Vladimir Putin announced that Russia was helping China develop its own ballistic missile early warning system. Russia’s new willingness to share information related to strategic nuclear weapons highlights the extent to which old sensitivities about sharing advanced military technology with China has dissipated in recent years.17 Russia has also turned to China for electronic components and naval diesel engines that it could no longer obtain from the West. Most significantly, military cooperation and defense ties improved as defense sales declined, making clear that such ties are driven at the senior political level and not tied to arms sales.

However, Russia faces a difficult choice this decade in either providing advanced technology to China, knowing that the technology will most likely be copied, or forgoing arms sales but with the expectation that China’s defense sector will develop comparable systems in the near future. The previous Russian arms export strategy of selling the “second-best” technology available while staying a generation ahead is no longer viable. China’s defense industry has sufficiently caught up with or worked around Russia via defense-cooperation deals with other countries that it is now only interested in the most-advanced Russian weapons available. China’s advances in weapon design and general goal of self-sufficiency in military production suggest that Russian arms sales will never reach the peak achieved in the early 2000s and that China will emerge as a stronger arms market competitor to Russia over time.

Military Exercises

Military exercises are a central pillar of bilateral military relations. Moscow and Beijing have recently been rapidly expanding the scale and pace of their joint exercise activity far beyond the two traditional programs, the Peace Mission ground forces exercises in Central Asia and the Joint Sea naval exercises. Both of the long-standing exercise programs have had an anti-U.S. character, with gradually increasing levels of complexity and joint activity. However, the exercises have been criticized for being overly scripted and poorly coordinated, as well as for continuing to lack a joint command structure.18 These criticisms are not necessarily warranted, as the purposes of the exercises are primarily to build military ties at the senior level and to signal political intentions rather than to establish interoperability. There has been no evidence that Russia and China intend to operate in a joint command structure; such a structure would not make sense for two countries that have not entered a formal military alliance.

The naval exercises between Russia and China have been more effective in terms of providing realistic operational experience, although they have not focused particularly on interoperability between the two navies. Naval exercises are not only becoming more frequent but also are being held in new geographical areas. Before the Ukraine crisis, Russia refused to hold bilateral exercises in such controversial territories as southern China near Taiwan. Since 2015, however, naval exercises have been held in areas such as the Baltic and South China Seas as a way of signaling the two countries’ growing power, expanding military ties, and mutual displeasure with the United States.19 Recent trilateral exercises with Iran represent another example of this steady expansion in the use of exercises for political signaling, now including third nations.20 Given China’s desire to be more visible in the European maritime theater, one can expect an increase in exercises that serve the Chinese desire to show its flag in distant waters.

Since 2015, the two countries have expanded their repertoire of exercises, including adding joint missile defense exercises in response to the U.S. deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in South Korea. Most observers are aware of growing Chinese participation in Russian strategic exercises, including Vostok-2018 and Tsentr-2019. A joint

Russian-Chinese bomber patrol in July 2019 demonstrated that Moscow is increasingly willing to disregard the interests of other states in the Asia-Pacific region in its pursuit of a closer military relationship with China.21

These exercises are primarily focused on setting a positive tone for military-to-military ties at the highest levels, rather than increasing interoperability at the tactical level. The exercises suggest that Russian-Chinese military cooperation in the air domain, which lags naval exercises, will increase. Stronger participation of Chinese air assets in Tsentr-2019 further substantiates this observed trend.22 Space is the next likely frontier for expanding cooperation, although it may be limited given sensitivities about the technologies involved in this domain.

Limitations on Bilateral Military Cooperation

Despite steady progress over the past decade, there remain significant geopolitical and technical constraints on military cooperation between Russia and China. Although senior Chinese and Russian officials repeatedly and publicly affirm that their relationship is characterized by great trust, in reality, a lack of mutual trust remains an obstacle to more robust cooperation. Although Russia and China formally settled the last of their border disputes in 2008, there are still regions where the two sides’ geopolitical interests may not align in the long term. Russia remains concerned over potential Chinese encroachment into the Russian Far East. Russia’s concerns are fueled by a combination of past Chinese claims to territory Russia annexed in the 1800s and the contrast between the sparsely populated Russian Far East and the densely populated Chinese border regions, which have generated ongoing Chinese immigration. A military incursion is seen as unlikely by Moscow relative to the more insidious problem of what Russian leaders fear could prove to be (1) a creeping annexation, in which China projects influence into parts of the Russian Far East on a de facto basis through a large influx of illegal Chinese immigrants, and (2) a steady reorientation of the Russian Far East toward more economically attractive Chinese markets and away from the distant center of power in Moscow.

As the relative balance of influence in Central Asia continues to shift more in favor of China, the potential for the two sides to clash over interests in the region remains significant. Beijing has steadily supplanted Russia as the principal economic power in Central Asia in terms of investment and lending. Still, countries in the region continue to look primarily to Russia to defend their security interests; additionally, Russia remains the principal labor market for this region.

Thus far, this de facto division of labor has enabled Russia and China to maintain a reasonably stable working relationship in Central Asia, such that they do not step on each other’s vital national interests or security concerns. However, as China’s Belt and Road Initiative develops, its economic footprint in Central Asia is likely to grow larger, which could lead to tensions between Beijing and Moscow.

Russia has sought to play a key role in the development of the Arctic region; in particular, it plans to capitalize on new energy sources, as well as the opening of the Northern Sea Route. While Moscow has been willing to work with other members of the Arctic Council, Russia has been reluctant to allow non-Arctic powers, such as China, to play a major role in the region. By contrast, a resource-hungry China has plans to extend its presence to the Arctic and is building its first domestically-produced icebreaker. Although none of these geopolitical concerns are currently likely to cause tensions that could limit military cooperation between Russia and China, they could be factors in the long term.

The asymmetry in economic power between the two countries, including their potential regional influence and global heft, has grown more visible. Furthermore, Russian strategic culture, long having seen itself as superior to China, is visibly struggling with the new realities of this power balance. As a result, Russian political elites have yet to come to terms with China’s rise. Finally, both countries are deeply nationalistic and prestige-seeking, which means neither would be particularly willing to subordinate its military to the leadership of the other. Russian leaders’ desire to maintain an independent foreign policy means that they will not accept Chinese leadership or impose limitations on their relationships with other countries for the sake of Chinese foreign policy. Although the two countries seek to manage conflict over core interests, most international competition is seen as fair game, whether it is arms sales or foreign direct investment.

Russia and China have placed a low priority on achieving greater interoperability during joint military exercises, reflecting an enduring lack of interest on the part of both sides in developing the kind of integrated military capability needed to conduct effective joint military operations.23 At the tactical level, issues such as language and communication highlight that these are decidedly different military structures, with different planning processes and organizational cultures. This limits what the Chinese are able to learn from their counterparts.

China is seen as a predatory power by many Russian experts, so there is a natural degree of apprehension among the Russian military. General Staffs plan contingencies around capabilities, because intent can change. This is especially so when dealing with another great power that is self-admittedly revisionist in its ambitions. Despite the positive outlook of Russia’s national leadership on the benefits of a growing Sino-Russian alignment, the military establishment will always see the Chinese military as a potential adversary and plan accordingly.

Scenarios for Future Russia-China Military Cooperation

The impact of various scenarios for the development of Russia-China military cooperation on U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific region is inversely correlated with their likelihood. That is, the most likely scenarios are relatively low impact, while the highest-impact scenarios are very unlikely to develop. In this section, I outline three scenarios for future military cooperation between Russia and China.

Low Impact, High Probability

In a low-impact, high-probability scenario, Russia and China expand their military cooperation by holding additional joint naval exercises with countries that are seen as adversarial to the United States and expanding the visibility of their maritime presence both in the Pacific and the Mediterranean regions. As noted earlier, previous joint naval exercises have been conducted in the South China Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Baltic Sea, and future theaters could include other areas within the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Expanded exercises in these regions would serve the two countries’ respective purposes, as Russia seeks greater visibility in the Asia-Pacific and China seeks greater visibility in the European maritime theater.

Both countries seek to reciprocate U.S. freedom-of-navigation operations to the extent possible by visiting the Western Hemisphere. Russia and China could agree to hold a naval exercise in the Caribbean Sea, hosted by Venezuela or Cuba. Such an exercise would have little long-term impact on either Russia’s or China’s geopolitical influence in Latin America and it would not do much to improve their military capabilities or naval interoperability. It would, however, generate a great deal of media attention, highlighting the countries’ ostensible global reach and potential strategic partnership. In other words, both countries could feel that they had scored a propaganda win at relatively low cost, but the actual impact on regional security would be negligible.

Medium Impact, Medium Probability

A medium-impact, medium-probability scenario might focus on additional sales of Russian advanced military equipment. The most interesting systems for China would include diesel-electric submarines, over-the-horizon radar systems, early warning systems, space-related technology for satellites, microchips, and next-generation aircraft engines. In return, Russia might accelerate the purchase of Chinese defense-industrial components, such as heavy-lift cranes, machine tools, and circuitry board components and parts. Although Russia would benefit substantially from procuring Chinese surface combatant vessels, given the shortcomings in those parts of the Russian defense-industrial complex, the financial interests of Russia’s domestic defense industry would likely prevent such deals from being made.

The two countries could also build on Russia’s recent sale to China of S-400 long-range air defense systems to agree to the sale of Russian S-500 air defense systems once those come online. S-500 systems would have a longer range than existing systems owned by China and may have the capability of defending against a wider range of missile types. These capabilities would lead to a significant improvement in Chinese air defense capabilities versus the United States and its allies. China would seek to acquire the 40N6 extended-range (400-km) missile, which has reached initial operating capability with the S-400, either as part of an S-500 deal or on its own for China’s existing S-400 systems.

High Impact, Low Probability

A number of highly unlikely but potentially very damaging scenarios present themselves. One such area would involve greater Russian-Chinese defense industrial cooperation on sensitive technology, such as theater hypersonic weapons or submarine quieting. Although military establishments on both sides would almost certainly resist allowing the other side access to such technology, if such cooperation did develop, it would substantially affect the ability of the United States to maintain a favorable regional military balance and retain a technological edge in certain domains over China. One possibility for enhanced defense cooperation that has been discussed in recent years, though with little progress to date, is a potential technology transfer deal in which Moscow would provide Beijing with the RD-180 rocket engine in exchange for space-grade microelectronic components.24 Past discussion centered on trading finished equipment, but a closer relationship between Russia and China may result in consideration of exchanging production technology in the future. Such a deal would increase China’s lift capacity and Russia’s ability to produce advanced guidance and control systems.

Another scenario in this category is a joint military intervention, most likely in a Central Asian country in the event of a political crisis or instability, because Russia and China have previously conducted exercises to deconflict areas of responsibility in this type of scenario. However, one should not exclude the possibility of a joint Russian-Chinese intervention in Africa or the Middle East. While the countries lack core interests in these regions, the cost and risk of intervention is also dramatically lower and the barrier for entry in such operations is not especially high. Both countries have the expeditionary capacity to conduct relatively small force deployments around much of the world and might well seek to do so together in response to a contingency where their interests align.

The least likely, but nonetheless possible, scenario is a military crisis with the United States in which one country takes advantage of a situation to press for geopolitical gains. For example, in the event of a standoff between the United States and China, Russia would seek to leverage the distraction of the United States to make opportunistic gains. Russia could deploy forces to Asia or provide military assistance via deniable means to China in order to raise costs to the United States. Because China is quite remote from Europe, the likelihood of Chinese involvement in a crisis between Russia and members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe is too low to be worth considering.

How Should the United States Respond?

There is a general perception among experts that greater cooperation between Russia and China is inevitable, given the core precepts of present-day U.S. foreign policy. Scholars focused on relative power suggest that the two countries will inevitably balance against the most powerful country in the international system.25 Furthermore, U.S. efforts to pursue a hard line against either Russia or China, and especially against both at the same time, have the effect of driving the two countries closer together. For some scholars, this suggests that accommodating them within the existing international order would be a more effective response.26 Scholars focused on the role played by ideas highlight the perceived threat of liberal ideology and suggest that if the United States reduces its emphasis on democracy promotion and regime change, this would reduce the impetus to Russian-Chinese cooperation.27

In this geopolitical environment, actions by the United States that threaten Russia and China in a similar manner or present a common security challenge will have the effect of driving the two countries closer together. This is especially true if the actions are strategic in nature. Examples of such actions include the deployment of missile defense systems or freedom-of-navigation operations near the shores of either Russia or China. Both of these actions create a perception among Russian and Chinese leaders that they share a common global security challenge from the United States—and one that is serious enough that they would be best served by facing it together.

On the other hand, actions that disaggregate the nature of the threat perceived by Russian and Chinese leaders would help create divergence in their interests and thereby slow the trend toward a closer bilateral relationship. For example, the United States could challenge Russia in ways that are exclusive to the European theater, such as by pulsing additional troops to NATO member states for exercises. Similarly, China could be challenged in the regions of Taiwan and Southeast Asia rather than in East Asia or maritime territories adjacent to Russian territory. Russian relations with such countries as Vietnam and India could be exploited to highlight potential tensions between Russia and China.

For Academic Citation

Dmitry Gorenburg, “An Emerging Strategic Partnership: Trends in Russia-China Military Cooperation,” Marshall Center Security Insight, no.54 (April 2020):

https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/emerging-strategic-partnership-trends-russia-china-military-cooperation-0.

Notes

1 Alexander Gabuev, Friends with Benefits? Russian-Chinese Relations After the Ukraine Crisis, Carnegie Moscow Center, June 29 2016, https://carnegie.ru/2016/06/29/friends-with-benefits-russian-chinese-relations-after-ukraine-crisis-pub-63953.

2 Alexander Korolev, “How Closely Aligned Are China and Russia? Measuring Strategic Cooperation in IR,” International Politics, May 2019.

3 Tom Røseth, “Russia’s Energy Relations with China: Passing the Strategic Threshold?” Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2017, pp. 23–55.

4 Mikhail Korostikov, Дружба на расстоянии руки: Как Москва и Пекин определили границы допустимого [“Friendship at Arms’ Length: How Moscow and Beijing Determined the Boundaries of the Permissible”], Kommersant, May 31, 2019, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3984186.

5 Tom Røseth, “Moscow’s Response to a Rising China: Russia’s Partnership Policies in Its Military Relations with Beijing,” Problems of Post-Communism, Vol. 66, No. 4, 2019, pp. 268–286.

6 Korolev, 2019, p. 29.

7 Vassily Kashin, “Is the Conflict Inevitable? Not at All. How Reasonable Are Western Expectations of a Russia-China Confrontation?” Russia in Global Affairs, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2017

8 Andrej Krickovic, “The Symbiotic China-Russia Partnership: Cautious Riser and Desperate Challenger,” Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2017, pp. 299–329.

9 Chris Miller, “Will Russia’s Pivot to Asia Last?” Orbis, Winter 2020. See also Mikhail Karpov, “The Grandeur and Miseries of Russia’s ‘Turn to the East’: Russian-Chinese ‘Strategic Partnership’ in the Wake of the Ukraine Crisis and Western Sanctions,” Russia in Global Affairs, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2018.

10 Carla P. Freeman, “New Strategies for an Old Rivalry? China–Russia Relations in Central Asia After the Energy Boom,” Pacific Review, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2018, pp. 635–654.

11 Liselotte Odgaard, “Beijing’s Quest for Stability in Its Neighborhood: China’s Relations with Russia in Central Asia,” Asian Security, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2017, pp. 41–58.

12 Jake Rudnitsky and Evgenia Pismennaya, “Russia Closes Border With China to People, Not Goods,” Bloomberg News, January 30, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-30/russia-closing-border-with-china-to-affect-people-not-goods.

13 Andrew Higgins, “Businesses Getting Killed on Russian Border as Coronavirus Fears Rise,” New York Times, February 24, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/24/world/europe/coronavirus-russia-china-commerce.html.

14 Van Ivej, “Выход из Кризиса и Преимущества Китая, [Exit from Crisis and China’s Advantages],” Russia in Global Affairs, April 1, 2020, https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/vyhod-iz-krizisa-i-preimushhestva-kitaya/; Fyodor Lukyanov, “Вирус Разнообразия [Virus of Diversity],” Russia in Global Affairs, March 25, 2020, https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/virus-raznoobraziya/.

15 Michael Kofman, “Towards a Sino-Russian Entente?” Riddle, November 29, 2019, https://www.ridl.io/en/towards-a-sino-russian-entente.

16 Siemon Wezeman, “China, Russia and the Shifting Landscape of Arms Sales,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, July 5, 2017, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2017/china-russia-and-shifting-landscape-arms-sales.

17 Dmitry Stefanovich, “Russia to Help China Develop an Early Warning System,” The Diplomat, October 25, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/10/russia-to-help-china-develop-an-early-warning-system.

18 Daniel Urchik, “What We Learned from Peace Mission 2018,” Small Wars Journalundated, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/what-we-learned-peace-mission-2018.

19 Chris Buckley, “Russia to Join China in Naval Exercise in Disputed South China Sea,” New York Times, July 29, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/29/world/asia/russia-china-south-china-sea-naval-exercise.html and Andrew Higgins, “China and Russia Hold First Joint Naval Drill in the Baltic Sea,” New York Times, July 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/world/europe/china-russia-baltic-navy-exercises.html.

20 Andrew Osborn, “Russia, China, Iran Start Joint Naval Drills in Indian Ocean,” Reuters, December 27, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-military-russia-china/russia-china-iran-start-joint-naval-drills-in-indian-ocean-idUSKBN1YV0IB.

21 Franz-Stefan Gady, “The Significance of the First Ever China-Russia Strategic Bomber Patrol,” The Diplomat, July 25, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/the-significance-of-the-first-ever-china-russia-strategic-bomber-patrol/.

22 “China to Send 1,600 Troops, About 30 Aircraft to Russia’s Strategic Military Drills,” TASS, August 29, 2019, https://tass.com/defense/1075535.

23 Paul Schwartz, “The Military Dimension in Sino-Russian Relations,” in Jo Inge Bekkevold and Bobo Lo, eds. Sino-Russian Relations in the 21st Century, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), p. 105.

24 Eric Berger, “Russia Now Looking to Sell Its Prized Rocket Engines to China,” Ars Technica, January 18, 2018, https://arstechnica.com/science/2018/01/russia-now-looking-to-sell-its-prized-rocket-engines-to-china.

25 Robert S. Ross, “Sino‑Russian Relations: The False Promise of Russian Balancing,” International Politics, September 2019.

26 Krickovic, 2017.

27 John M. Owen IV, “Sino‑Russian Cooperation Against Liberal Hegemony,” International Politics, January 2020.

About the Author

Dr. Dmitry Gorenburg is a Senior Research Scientist at CNA, where he writes on security issues in the former Soviet Union, Russian military reform, Russian foreign policy, and ethnic politics and identity. His recent research topics include decision-making processes in the senior Russian leadership, Russian naval strategy in the Pacific and the Black Sea, and Russian maritime defense doctrine. In addition to his role at CNA, he currently serves as editor of Problems of Post-Communism and is an Associate of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University.

Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)

This program of research, led by the GCMC and funded by RSI (U.S. Department of Defense effort to enhance understanding of the Russian way of war in order to inform strategy and planning), employs in-depth case studies to better understand Russian strategic behavior in order to mitigate miscalculation in relations.

The Marshall Center Security Insights

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 14,000 professionals from 156 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Security Insights series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.