Economic Security in the Eastern Partnership

Security Challenges in the Eastern Partnership

The Eastern Partnership (EaP) is a joint initiative involving the European Union and Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. This region, located in a key strategic position between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, is a pivotal corridor at the crossroads of geopolitics and commerce, particularly oil and gas. Since the end of the Cold War and the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the region has undergone fundamental changes in terms of its economic and political development. The security debate over traditional and non-traditional factors in the region is very wide and broad in its scope and has had an impact on progress in regional cooperation, economic development, and good governance.

The geopolitical security context of the EaP region is very complex. The creation of these independent states has introduced a new vitality to the region, although these states must also contend with the issues arising from its location in a contested neighborhood dominated by protracted conflicts. The very term “protracted conflict” refers to conflicts in the West and Southwest of the former Soviet Union, involving separate conflicts that are all in different evolutionary phases. Abkhazia and South Ossetia involve the territory of Georgia, while the frozen conflict in Transnistria involves Moldova. Ukraine has been involved in conflicts since 2014 with the annexation of Crimea from Russia, while the conflict in the Donetsk-Luhansk area in southeastern Ukraine is in an intense phase. Nagorno-Karabakh, between Armenia and Azerbaijan, is another conflict that threatens to ignite again at any time.

These conflicts make the neighborhood “contested” and regional cooperation very difficult. Three main dimensions add to the traditional complexity of Europe’s Eastern Flank.

Geographically, it relates to the major transport and trade arteries of the Black Sea; from the energy security perspective, it involves the changing nature of the threats and the actors that want to maintain control over natural resources; and politically it concerns the future of this region between the East and the West.

The common player in this picture is Russia, which is trying to keep the region under its economic and political influence, creating dependencies and preventing the countries from exercising free choices when it comes to Euro-Atlantic aspirations. On the other hand, the vague road to European Union (EU) membership for the states in the region provides Russia the opportunity to make influential counter-offers. Populist trends in the region also often result in divided populations and political establishments over the future of their countries.

The EaP countries have gone through a multidimensional and difficult transition process on the economic, political, diplomatic, and institutional fronts. Despite the diversity among the countries, internal challenges affect the region as a whole, such as democratization and reforms, economic development, energy security, and Euro-Atlantic integration.

Economic Security

Economic security is among the main challenges facing the countries in the EaP region. The notion of economic security is a complex one, generally describing the ability of a countryeptto protect and advance its economic interests in the face of events, developments, or actions that might block these interests. It considers the identification and management of weaknesses, vulnerabilities, risks, and threats to economic stability and it involves strategic decision-making on how to use vital resources. Economic security in this region is strongly related to good governance and control of corruption. High levels of corruption throughout the region extract an enormous economic price, while its hidden social costs are even higher.

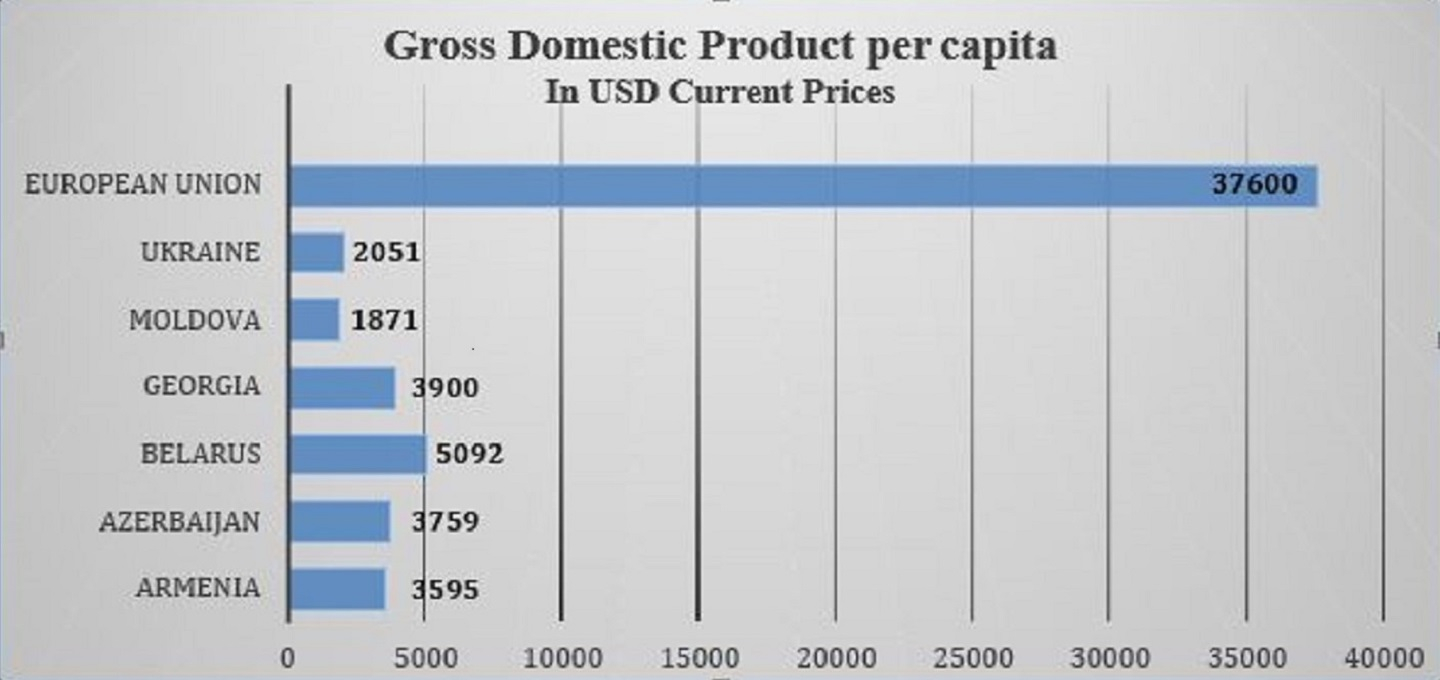

Enduring poverty, high unemployment rates, and deep levels of inequality threaten the everyday security of average citizens in the region. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the average per capita income in the region in 2016 was only $3,378 per year, which is only eight percent of the European Union’s average income per capita. Figure 1 illustrates this disparity.

Moldova is the poorest country in the region with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita of only $1,871 in 2016. Countries that have the highest income per capita are the richest in natural resources, but there is not much economic modernization or transformation in these countries. (Figure 11)

Despite some encouraging positive growth trends in the region over the last two decades, economic development remains below satisfactory levels. Indirectly affected by the world economic recession in 2009 through trade and finance spillover channels, the economic downturn has worsened socio-economic conditions throughout the region, threatening the initial optimism of eventual convergence with advanced Western European countries. While the regional economy is in a recovery, this recovery remains slow, with sluggish economic growth rates.

The dire economic situation has deepened inequalities, socially dividing societies in terms of income and wealth levels, as well as declining living standards, thereby shaking the foundations of these societies. Energy security is another challenge that hinders economic development in the region. On one side, wealth in natural resources presents many opportunities to transfer Caspian oil and gas to the European markets, raising hopes for regional economic development and cooperation. On the other side, competition over control of pipelines, shipping lanes, and transport routes in order to secure increased political and economic influence raises the risks of regional disagreements. The EaP economies are heavily dependent on Russian gas and oil, with Russia using this “superpower” for political leverage and to foster dependency rather than economic development and growth.

The modernization and advancement of infrastructure is a precondition for energy diversification and substantial economic growth. Two elements are crucial in this case. First, financial support and investment is needed for specific projects and to develop energy infrastructure. Second, time is of paramount importance for the success of these projects. While European companies are slow in constructing alternative pipelines from the Caspian basin, Russia has indicated a willingness to launch new pipeline projects that could make some Western initiatives obsolete.

Catching up with the West

The transition economic model in the EaP region has been an extractive one, mainly led by imports and domestic demand expansion, driven by natural resources and the artificial accumulation of physical and financial capital. Agriculture remains a significant sector of the regional economy, making the economy dependent on rural development. The large-scale privatization process of state-owned enterprises has not been effective, generally favoring market monopolies and fueling widespread corruption. In the absence of an efficient industrial capacity and the limited role of innovation in the economy, as well as a lack of real structural reforms, all the countries in the region have large shadow economies, high sovereign debts, and a serious lack of competitiveness.

While the greatest aspiration of all the countries in the region is sustainable economic development, achieving this goal will prove highly challenging due to the global economic crisis, persisting regional rivalries and domestic structural weaknesses. What is imperative for improving the standards of living of the population is greater transparency, improved governance, and real implementation of reforms.

In the first phase of economic transition, from 1990 until 1995, the Black Sea countries went through a period of sharp economic decline, witnessing the collapse of the old systems of industrial production and distribution; weak or non-existent legal frameworks; dysfunctional financial sectors; inconsistent structural reforms; and macroeconomic instability. The second phase, between 1995 and 1999, saw a certain stabilization and consolidation of regional economies with improved security and political stability, strengthening of the first generation of market-oriented structural reforms, and some signs of macroeconomic stability.

The third phase, from 2000 to the end 2008, was a period of high economic growth rates, with real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increases for the region averaging more than 8.5% per year. The high growth rates translated into higher living standards, increased trade and investment, and the integration of the region into the broader global economic context.

The fourth phase, starting in 2009, was marked by a sharp halt in growth rates as a consequence of the negative spillover effects of the global economic crisis. This subjected the financial and banking system to extreme stress. Government interventions throughout the region averted a crash of the financial system, but the crisis highlighted the weaknesses and vulnerabilities of the system. The regional economy contracted on average at -6% in 2009, with the exception of Azerbaijan. Today, while the economic recession is in the past, recovery is very slow, with sluggish and unsustainable economic growth rates. (Figure 22)

Weak Rule of Law and High Levels of Corruption Hinder Economic Development

The main economic challenges are similar for all the countries in the EaP area; they include barriers to market access such as weakness in the rule of law; high levels of corruption; excessive bureaucracy; and ineffective judicial systems. All these factors limit the ability of local entrepreneurs and foreign investors to do business in the region. Weak rule of law is the most significant restriction on economic development, affecting all the other factors. Despite the fact that governments have expanded their efforts to advance and modernize the legislation, at least on paper, implementation of these laws has been very weak, exposing the limited capacity and will of both the judiciary and the administration to apply the new laws.

Corruption is widespread in the region, with most countries experiencing a deterioration of corruption’s perception levels during the last decade. Georgia is the outstanding exception in this picture, having been successful in its implementation of anti-corruption reforms in the period between 2003-2013. This resulted in a large relative reduction in corruption (mainly petty), thereby improving Georgia’s Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index ranking from 130th place in 2005 to the 44th in 2016.

While corruption is a global concern that adversely affects everyone, it takes a much heavier toll in poorer countries. Corruption in the EaP countries, as in other transition countries, is mainly a rule of law and governance issue that feeds economic underdevelopment. A highly corrupt country runs the risk of being trapped in a vicious downward spiral, leading to the institutionalization of corruption. Weak governance, corruption, and poverty create a vicious cycle that destroys opportunities and development. Rules and regulations are circumvented by bribes, public management is undermined by illicit money, and free media is silenced through political control. High levels of corruption in public administration and the judiciary remain a primary concern for businesses seeking a fair and predictable economic climate. (Figure 33)

Economic, political, and geographical factors on Europe’s eastern flank have affected high levels of corruption. The economic transition period from centralized to market economy has created massive opportunities for the appropriation of rents, resulting in enormous illicit gains for individuals in a short time.

Despite the fact that democracy levels and pro-European Union rhetoric have advanced in the region, it seems that this has not helped with the anti-corruption reforms. One of the key EU priorities for economic and societal development in the region has been strengthening institutions and good governance, with a special focus on the fight against corruption. Unfortunately, although the political elite in the region has paid lip service to European integration, they have not seriously addressed the corruption that is deeply ingrained in its political and economic systems. Over the past two decades, democratic competition and free media have helped Eastern European countries to reduce corruption through internal corrective mechanisms of democracy.

Sadly, what has worked in this region does not seem to have yielded the same results in the Eastern Partnership countries. The risk is that when pro-European politicians fail to deliver in their good governance reforms, disappointment with the ruling parties can quickly translate into disenchantment with the EU, as well. The trends in this region are very concerning. In Moldova, public support for European integration stood at around 74 percent in 2009, but it has recently declined to less than 40 percent.

Foreign Direct Investment

The EaP region has opened up to international investors and markets during the last two decades. In addition to a relatively cheap and relatively educated labor force, the wealth in natural resources, the area is attractive to investors as a good launching point for new markets. Despite its strategic location, the region as a whole has attracted less than 0.49 percent of the world’s total stock of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). (Figure 44)

Current FDI in this region is related to natural resources and the privatization process, however there is a lack of greenfield investments. Although the demand for FDI is enormous, there is a deadlock because FDI is needed for the development of infrastructure, but—because of poor infrastructure—investors are reluctant to invest. Foreign investors are also discouraged because of disputes over property rights; administrative barriers; non-transparent privatization processes; weak results in fighting corruption; and the thriving informal market. The region suffers a serious lack of absorptive capacities for attracting and reaping the full benefits of the FDI; these challenges are a result of factors such as deficiencies in the fair and efficient rule of law; lack of human capital; weak financial sectors; and insufficient economic openness. Moldova, the poorest country in the EaP region, attracts the least FDI, with only $35 per capita in inflows of FDI in 2016 and a total stock of $882 per capita. It is followed by Ukraine, with only $75 per capita in inflows of FDI in 2016 and stock of 1084.

International investors are crucial for continued economic growth in the region. Good governance reforms pay off when it comes to their impact on economic development. Georgia is the perfect example. The drastic anti-corruption reforms that started in 2003 not only dramatically improved its position in the Transparency International ranking, but also in the World Bank’s Ease Doing Business rankings, moving from the 112th position in 2004 to the 16th in 2016. Serious economic and good governance reforms designed to liberalize the market, increase transparency, and improve efficiency enhanced Georgia’s ability to attract large inflows of FDI. Foreign direct investment in Georgia increased more than six-fold, rising from a stock of

$423 per capita in 2004 to $3545 in 2016, according to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). At the same time, the GDP per capita increased three- fold in a little more than ten years, from $1,135 in 2004 to $3900 per capita in 2016. Other examples in the neighborhood are the new member states of the EU, Bulgaria and Romania, which both almost doubled the inflow of FDI into their countries immediately after NATO and EU accession.

Economic Integration Dilemma

One of the most important successes for three of the Eastern Partnership countries, namely Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, has been the signing of Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA) with the EU, which improved economic relations between these countries and the EU. While the DCFTAs have enormously increased trade between the EU and the three countries, they have also become a very important instrument of trade liberalization and institutional harmonization, increasing the competitiveness of domestic companies in the region.

At the same time, however, the economic integration dilemma between the EU common market and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) remains a deep divisive issue. Armenia and Belarus are part of the Eurasian Economic Union, together with Russia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. There are essential disparities between the EU and the EEU, such as the purpose of the organizations; their current economic state; the levels of corruption; and the complexity of the relationships.

The choice of the Eastern Partnership countries is not confined to the economy, but it is a choice of values. For all the EaP countries, with the exception of Belarus, the EU is the main trade partner and the main investor; Belarus is the only country in the region that trades more with Russia than with the EU.

The EEU, formally created in 2013, mimics the EU in its format, in the sense that its declared purpose is free trade and economic integration, but in reality its proclaimed customs union is not even a free-trade area, since only import tariffs have been harmonized, but not export tariffs. The EEU $4 trillion market represents less than 2 percent of global GDP at the current exchange rate, compared to the EU, which represents the largest and the most advanced market in the world, with more than 17 percent of global GDP. Members of the EEU vary greatly in terms of economic development and structure; econometric calculations suggest that the EEU causes more trade diversion than trade generation, reducing the common value added. With the exception of Russia, the other member states even complain that they have lost their economic competitiveness since they joined EEU.

While there is easier access to the EEU, the political agenda dominates the economic one. Russia views and uses the EEU politically as an “iron curtain” against the EU’s influence in the region. This is the reason why there is a “geo-politicization” of the issue in the Eastern Partnership countries. In countries such as Moldova, there is an increase of public support for the EEU, with over forty percent of the population wanting to join it; this is larger than the support for the EU. The EU is the main trade partner for Moldova with more than sixty percent of its exports going to EU countries and only about ten percent of the exports going to Russia, but the EEU is becoming interesting because of political issues, creating a polarization of the society. The main argument used by its political supporters is the labor mobility of young Moldovans, who can do seasonal work in Russia, which offers about 500,000 opportunities for employment, compared to 300,000 positions in the EU countries. It is also surprising that public support for EEU is increasing in Georgia, the most pro Euro-Atlantic country in the region, with latest data showing that about 30 percent of the population is looking at EEU as an economic alternative.

The main difference between the EU and the EEU is the predictability of the partners. Russia is an unpredictable partner, whose market is based on extractive industries and not on innovation and know-how. EU integration might be distant for the EaP countries, but the process of integration is very important for strengthening the institutions and modernizing the economies of the aspirant countries. This has been proven in the eleven Eastern European countries that have already joined the EU, which benefited greatly from adopting EU rules and standards for modernizing their economies.

The Way Ahead

Building economic resilience is imperative and requires a multidimensional and regional approach.

- It is crucial to strengthen the rule of law in the EaP countries. To foster economic development, it is imperative to create a friendly business environment through simplification of procedures, judiciary reforms, and an effective fight against corruption. Effective rule of law is necessary to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which is crucial for sustainable development in the region. For economic growth to be sustainable and to translate into increased wellbeing for the population, it has to be inclusive, based on competitive development of the private sector, focused on qualitative education, and investments in the basic and digital infrastructure. Good and transparent governance are key to promoting the development of resilient, democratic societies that able to realize their potential.

- The European Union integration process is the most important driver for serous economic and political reforms in the region. Membership in the EU may seem distant, but the EU instruments for support in structural reforms, infrastructure projects, and good governance are crucial. The EU is supporting inclusive economic and social development of the region through people-to-people mobility and through the visa free regime with the three countries, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, but also through the active support for civil society. The EU has made a significant financial commitment to the region in support of the agreed reforms in the partner countries, with more than EUR 3.3 billion, since the launch of EaP. Moldova is the recipient of the highest amount of EU aid per capita worldwide, while Ukraine has been the largest recipient of EU aid during the transition process.

- Regional economic cooperation through the promotion of free trade agreements or regional infrastructural projects is imperative to boost the regional economy. A basic challenge in the EaP region is promoting regional cooperation. Traditional challenges and “protracted conflicts” have created the tendency for the states to exert more national control and fail to commit their resources for initiatives that involve risks, trusting others, or pool sovereignty. The downturn is thus an obstacle for new common regional initiatives, although there are certain instances where incentives to cooperate may increase, such as with initiatives that enhance economic security. These may involve reducing a country’s isolation or vulnerability or sharing information and pooling resources in a way that provides insurance against shocks, speculative attacks, and other destabilizing economic events. Even small bilateral or regional projects are extremely important for building relations. The EU is one of the main players that could foster this type of regional cooperation.

A successful transformation of the EaP region depends on both political and economic progress. Political and structural reforms without economic transformation can weaken public trust in democracy and fuel social and ethnic tensions, which could further undermine development and stability. The EU’s role is very important in building state and societal resilience in the EaP though economic and social development, conflict mitigation, tailored assistance, and conditionality to foster good governance.

For Academic Citation

Valbona Zeneli, “Economic Security in the Eastern Partnership,” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 21, September 2017, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/economic-security-eastern-partnership-0.

Notes

1 World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database April 2017, International Monetary Fund (IMF) as of 2 April 2017.

2 World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database April 2017, International Monetary Fund (IMF), as of 2 April 2017.

3 Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index, http://www.transparency.org/research/cpi/overview, as of 3 April 2017.

4 United Nations Conference on Trade and Developemnt (UNCTAD), UNCTAD STAT, Foreign Direct Investment, http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx, as of 10 September 2017.

About the Author

Dr. Valbona Zeneli is a professor of national security studies at the Marshall Center. Professor Zeneli’s current teaching and research interest include international economy, Southeast European security issues, institutional reforms, and good governance.

The Marshall Center Security Insights

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 13,715 professionals from 155 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Security Insights series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.