Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations

Executive Summary

- Active measures—covert political operations ranging from disinformation campaigns to staging insurrections—have a long and inglorious tradition in Russia and reflect a permanent wartime mentality, something dating back to the Soviet era and even tsarist Russia.

- A strategic culture whose participants see the world full of secret threats and an operational culture whose adherents regard the best defense as offense have ensured that both have become central aspects of modern Russia’s geopolitical struggle with the West.

- Active measures are not solely the preserve of the intelligence services, but of other actors as well, and these actors are expected to generate their own initiatives aimed at furthering the Kremlin’s disruptive agenda.

Aktivnye meropriyatiya, “active measures,” was a term used by the Soviet Union (USSR) from the 1950s onward to describe a gamut of covert and deniable political influence and subversion operations, including (but not limited to) the establishment of front organizations, the backing of friendly political movements, the orchestration of domestic unrest and the spread of disinformation. (Indeed, the Committee for State Security [KGB]’s Service A, its primary active measures department, was originally Service D, meaning disinformation.)

In many ways, active measures reflect the wartime mentality of the Soviet leadership, as similar tactics were used by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during the Second World War, but much less frequently thereafter. For the KGB, however, active measures increasingly became central to its mission abroad in the postwar period, something made explicit by then–KGB chair Yuri Andropov in his Directive No. 0066 of 19821 Tellingly, the KGB’s official definition of “intelligence” was “a secret form of political struggle which makes use of clandestine means and methods for acquiring secret information of interest and for carrying out active measures to exert influence on the adversary and weaken his political, economic, scientific and technical and military positions.”2

Such practices became less common during Gorbachev’s reform era and then in the chaotic 1990s, in part because of a desire to improve relations with the West and in part due to the collapse of Soviet and then Russian covert networks abroad. However, under President Vladimir Putin, Russia’s foreign intelligence services were restored to their old levels of funding and activity, and early hopes of a modus vivendi with the West soon foundered, hampered by unrealistic expectations and mutual suspicions. By the mid-2000s, active measures were no longer confined to the immediate neighborhood of the post-Soviet “Near Abroad” countries, but were again being seen as a central component of Moscow’s wider strategy. This change reflected a broad shift in strategic perspective best encapsulated by Alexander Vladimirov, a retired major-general who then chaired the military experts’ panel at the Russian International Affairs Council, an influential think tank close to the Russian Presidential Administration (AP). In 2007, he wrote that “modern wars are waged on the level of consciousness and ideas” and that “modern humanity exists in a state of permanent war” in which it is “eternally oscillating between phases of actual armed struggle and constant preparation for it."3

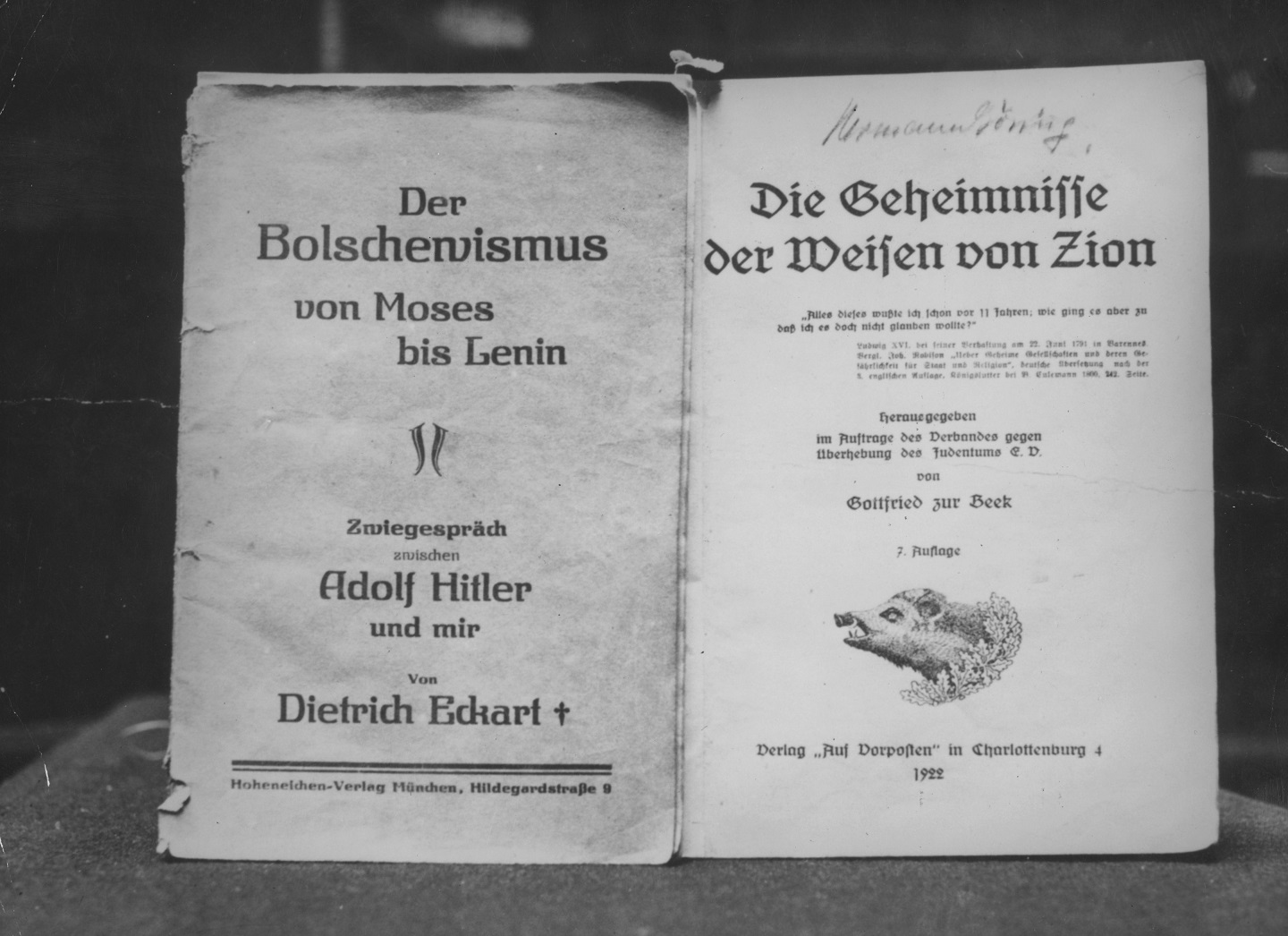

circa 1935: The title pages of 'The Protocols of the Elders of Zion', a Nazi anti-Semitic text.

Strategic Culture: A World of Covert Challenges

This perspective owes much to a strategic culture heavily predicated on the belief that the world is a demonstrably hostile place full of covert attempts to undermine Russia’s power institutions and roll back its international influence, and which is driven by rival interests, ideological divisions, and outright “Russophobia.” This culture has deep historical roots.

- Tsarist “conspirology:” More than in most European societies, tsarist domestic politics and geopolitical calculations were rooted in conspiracy theory and active myth-making. From the popularization of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (a secret police forgery that appeared to prove a Jewish plot to dominate the world) to the belief that Masonic cabals were orchestrating attacks on Russia from Europe in the nineteenth century, these conspiracies provided a constant backdrop to more conventional geopolitical calculations.4

- Soviet counter-revolutionary theory: Communist Party leadership, from the very beginning of the USSR, worked under the (not always inaccurate) assumption that the West was actively seeking to subvert not just the Soviet state, but later its Warsaw Pact subalterns, allies, and proxies elsewhere in the world. As a KGB officer of the time put it, the West was engaging in “subversive activity in the political and ideological sphere against the socialist countries,” while the Red Army’s Officer’s Handbook warned of a “vast system of anti-Communist propaganda… now aimed at weakening the unity of the socialist countries… and undermining socialist society from within.”5 Indeed, in 1979, then–Chairman of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, warned that “various anti-social phenomena or the negative activities of an insignificant handful of people” did not in themselves represent a threat individually, but that they posed a danger collectively as they were instruments of “ideological sabotage."6

- Russian color revolution theory: Like the Soviets, today’s Russian government sees an inevitable and inextricable link between external and domestic security. Since Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution through the other color revolutions and the Arab Spring of the 2010s, there has been a growing school of thought within Russian security circles that the West—essentially the United States—has been mastering “political technologies” able to topple governments through a mix of social media subversion and old-fashioned spycraft and economic pressure. Western encouragement of democratization, support for civil society and transparency, and efforts to encourage activists addressing issues such as corruption and human rights abuses are now seen as forms of such subversion. A crucial turning point was in the 2011–2012 Bolotnaya square protests, which at their peak saw perhaps 100,000 people on the streets of Moscow and in other major cities. President Barack Obama’s administration’s clear preference for then–President Dmitri Medvedev over Putin; its support for the protests; and its decision in late 2011 to appoint an outspoken champion of democratization, Michael McFaul, as the new U.S. Ambassador to Moscow were regarded by the Kremlin as proof that the protests were managed by the West. Putin personally accused then–U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton of sending “a signal” to “some actors in the country” to begin causing trouble “with the support of the U.S. State Department."7

Operational Code: Subverting the Subverters

For more than two centuries, the strategic worldview of Russian decision-makers has assumed that the country faces a constant and covert threat of subversion from outside, and that discontent at home is generated, magnified, and directed by foes abroad. As well as having serious implications for domestic politics, this worldview also creates a sense not only that subversion is a perfectly suitable instrument to use against Russia’s rivals, but that the boundaries between war and peace have become blurred to the point of being meaningless.

Under Putin, the Kremlin—and especially the civilian national security community of the AP and Security Council (SB) secretariats, as well as the intelligence community—has thus embraced a sense that Russia faces a Western campaign of subversion and that using active measures are the best and most logical response. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)’s Article 5 guarantee of mutual defense and the formidable risks in a direct challenge to a richer and, in overall terms, more powerful West would seem to preclude any military options. However, active measures make use of Russian strengths, not least the scale of its intelligence networks, to exploit perceived Western weaknesses—from its divisions to its commitment to free speech and open politics.

Of course, active measures have not replaced other methods and instruments, from conventional diplomacy to military force. For example, Chief of the General Staff, Valery Gerasimov, has had to adapt his rhetoric to include the threat of “hybrid war”—gibridnaya voina—as a Western tactic able to use “political, economic, informational, humanitarian, and other non-military measures” to shatter societies before direct military intervention.8 This quote came from his speech to the Academy of Military Sciences, summarized in a now-infamous article in the Voenno-promyshlennyi kur’er (Military-Industrial Courier) that launched many opinion pieces about a “new way of war.” However, it is unclear how far he was expressing a strongly-held view, and how far he was simply genuflecting to the concerns of the political leadership. The Russian military is, like other militaries around the world, exploring how non-kinetic means, from electronic warfare to psychological operations, can prepare the battlefield and supplement its direct combat operations. However, the focus of its planning, training, procurement, and thinking is still on conventional high-tempo offensive war.

Institutional Interests

It is thus worth noting the specific institutional interests at stake in Russian active measures, and the differing perspectives they have on their use and scope:

- The Foreign Ministry: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID) is a relatively conventional diplomatic service that has absorbed many of the values and methods of its overseas counterparts. Its diplomats thus often affect a degree of disdain for active measures, which they view as breaking the tacit codes of their trade, and they are concerned about the potential consequences of such measures. However, MID is a fairly weak actor in the Russian system and is often required to provide cover and support for other agencies. More to the point, it is still informed by Russia’s strategic culture and operational code. It has shown itself to be very eager to support and initiate (dis)information operations—more often disinformation—which are on the active measures spectrum. Some examples include the MID’s involvement in Germany’s infamous “Lisa Case,” which sought to stir up anti-immigrant populism,9 its outspoken efforts to confuse the narrative after the Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 shootdown in Ukraine in 2014, and its actions following the poisoning of defected former Russian military intelligence officer Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom in 2018.

- The media: The state-controlled and -dominated media clearly play a crucial role in disinformation operations, but it also supports and covers for other operations, including magnifying the impact of such operations. When, for example, a politically embarrassing telephone conversation10 between U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Victorian Nuland and U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt was intercepted by the Russian intelligence community, the extensive play in Russian foreign-language media outlets really gave this operation weight. While there is a degree of direct management of media operations from the AP, notably in weekly meetings between editors and presidential spokesman Dmitri Peskov, many activities are instead generated by television presenters, journalists, and editors. Without questioning the patriotic sentiments of many involved, to a considerable extent, engagement in such activities is driven by hopes of career advancement and the need to keep the authorities happy.

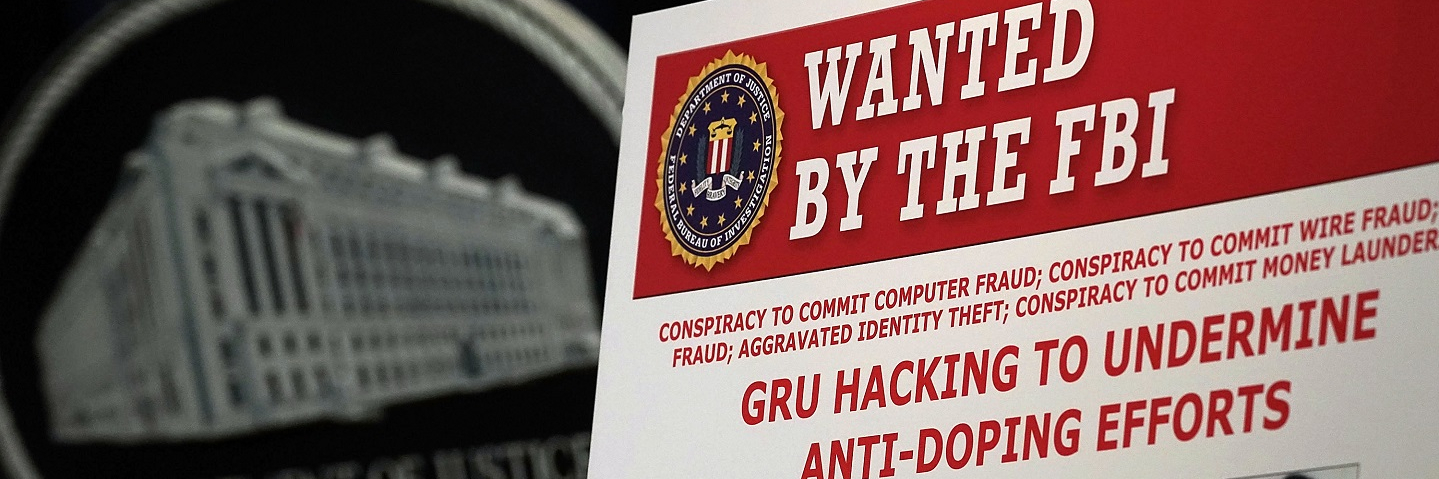

- The intelligence community: The intelligence agencies are at once the main players in Russian active measures and also the main beneficiaries of the Kremlin’s dependence on such methods. The Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Federal Security Service (FSB) and military intelligence (GRU) are all involved in a wide spectrum of operations. The GRU, for example, has been implicated in the hacking of U.S. political actors’ email accounts, as well as in an attempted coup in Montenegro and in the Skripal case.11 The SVR tried to stop attempts by Canadian unions to block a partnership between Bombardier and Russian aircraft manufacturers and to disrupt a name-change referendum in what is now known as North Macedonia.12 The FSB, while primarily a domestic security agency, is increasingly active abroad, and is linked with operations from the murder of Chechens in Turkey to recruiting criminals as intelligence assets in Estonia.13

- Presidential Administration: The AP (which includes the SB) is the nerve center of Putin’s deinstitutionalized state, and is the coordination center for those active measures which require interagency collaboration.14 Many of the AP’s departments are also directly involved with their own operations, from the Foreign Politics Department seeking to suborn foreign politicians and movements to the Presidential Council for Cossack Affairs encouraging paramilitary groups abroad. Active measures, as a reflection of a style of Russian foreign policy that enthusiastically ignores the constraints of traditional institutional roles and international etiquette, very much play to the country’s culture and perceived role. In effect, the more fluid and covert the policy, the more power and freedom of maneuver it gives the AP.

- The “Ad-hocrats:” However, in today’s deinstitutionalized Russia, it is also important to appreciate the extent to which all kinds of actors and agencies are using active measures to compete and demonstrate their value to the Kremlin, just as Andropov’s Directive No.0066 made active measures the responsibility of all the KGB, not just Service A.15 Everyone—from business people to clergymen, students to scholars—can generate their own initiatives that would often be considered covert acts of subversion and disruption.

Implications

Active measures are both an expression of Russia’s strategic culture, with its propensity to see the world as full of covert challenges, and the operational code of the Putin regime, which considers the best defense against such threats to be good offense. A central element of this code is that responsibility for active measures has become diversified, even universalized, linked with the way Russia has become an "adhocracy" of competing, semi-autonomous actors expected to generate their own plans to work toward the state’s broad objectives.

Of course, this does not mean that every Russian individual or institution is necessarily involved in active measures. Most are not, and furthermore, most of the initiatives generated should not be considered active measures, as they are often overt and well within the usual norms of political activity. However, the crowning irony is that it has become very easy for foreigners to see the Kremlin’s hand behind every reversal, every trip, and every Russian initiative. This has an undeniably baleful impact on international relations, but at the same time likely suits Putin well, crediting him with more influence and impact in the world than he and his Russia truly deserve. Perhaps this is the greatest active measure of all.

For Academic Citation

Mark Galeotti, “Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations,” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 31, June 2019, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/active-measures-russias-covert-geopolitical-operations-0.

Notes

1 Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West (Penguin, 2000): 316.

2 Quoted in Ivo Jurvee, The Resurrection of ‘Active Measures’: Intelligence Services as a Part of Russia’s Influencing Toolbox, Hybrid CoE Strategic Analysis (April 2018), https://www.hybridcoe.fi/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Strategic-Analysis-2018-4-Juurvee.pdf.

3 Alexander Vladimirov, Kontseptualnye osnovy natsionalnoi strategii Rossii: Voyennopoliticheskii aspekt (Nauka, 2007): 105, 130.

4 See, for example, Léon Poliakov, “The Topic of the Jewish Conspiracy in Russia (1905–1920), and the International Consequences,” in eds. Carl F. Graumann and Serge Moscovici, Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy (Springer, 1987); Marouf Hasian, “Understanding the Power of Conspiratorial Rhetoric: A Case study of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” Communication Studies 48, no. 3 (1997).

5 Andrew and Mitrokhin (2000), p. 324; S. N. Kazlov (ed.), The Officer’s Handbook: A Soviet View, Translated by the U.S. Air Force (Soviet Defence Ministry, 1971): 32.

6 Andrew and Mitrokhin (2000), 431.

7 David M. Herszenhorn and Ellen Barry, “Putin Contends Clinton Incited Unrest Over Vote,” New York Times, December 8, 2011.

8 Valery Gerasimov, “Tsennost’ nauki v predvidenii,” Voenno-promyshlennyi kur’er, February 26, 2013.

9 Stefan Meister, “The “Lisa Case”: Germany as a Target of Russian Disinformation,” NATO Review (2016), https://www.nato.int/docu/review/2016/Also-in-2016/lisa-case-germany-target-russian-disinformation/EN/index.htm.

10 “Ukraine crisis: Transcript of leaked Nuland-Pyatt call,” BBC News, February 7, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26079957.

11 U.S. Department of Justice, “U.S. Charges Russian GRU Officers with International Hacking and Related Influence and Disinformation Operations,” October 4, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-russian-gru-officers-international-hacking-and-related-influence-and; “Montenegrin Court Convicts All 14 Defendants Of Plotting Pro-Russia Coup,” RFE/RL, May 9, 2019, https://www.rferl.org/a/montenegro-court-convicts-14-on-terrorism-charges-/29930212.html; and UK Prime Minister’s Office, “PM Statement on the Salisbury Investigation: 5 September 2018,” September 5, 2018, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-the-salisbury-investigation-5-september-2018.

12 U.S. Department of Justice, “Evgeny Buryakov Pleads Guilty In Manhattan Federal Court In Connection With Conspiracy To Work For Russian Intelligence,” March 11, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/evgeny-buryakov-pleads-guilty-manhattan-federal-court-connection-conspiracy-work; Patrick Wintour, “Greece to Expel Russian Diplomats over Alleged Macedonia Interference,” Guardian, July 11, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/11/greece-to-expel-russian-diplomats-over-alleged-macedonia-interference.

13 “Have Russian Hitmen been Killing with Impunity in Turkey?” BBC News, December 13, 2016, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-38294204; Holder Roonemaa, “How Smuggler Helped Russia to Catch Estonian Officer,” re:Baltica, September 13, 2017, https://en.rebaltica.lv/2017/09/how-smuggler-helped-russia-to-catch-estonian-officer.

14 For more on the AP’s role, see Mark Galeotti, “Controlling Chaos: How Russia Manages its Political War in Europe,” ECFR Briefing, September 1, 2017, https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/controlling_chaos_how_russia_manages_its_political_war_in_europe.

15 For more on the concept of Russia as an “adhocracy,” see Business New Europe, 18 January 2017, https://www.intellinews.com/stolypin-russia-has-no-grand-plans-but-lots-of-adhocrats-114014.

For Academic Citation: Mark Galeotti, “Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations,” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 31, June 2019, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/active-measures-russias-covert-geopolitical-operations-0.

About the Author

Dr. Mark Galeotti is an Honorary Professor at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies and a Senior Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, as well as a Senior Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute of International Relations Prague and previously head of its Center for European Security. Now based in London, for the academic year 2018-19 he is a Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute. He is an expert and prolific author on transnational crime and Russian security affairs.

Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)

This program of research, led by the GCMC and funded by RSI (U.S. Department of Defense effort to enhance understanding of the Russian way of war in order to inform strategy and planning), employs in-depth case studies to better understand Russian strategic behavior in order to mitigate miscalculation in relations.

The Marshall Center Security Insights

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 13,985 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Security Insights series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.