Winter Has Come!

Introduction

This year our Strategic Competition Seminar Series (FY23 SCSS) activities focus on the theme of alternative Ukrainian future trajectories and the implications these may have for Russia and the West. Much has been assumed about the impact of winter on Russia’s ability to advance its invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine’s ability to resist, Western unity, and on increased pressure for a ceasefire – but on whose terms? This roundtable examines these interlinked themes.

Winter War?

In general terms, Russia expects winter will break western solidarity and resolve, increase calls for ceasefire on Russian terms, and undercut Ukraine’s morale and will to fight. Russian strikes against Ukraine’s energy grid have reduced in numbers, but are sustainable through the winter and have a cumulative effect. An operational pause appears underway, akin to August 2022 before Ukraine’s lightning counter attack in September to retake Kharkiv region, as each side probes the other in search of weakness, vulnerabilities, and opportunities. Ukraine makes small advances on the Svatove-Kremina line, for example, and undertakes long-range strikes against Russian supply nodes, while Russia makes slow incremental gains around Bakhmut.

When surveying Russian mainstream commentators and military bloggers, two other themes emerge: 1) Russia makes advances at the front; and 2) Russia is vulnerable in its rear to long range Ukrainian strikes. These bloggers show a renewed confidence. They believe that Russia has regained the military initiative and advantage from the low point of 9 November Kherson “regrouping” announcement. Slow advances towards Bakhmut, it is argued, are not only proof positive of this proposition, but also demonstrate that Gen Surovikin’s recommendation, accepted by Defense Minister Shoigu, was the right one, as it allowed Russian troops to withdraw to more defensive lines in the south and be redeployed to focus on expanding Russian territorial control of Donetsk region. Shortages of artillery munitions, this narrative argues, can and are being addressed. Newly mobilized and better trained battalions will be ready for a “Spring Offensive.”

The sense that time is on Russia’s side and that Russia’s military position is sustainable has taken hold. Three months into the mobilization announced on 22 September, we can see that overall it is having an effect: 50,000 are deployed, 250,000 to be deployed, and the annual autumn draft generates another 100,000. These conscripts can only be deployed to Russian territory – which, in Russia’s eyes, includes occupied Ukraine. In reality, though, Russia continues to overestimate its own ability and underestimate Ukraine’s ability, and so miscalculates the balance of forces. Differences are most stark in logistics, with Russia’s logistical supply chains broken. It is also very apparent that production in Russia’s defense industrial complex is very dependent on western component parts. Ten months into the war the Russian military has more able-bodied men, but these new forces have less armor, heavy weapons, and military equipment available to them. Russia is not ready to repel a Ukrainian winter offensive.

Repurposed Ukrainian Soviet-era targeting drones are successfully, if symbolically, capable of attacking 1000 km into Russia’s rear. The direct attack on a part of Russia’s nuclear triad (Russian strategic bombers at Engels airbase) is an unprecedented event and the expectation among commentators and bloggers was Russia would launch a very punishing response. This has yet to occur. In addition, the perception holds that Ukraine received the green light from the Pentagon to launch the attack, used western supplied long-range missiles, and received western targeting aid. Such targeting, the perception holds, was also in evidence in attacks on Saki airfield and Sevastopol in Crimea, the Moskva cruiser, Kerch bridge, and Wagner PMC HQ in Luhansk. Another concern expressed is in the decline of the supply of Iranian drones for swarm attacks against Ukraine.

By some estimates, there is a 20-30% probability that Ukraine could launch an offensive in Zaporizhzhia region around late January-February 2023, but this would likely consist of gradual advances, both in order to reduce combat fatalities and because more robust Russian defenses make the kind of collapse that occurred in the Kharkiv region in September relatively unlikely. Ukraine’s military enjoys much better morale, winter warfare equipment, and logistical supplies (in part due to shorter lines of communication). Russian missile attacks against civilians in cities force Ukraine to deploy its air defense to protect cities, opening the possibility that Russia deploys its air force against Ukraine’s military on the front lines, making continued western air defense assistance and support more generally a priority. Ukrainian morale remains high.

Continued European Solidarity?

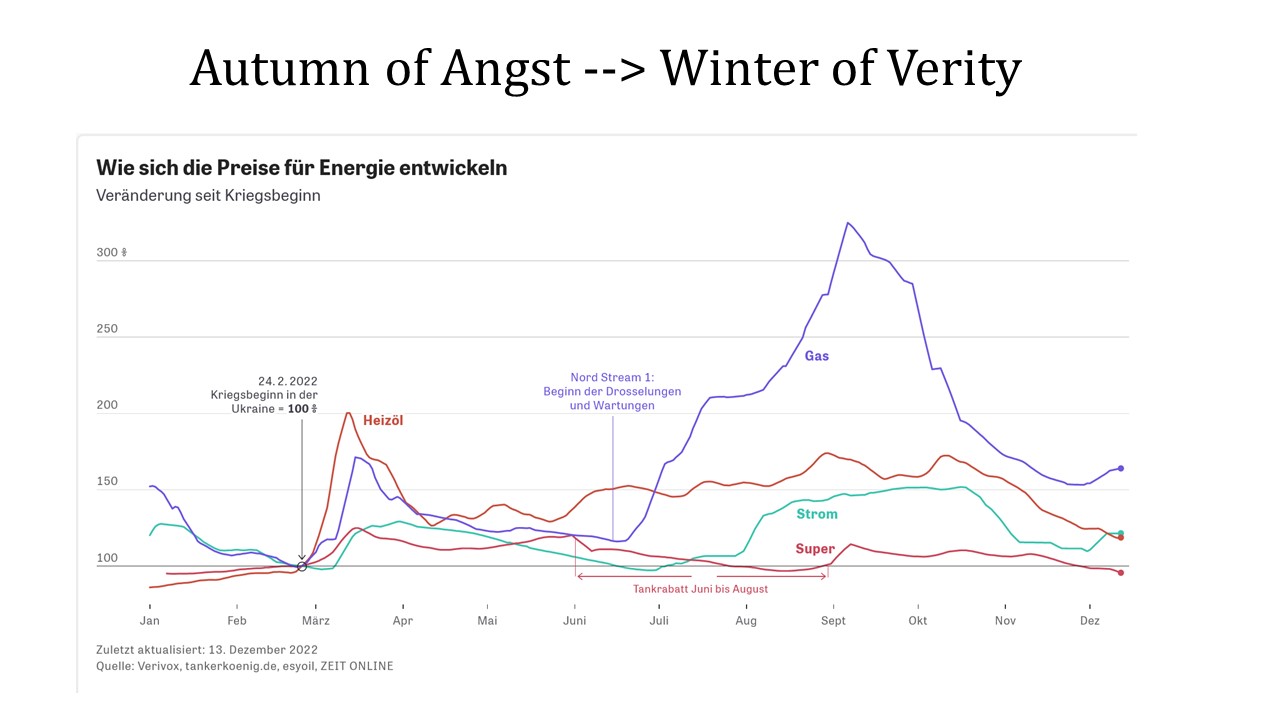

Europe faces an unprecedented energy crisis as Russia supplied 25% of its crude oil, 40% of its gas supply, and 50% of coal deliveries. Expectations around the potential magnitude of the crisis have not been met: the current situation is better than expected. Gas storage in Germany, for example, is at 90%, electricity supply is stable, and gasoline cheaper now than before the conflict (see chart below).

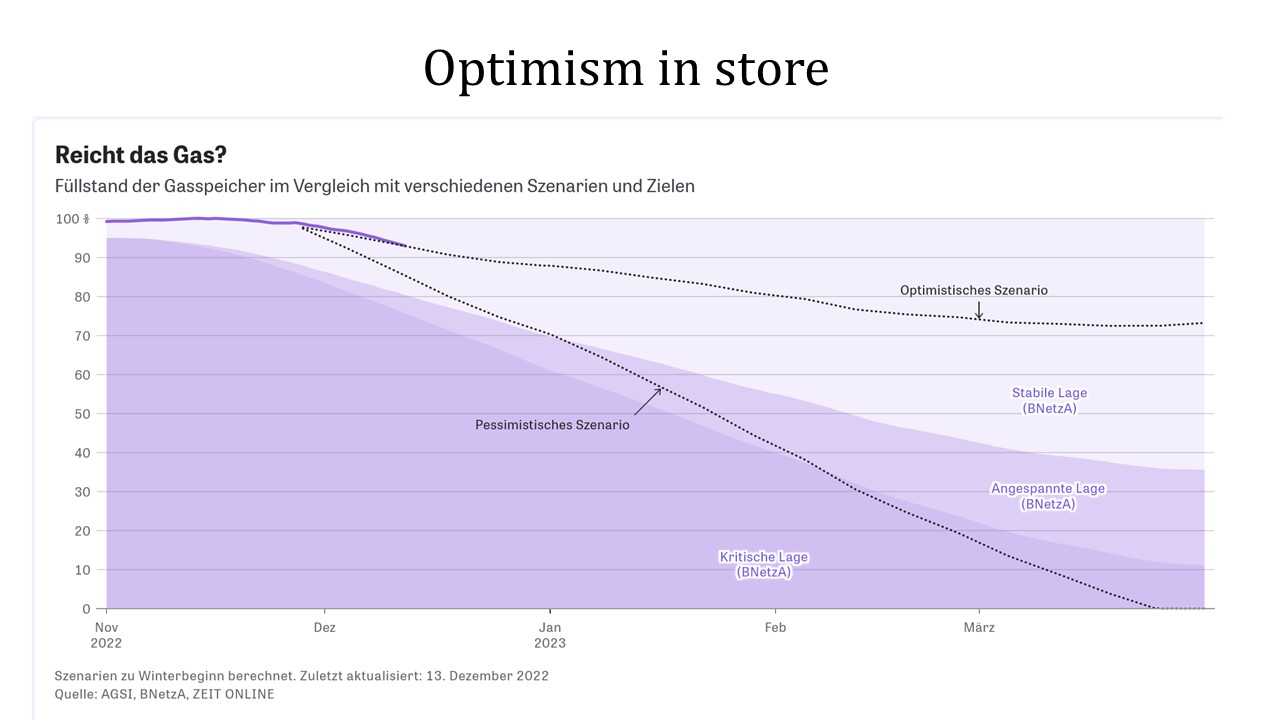

Although it is still early in the winter, we do have data and scenarios that indicate a high probability that there will be no shortage (see chart below).

A number of explanations account for this better than expected outcome. First, the EU’s energy market has functioned well, reducing consumption and bringing new energy to Europe. Second, luck with external conditions is a factor, including both the weather and a drop in Chinese consumption. Third, with few exceptions, the alignment of EU and national energy policies have prompted the filling of storages, commitments to energy conservation, and the construction of new infrastructure. In a milestone achievement, the first ever LNG shipment (“Esperenza”) docks in Germany on 15 December 2022.

How can European populations and businesses be protected from the impact? The impact feels very different in different parts of Europe - depending on energy systems, industrial consumption, and most importantly, the fiscal ability of a state to shield its consumers. Despite policy not advancing in some areas, such as a gas price cap, heated bargaining and accusations, energy has not led to deeper divisions. Why? First, it is abundantly clear that what is at stake is extremely important. As a result, attempts to divide the EU at this critical time run the risks of paying a high political price. Second, the process of advancing energy policy is characterized by lots of bargaining, over, for example, sanctions, price caps, and subsidies. In this process, there is no single East-West, core-center, North-South cleavage in Europe but rather overlapping coalitions which generate stability.

How is societal cohesion impacted? It is difficult to measure social cohesion, though protest can serve as an indirect indicator. In Prague in late October 2022 a protest gathering of 70,000 proved to be an outlier. In Germany, for example, there has been no large protest and support for the political party ‘Alternative for Germany’ peaked on this issue in October, when uncertainty and fear was at its highest. Lower gas prices and distractions, such as the World Cup football tournament and Christmas, are also factors. Attitudes, however, could change quickly. An unpredicted disaster, an attack by Russia on Norwegian pipelines, or a freak event generated by a system stretched are all possible. In addition, Russian disinformation targeting Ukrainian refugees and host state populations may be a factor, particularly following a potential upsurge in refugees over winter if the Ukrainian energy grid collapses.

In the case of Germany, it is clear that this is Putin’s war and that blame for subsequent energy disruption is easily attributed. For this reason, energy will not be the factor that results in a trade “land for peace” compromise, allowing Russia to reconstitute its military, consolidate political control, and perpetuate the conflict at a time of its choosing. In Germany, entrenched pacifism or fear of escalation (the issue of supplying German tanks to Ukraine is a case in point) could become problematic.

Winter Stalemate and Ceasefire?

Better than expected energy policies have mitigated the risk that “General Winter” would build western pressure that pushes Ukraine to accept a ceasefire on Russian terms. There is no prospect of peace talks this winter between Russia and Ukraine, but there is still a lot of talking going on. There are talks about talks, there are various talks about concrete issues that may have a wider impact on the conflict, and there are talks about avoiding escalation. There is therefore a gradual institutionalization of contacts, negotiated POW exchanges, local ceasefires, and vested interests in play that complicate the picture.

Talks about talks: A flurry of discussions in the media about talks in November may have proved divorced from the reality on the ground, but they did reflect real anxieties in the West about how to support Ukraine if the war dragged on through 2023. The New York Times, for example, reported different views on peace talks being aired inside the White House. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen Mark Milley’s suggestion in November that Ukraine should be ready to contemplate negotiations with Moscow to consolidate its current gains on the ground met with a frosty response in Kyiv.

Ukraine’s position: Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Zaluzhny responded that “The Ukrainian military will not accept any negotiations, agreements or compromises” and named the Ukrainian condition for negotiations - the withdrawal of Russian troops from “all captured territories.” As Zaluzhny’s comments suggest, Ukraine’s military leadership has no interest in talks which would likely only consolidate Russia’s territorial gains, and public opinion is supportive: at least 70% of Ukrainians want to continue to militarily resist Russian aggression. Ukraine believes it has a viable military option to end the war on its terms. But there are evidently different views in Kyiv. Although the maximalist public position - including the return of Crimea - is becoming difficult to step back from, in negotiations Ukraine could shift positions. Indeed, under pressure from Washington, President Zelensky has put more effort into a diplomatic track. He presented a 10-point peace plan at the G20 and has called for a Ukrainian Peace Formula Summit. Although the plan was largely a restatement of Ukraine’s war goals, it demonstrated an understanding of the importance of a political track. Ukraine is now trying to build on its proposals to conjure up more support - both in the West to help it survive the winter - and in the global south, where Ukraine recognizes Russia’s narrative has had some cut-through.

Russian position: Despite Russian rhetoric about being ready for talks, in reality Moscow only wants talk on its terms. An effective precondition for Russia is at a minimum de facto recognition by Ukraine of Russia’s existing territorial occupation. Speaking at a recent summit in Bishkek, Putin agreed that there would one day be a political settlement, but added that “all participants in this process will have to agree with the realities that are taking shape on the ground.” This sentiment was reiterated by Putin’s press spokesman Dmitry Peskov on 13 December, when he rejected Zelensky’s peace proposal and insisted that Ukraine must accept new “realities.”

Russia seems to believe that its aerial campaign against Ukraine combined with declining support from the West will eventually lead to talks on its terms, involving territorial concessions by Kyiv and the acceptance of constraints on a future Ukrainian state’s foreign, defense, and domestic politics. Broadly speaking, Russia sees time on its side and predicts that in 2023 it will be much harder to sustain financial support to Ukraine. Eventually, Ukraine will crack.

But behind this unrealistic view there are signs of splits in elite opinion. The so-called patriotic camp appears to be increasingly divided about how to go forward. One wing of this camp is still hoping for various types of escalation to force Ukraine to capitulate - or just collapse - but there are also signs of a more realistic appraisal from some in the patriotic camp. This group accepted the military necessity of the withdrawal from Kherson and now advocates a resigned position of defending what Russia has already seized, while focusing attention on building up Russia’s defense and economy at home.

Zaporizhzhia. Even if talks about a peace deal are unlikely, there are few other channels opening up to discuss how to manage different aspects of the war. An example is the Zaporizhzhia power plant, where IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi has been mediating talks between the two sides over establishing a “protection zone” around the plant. In theory, some kind of de-militarization of the site is possible but so far Russia has refused to withdraw its forces. Neither side trusts the other - and both have principled objections to any agreement that delegitimizes their territorial claims. The dispute is a microcosm of a wider dilemma for Ukraine. Any agreement on a protection zone around the plant that leaves Russian forces in place is a de facto ceasefire that legitimizes the Russian presence and allows them to consolidate control.

Ammonia for prisoners. Zaporizhzhia is not the only behind-the-scenes negotiation. Russian and Ukrainian delegations met on 17 November in Abu Dhabi to discuss resuming the export of Russian ammonia along a Soviet-era pipeline from Togliatti in Russia to Odesa (exports were halted after the war began) in exchange for a return of POWs. Russian ammonia exports were included in the grain deal agreed in July between Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, and the UN, but Ukraine is reluctant to allow Russian business to earn huge profits from ammonia exports through Odesa while Russia continues to bomb the city. These talks have not reached any agreement yet, although there were further prisoner exchanges on 1 and 6 December.

Conclusions

While the conflict is “mutually hurting,” a stalemate is not in evidence. A prolonged war of attrition by drone and missile attack may appear the default pathway, but it is not the only one. Putin has to escalate not to lose and Russian “victory-at-any-costs” rhetoric and targeting of cities and civilian infrastructure increases Ukraine’s will to resist and reject a ceasefire on Russian terms. Winter has not led to a strategic impasse. Fears of a grey-zone protracted inconclusive conflict characterized by operational exhaustion, war fatigue, and the rise of a “give peace a chance” camp in Europe are not realized. Paradoxically, a high intensity fluid deadlock is in balance at break-point.

A deterioration of Russian military leadership and poor discipline, training, and supply will generate significant impacts on Russia’s ability to generate deployable combat power, even come spring. Russia manages between 10-15 air sorties per day (a maximum of 20) which is inadequate given the scale of the conflict and does not allow aerial dominance. An opposite set of drivers appear the reality for Ukraine. Trust in the top leaders and wider Ukrainian institutions, such as the armed forces, emergency services and police, high morale, and continued support for mobilization in defense of Ukrainian statehood are all in evidence. Ukraine has western trained specialized units, much better logistical chains and western military assistance tied to an operational plan. The strength of Ukrainian air defense explains the underperformance of the Russian air force. Western solidarity is boosted by effective energy policy responses to what had been dependence on Russian energy.

As Russia perceives that time is on its side, and is using an operational pause to regroup and reconstitute its military in order to launch new offensives in the spring, the incentives for a focused Ukrainian offensive in winter increase - with the probability over 50%. Major Ukrainian military advances would dramatically alter political positions, leading not just to the replacement of Gen Gerasimov, but badly damaging the political legitimacy of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief – that is, President Putin.

GCMC, 14 December 2022

About the Authors

Dr. Pavel K. Baev is a Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). He is also a Senior Non-Resident Scholar at the Brookings Institution (Washington DC) and a Senior Research Associate with the French International Affairs Institute (IFRI, Paris). Pavel specializes in Russian military reform, Russian conflict management in the Caucasus and Central Asia, energy interests in Russia’s foreign policy, and Russian relations with Europe and NATO.

Dr. Dmitry Gorenburg is Senior Research Scientist in the Russia Studies Program at CNA, where he has worked since 2000. Dmitry is an associate at the Harvard University Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies and previously served as Executive Director of the American Association of the Advancement of Slavic Studies (AAASS). His research interests include security issues in the former Soviet Union, Russian military reform, Russian foreign policy, and ethnic politics and identity. He currently serves as editor of Problems of Post-Communism and was also editor of Russian Politics and Law from 2009 to 2016.

Dr. Janis Kluge is a Senior Associate at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in Berlin; the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. His focus is on economic development and trade in Eastern Europe and Eurasia, Russian state budget, sanctions, and Russian domestic politics.

Dr. David Lewis is Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of Exeter. David’s research interests include international peace and conflict studies, with a regional focus on Russia and other post-Soviet states. He is the author of numerous articles and books on Russia and Eurasia, including most recently Russia’s New Authoritarianism: Putin and the Politics of Order (Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

Dr. Graeme P. Herd is a Professor of Transnational Security Studies in the Research and Policy Analysis Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. His latest books include Understanding Russia’s Strategic Behavior: Imperial Strategic Culture and Putin’s Operational Code (London and New York, Routledge, 2022) and Russia’s Global Reach: A Security and Statecraft Assessment, ed. Graeme P. Herd (Garmisch-Partenkirchen: George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, 2021).

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany is a German-American partnership and trusted global network promoting common values and advancing collaborative geostrategic solutions. The Marshall Center’s mission to educate, engage, and empower security partners to collectively affect regional, transnational, and global challenges is achieved through programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 15,000 professionals from 157 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The Clock Tower Security Series provides short summaries of Seminar Series hosted by the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. These summaries capture key analytical points from the events and serve as a useful tool for policy makers, practitioners, and academics.

This Clock Tower Security Series summary reflects the views of the authors (Pavel Baev, Dmitry Gorenburg, Janis Kluge, David Lewis, and Graeme P. Herd) and is not necessarily the official policy of NATO, the United States, Germany, or any other governments.