COVID-19 and Irregular Migration in the Mediterranean

Every year, tens of thousands of men, women, and children attempt to move—from East to West and from South to North—across the Mediterranean. This year, irregular migration across the Mediterranean is taking place during an unprecedented global coronavirus pandemic. How is COVID-19 affecting this year’s Mediterranean irregular migration and what should be done to manage this migration during the pandemic?

On June 17, 2020, the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies brought together a diverse set of twelve practitioners and experts from Europe, Africa, the United States, and the Middle East to address this question. The following takeaways are informed by the discussion.

Immediate Impacts

1. “Fewer, More Desperate, and More Often Smuggled”: COVID-19 seems to be disrupting the typical annual pattern of Mediterranean migration.

Substantially fewer irregular migrants have been arriving in Europe from across the Mediterranean, and their numbers have been declining—rather than rising—going into the summer months. Facing closed borders, those attempting to make the journey have few alternatives during an economic slowdown. They are often fleeing conflict or threats to personal safety and are willing to pay exorbitant fees for smuggling services. Migrants face a dangerous sea crossing, deteriorating camp conditions, and rising smuggling costs.

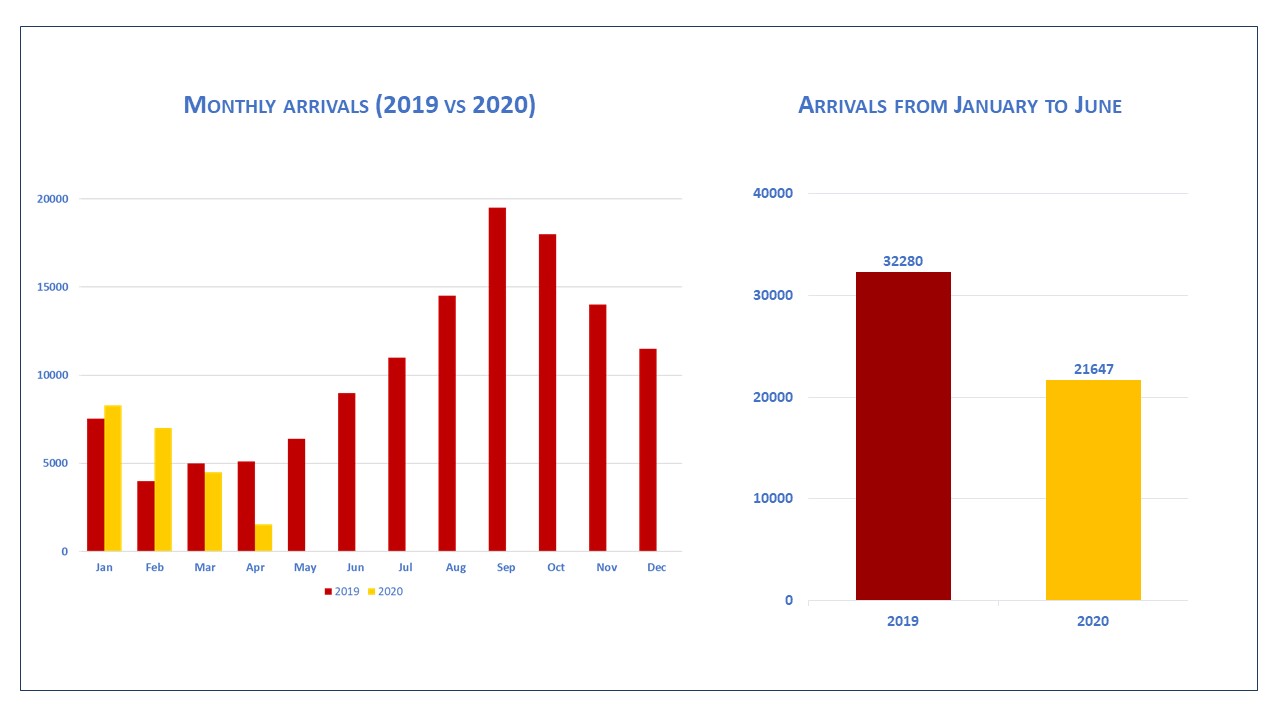

Figure 11 / Figure 22

2. Migration persists in spite of additional obstacles created by the pandemic.

Protracted conflict and failing governance in places like Syria and Libya continue to drive migrants to escape from desperate situations. Some may not know about COVID-19, despite the news and awareness raising campaigns. More likely, migrants understand the risks, but prefer to disregard them and to contravene COVID-19 restrictions. Migrants seeking security and freedom from fear will pursue safety elsewhere and are undeterred by COVID-19. Threat of infection will not stop people fleeing violence or lack of food.

3. Human smugglers and traffickers are profiting from pandemic-imposed restrictions.

Travel restrictions impede the journey to Europe, so migrants are turning to smugglers. Prices are increasing due to extra skill and effort required of smugglers, higher expenses to get through borders, and new risks associated with managing migrants who might be infected. The most desperate migrants, unwilling or unable to wait for the passage, will pay the higher costs, even by extreme means. Migrants are assuming larger debts or selling themselves into bondage in order to pay their way. Smugglers and traffickers in the Mediterranean stand to make substantial profits from the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Migrant-faring vessels present a key zone of COVID-19 contagion.

Confined spaces without social distancing, ships have proven very vulnerable to rapid COVID-19 contagion at sea. Rescue crews intercepting migrants have adopted personal protective equipment or even body suits and vessels may require sanitization procedures upon return to port. Frontline states like Malta, Greece, and Italy are ramping up interdictions, which demand increased resources. Mediterranean ports are largely closed. Disembarkation of migrants entails an obligatory quarantine period and returning migrants to unsafe conditions or conflict zones is impermissible, which leaves intercepted vessels and NGO ships in maritime limbo.

5. COVID-19 magnifies disparities in migrant center and camp management.

Migrant camps are operated by an assortment of local, national, and international actors, with varying resources and capacity. The pandemic is further congesting many overcrowded camps, which already fail to meet international standards regarding living space and adequate food. These migrant centers and camps are poorly postured to follow COVID-19 guidelines regarding social distancing and sanitation. Management demands that hygiene and disinfection tools (e.g., masks, soap, or access to clean water) are available in order to protect migrants from contagion. Infection rates will likely be reduced where transparent, responsive, flexible, and resilient management prevails, whereas the illness will likely advance where mercenary interests and corruption reign.

Protracted Effects

6. COVID-19’s prolonged impact may inaugurate a ‘new normal’ for irregular migration in the Mediterranean.

The pandemic has trapped numerous irregular migrants, and this year’s migration—perhaps merely delayed—might surge as the virus is contained. If the delay stretches into November and December 2020, however, migration may return to its annual pattern next year, with inordinate rates from May to October 2021. COVID-19’s spread and potential “second wave” will spike at different moments across Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, and governments along the migration route may make ostensibly temporary features of the COVID-19 response permanent. They might take the opportunity to retain border closures and travel restrictions. Smuggling and trafficking could then become a more prominent factor for migrants crossing the Mediterranean. Provisional shelters and makeshift accommodations for migrants may turn into permanent residences. Transit countries may become de facto destination countries that must consider integration.

7. Forces driving Mediterranean migration may intensify.

As lockdowns are lifted and economies restart, migrants who suspended their migration during the pandemic for fear of not finding work or of ending up confined within an infected European reception center may restart movement. They will be able to earn money in transit countries’ revived informal markets to cover the transportation costs, bribes, or smuggler fees for the next leg of their journey. Migrants who requested repatriation from temporary camps in transit countries for fear of infection may begin the journey anew. Countries of origin may face challenges in terms of economy (e.g., fewer remittances, reductions in public spending, recession) and politics (e.g., conflicts over closed borders, civil strife over lockdown enforcement). In turn, more migrants may flee zones with deteriorating public security and stability, and governments may even tacitly encourage migration as a social safety valve. COVID-19 could cause a systemic change in Mediterranean migration by triggering a fragile state’s collapse, leading to large-scale population displacement.

8. Migration politics risk becoming more divisive and less humane.

European governments may use COVID-19 as an excuse to crack down on irregular migration. In handling the pandemic, there is stronger disagreement over which countries should receive disembarking migrants and thereby assume responsibility for hosting them and processing their asylum claims. “Mandatory flexible solidarity,” the European Union’s latest proposal for a migration pact, would allow member states to contribute through resources rather than relocation, likely further concentrating migrants in coastal zones. Governments implement different procedures for vessels of different flag states and they regulate NGO ships domestically. European governments may retain movement restrictions and continue to “externalize” their borders, collaborating to securitize borders in places like the Sahel. Faced with tighter budgets, European governments may adopt harsher policies toward migrants, whom they cast as a burden on their domestic systems. Mainstream politicians are already adopting language from fringe anti-immigrant parties, accelerating a shift in public attitudes toward nativism and migrant xenophobia.

9. Contagion responses should deliberately shape the long-term irregular migration environment.

Governments have a continuous duty to rescue from sea and process migrants, especially those desperately fleeing in spite of a pandemic. Migrant health care is a human security priority. Destination and transit countries should work to safeguard migrants, provide social-psychological care, and regularize their work status in the agricultural and services sectors. Political leaders should reduce the stigma on new arrivals by negating the “invasion” and infection rhetoric around migration. Origin, transit, and destination countries remain charged to diminish the conditions that drive so many irregular migrants to make the perilous journey across the Mediterranean.

For Academic Citation

Benjamin P. Nickels and Margo Shields, “COVID-19 and Irregular Migration in the Mediterranean,” Marshall Center Perspectives, no. 14, June 2020, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/perspectives/covid-19-and-irregular-migration-mediterranean-0.

Notes

1 UNHRC, Regional Bureau for Europe, “Europe Situations: Data and Trends: Arrivals and Displaced Populations,” April 2020, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/76334.

2 International Organization for Migration, “Missing Migrants: Tracking Deaths along Migratory Routes,” https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean.

About the Authors

Benjamin P. Nickels Ph.D. is course director of the Europe-Africa Security Seminar and professor of international security studies. Prior to joining the Marshall Center in 2018, Dr. Nickels was academic chair for transnational threats and counterterrorism at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Dr. Nickels’ research focuses on political violence, displaced populations and migration, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, and security cooperation in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. He has served as a Fulbright scholar in Morocco and a Chateaubriand fellow in France. He holds a doctorate with distinction in history from the University of Chicago.

Captain Margo Shields is a European Command Foreign Area Officer. She received her commission from the United States Air Force Academy. Capt Shields served in various capacities with leadership success and job knowledge across joint logistics, program management, sustainment, readiness, acquisition, foreign military sales, special operations (domestic and international), interagency missions, multi-national objectives, fiscal planning, executive/VIP support, and partner-nation advising. Prior to her present duties, she worked as a Movement and Transportation Staff Officer for the NATO Force Integration Unit in Riga, Latvia and as the interim Public Affairs and Strategic Communications Advisor to the Commander.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 14,000 professionals from 156 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The articles in the Perspectives series reflect the views of the authors and are not necessarily the official policy of the United States, Germany, or any other governments.