The Causes and the Consequences of Strategic Failure in Afghanistan?

Executive Summary

- In a strategic shock, the Taliban in Afghanistan entered Kabul on August 15, following a cascading crisis triggered by Western military withdrawal, the government and Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) unwillingness to fight and the Taliban’s will to power. Structural explanations for the collapse include mission creep resulting in unattainable strategic goals and the inability of regional actors to effectively and positively support the stabilization of Afghanistan.

- The Taliban’s takeover appears to constitute a clear-cut strategic failure for the U.S. and NATO, when calculated in terms of “blood and treasure” costs as set against benefits and potential future threats. It marks the failure of Western state building efforts, and appears to signify a watershed moment for Pax Americana. Embedded in these narratives are assumptions which this paper makes explicit and subjects to critical stress-testing.

- Afghanistan will only stabilize if front-line regional powers - Iran, China, Russia, the five Central Asian states, India and Pakistan - engage positively and constructively with an Afghan government that has greatest internal legitimacy. As yet, it is unclear whether the “Taliban 2.0” is a more moderate iteration of its first incarnation or if regional actors will more effectively help stabilize Afghanistan, though they are incentivized to do so given their core national interests are at stake. A “strategically ruthless” U.S. can now reset its foreign policy to advance strategic competition with China and Russia in more important geographies and contexts, alongside friends and allies. Such a reset would be clearly reflected in the new U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) and National Defense Strategy (NDS), expected 2021-2022.

Introduction

In early August 2021, Afghanistan’s former Foreign Minister Mohammad Haneef Atmar summarised the international community’s efforts to stabilize Afghanistan over twenty years: “What was the outcome? To be fair, they restored the entire state system that was completely destroyed by the Taliban: There were no police, no army, no public administration or social services. The entire Taliban government’s health budget was about $1 million a year -- less than that of any small non-profit organization working in this area in Afghanistan. There was no state.”1 Afghanistan, the minister argued, was immeasurably improved from September 10, 2001, when the Taliban controlled 90% of the territory and were on the verge of seizing the Panjshir valley, having just assassinated Ahmad Massoud.

However, with the fall of all regional provincial capitals to Taliban forces from August 6 through to August 16 when the Taliban entered Kabul, the spectre of Afghanistan as a failed state looms large. Under such a scenario, Afghanistan will once again generate and export poverty, refugees, radicalism, and opium. Approximately 30,000 Afghan citizens have been leaving Afghanistan through August, the majority travelling to Iran or Pakistan by land, with half-a-million IDPs and Europe fearing: “a repeat of 2015 and early 2016, when more than 1 million migrants, mostly from Syria but also Afghanistan and Iraq, arrived in Europe, sparking political turbulence within member states and across the bloc.”2 As Western foreign aid is reduced and the IMF blocks the Taliban’s access to $460 million in currency reserves, the Taliban will look to alternative sources of finance, incentivizing opium production and export.3 At the same time, supportive jihadi extremist narratives from Kano to Khartoum and Kabul to Kashgar are boosted by the Taliban takeover. Afghanistan could, under a “Taliban 2.0” regime, amplify “the spirit of defiance and steadfastness among China’s oppressed Uighur Muslims, and reviving the spirit of jihad among Chechnya’s Muslims who still dream of independence from communist Russia.”4

The strategic shock of the sudden collapse of western supported order in Afghanistan promotes snap and stark judgements in the international media and commentariat. One theme is a stain on the Biden administration: “Joe Biden has defined his presidency with the most disastrous American foreign policy decision since the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The only thing worse than a ‘forever war,’ as Biden has called the Afghan conflict, is a ‘forever defeat.’ He has delivered that.”5 Another theme is a more general negative judgement on U.S. post-9/11 foreign policy: “America’s 20-year-old “War on Terror” is the greatest strategic disaster in the country’s modern history. It should never have been fought.”6 A third theme widens the aperture further and argues that the fall of Kabul, in fact, marks a paradigm shift in global order: “This is a watershed moment that will be remembered for formalizing the end of the long-fraying Pax Americana and bringing down the curtain on the West’s long ascendancy.”7 Such a sentiment is especially, but not exclusively, promoted by adversaries of the United States: Russian Senator Alexei Pushkov frames the fall of Kabul as the “revenge of history, religion and ideology over modernity and globalism” and “the decline of a whole school of thought, a whole system of myths and ideas” about the ‘end of history’ and the triumph of the Western model.8

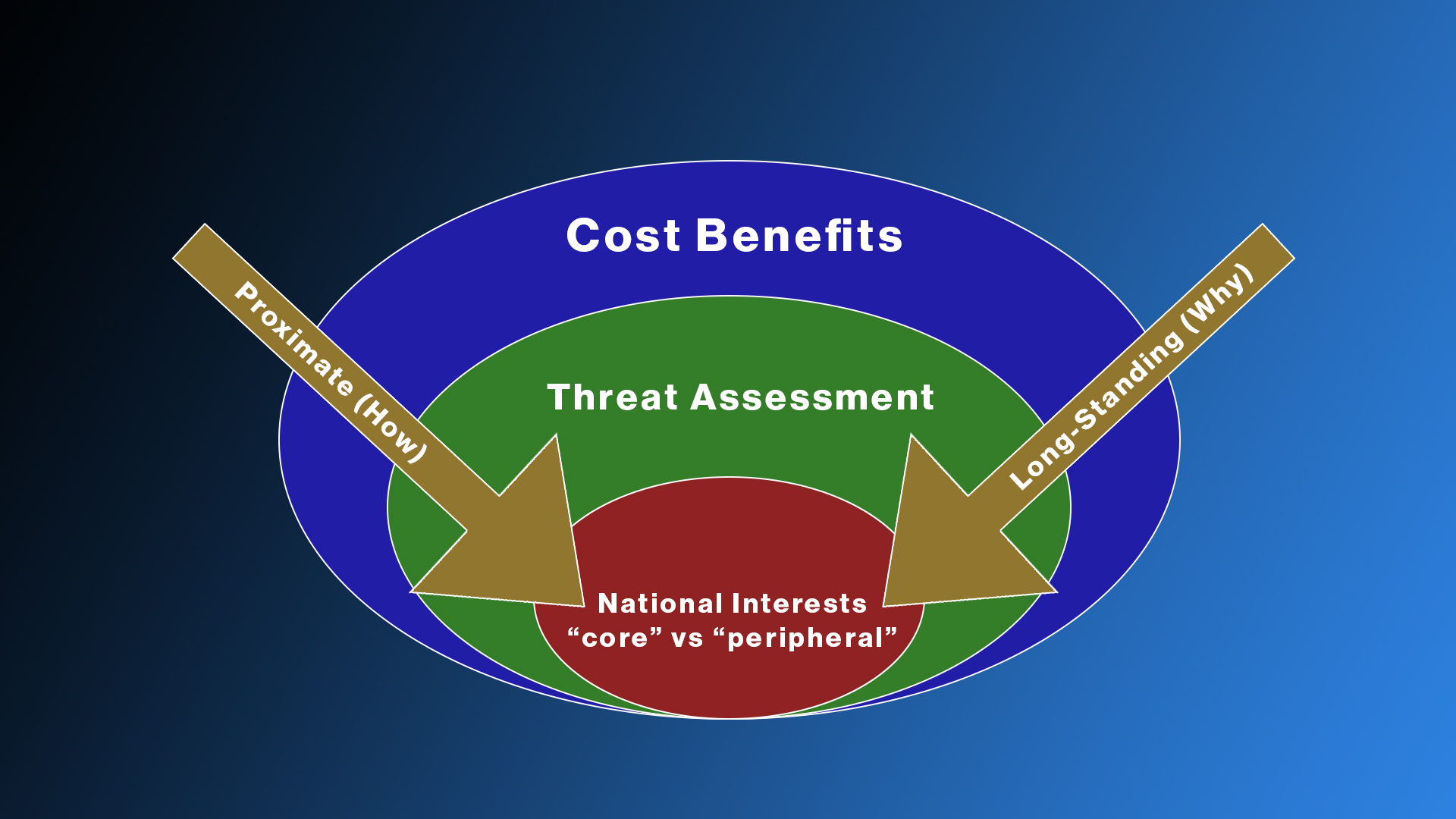

This short paper attempts to survey key assessments of the causes and consequences of strategic failure. Any assessment made within a week of the collapse must, by definition, be speculative. Nevertheless, even an initial assessment can recognize that to identify and draw the right lessons we must first ask the right questions. To that end, the paper examines the proximate and long-term explanations for the cascading collapse, focusing on how (the proximate causes) a cascading collapse withdrawal took place and why (the longer-term structural causes). It then identifies three different understandings of what constitutes “strategic failure” and the necessary conditions present in each: a costs/benefits analysis approach; a threat assessment-based approach; and, a peripheral vs core national interest approach.

What were the Causes of the Cascading Collapse of the Afghan Military and State?

In addressing this question, we can look at proximate and longer-term causes. In terms of proximate causes, we can identify the U.S. agreement with the Taliban in 2020, the nature of its actual implementation in 2021, and the Taliban’s ability to coordinate a lightening takeover. When we examine longer-term causes, we can identify post-9/11 mission creep that resulted in unattainable strategic goals, the failure of the Afghanistan government over twenty-years and the inability of regional actors to effectively and positively support the stabilization of Afghanistan.

The Doha peace process and agreements made with the Taliban negotiators was enabled by the Taliban first opening a Qatar representation office in Doha in 2013. In February 2020, a United States-Taliban bilateral accord released 5,000 Taliban prisoners and set May 2021 as a deadline for the withdrawal of remaining U.S. combat troops, and in return the Taliban did not target U.S. troops in Afghanistan (who reported no combat fatalities since the accord), and agreed to cut off links with al-Qaeda and any other transnational jihadist groups. As the Afghan government was excluded from the accord its standing was undercut, providing the Taliban with momentum and the appearance of having secured a diplomatic victory. The Biden administration inherited and chose to adopt this accord, though in April 2021 extended the troop withdrawal deadline to July 4, 2021. President Biden justifies the rationale for withdrawal as follows: “Over our country’s 20 years at war in Afghanistan, America has sent its finest young men and women, invested nearly $1 trillion dollars, trained over 300,000 Afghan soldiers and police, equipped them with state-of-the-art military equipment, and maintained their air force as part of the longest war in U.S. history. One more year, or five more years, of U.S. military presence would not have made a difference if the Afghan military cannot or will not hold its own country. And an endless American presence in the middle of another country’s civil conflict was not acceptable to me....We gave them every tool they could need. We gave them every chance to determine their own future. [What] we could not provide them, was the will to fight for that future.”9 The cascading collapse of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and the Afghan government reaffirms this assessment.

To expedite the withdrawal, Bagram Air Base, the military hub of major military operations in Afghanistan, was “handed over” to Afghan authorities on July 4. On July 8, President Biden suggested that the Afghan government was unlikely to fall and that there would be no chaotic evacuations of Americans similar to the end of the Vietnam War. However, the withdrawal of all U.S. forces had three immediate and apparently unanticipated consequences. First, the last remaining 3,000 U.S. troops anchored the 8,500 troops of allies, and as the U.S. withdrew, so did allies and with them the thousands of contractors who kept the Afghan air force flying. Second, the psychological impact on the ANSF was profound: “The ANSF were built to operate within the framework of coalition support that was available for most of the past decade—high levels of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information coupled with rapid close air support and contractor support for logistics and maintenance. Once that framework was removed, the ANSF no longer had a method of fighting the Taliban that worked, and were without the assured backing of U.S. and NATO power.”10 As a result, and third, U.S. “Operation Allies Refuge” was overtaken by events. The special immigrant visa system broke down. America’s Afghan allies (interpreters, translators, analysts) and their families and former Afghan government, military and secular civil society (especially female judges, police officers11 and human rights activists) were perceived by a victorious Taliban as “traitors.”12 Accusations of intelligence failure, the lack of contingency planning, “fiasco” and “professional malpractice” characterized commentary.

The actions of the Taliban itself is clearly relevant. Their lightening advances, especially from August 6 to 15, can be explained through deals made at local level between the Taliban and ANSF commanders, brokered by community leaders to avoid civilian casualties. This led to accusations of inter-ethnic collusion between President Ashraf Ghani, the Afghan National Security Council under his leadership and the Taliban.13 A contrast became apparent. On the one hand, the Afghan government was characterised by self-interest, corruption, electoral fraud, limited local legitimacy, and led by an isolationist and polarizing president. On the other, the “Taliban 2.0” had mastered psychological- and information operations, “able to successfully exploit the foreign presence by making their fight not only an Islamic but also a nationalist cause... Patriotism often trumps ideological differences and even the quest for individual liberty.”14 In addition, the Taliban’s concerted efforts over the last decade to gain non-Pashtun participation (Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kazakh minorities) through a strategy of co-optation had some effect.

While short-term factors focus on the agency of the United States, the ANSF and government and Taliban agency, longer-term explanations are rooted in the determining influence of structural factors on the nature of governance in Afghanistan. Here it is argued that the objective of creating a centralized, unitary, and modern state was an unattainable goal: “The country’s difficult topography, ethnic complexity, and tribal and local loyalties produce enduring political fragmentation. Its troubled neighborhood and hostility to outside interference make foreign intervention perilous.”15 The Afghan state’s historic weakness was reflected in the inability of all governments over the last twenty-years to root itself in the alienated “tribal Pashtuns (who formed the state’s essential base), as well as rural Afghans of other ethnicities.” This political failure “helped to cripple the Western attempt to create a democratic Afghan state, and opened the way for the Taliban to re-establish their own alternative model of state-building.”16

The inherent weaknesses of the Afghan state met over-stretch was compounded by “mission creep” and strategic impatience in the West. Counter-terrorism morphed into counter-insurgency, whose success was dependent on having the Afghan government as a reliable political partner. A condition that was never met. Counter-insurgency then became a “democracy-building,” “state-building,” and “nation-building” efforts, which failed to realize that embedded culture and social institutions trump western ones. Top-down state-building strategies fail in the context of “a deeply heterogeneous society organized around local customs and norms, where state institutions have long been absent or impaired.”17 In addition, much of the U.S. and other aid was misdirected. The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction reports that the U.S. “invested roughly $946 billion between 2001 and 2021. Yet almost $1 trillion in outlays won the U.S. few hearts and minds. Of that $946 billion, fully $816 billion, or 86%, went to military outlays for U.S. troops. And the Afghan people saw little of the remaining $130 billion, with $83 billion going to the Afghan Security Forces. Another $10 billion or so was spent on drug interdiction operations, while $15 billion was for U.S. agencies operating in Afghanistan. That left a meager $21 billion in “economic support” funding. Yet even much of this spending left little if any development on the ground, because the programs actually “support counterterrorism; bolster national economies; and assist in the development of effective, accessible, and independent legal systems.” Jeffrey Sachs concludes: “In short, the U.S. could have invested in clean water and sanitation, school buildings, clinics, digital connectivity, agricultural equipment and extension, nutrition programs, and many other programs to lift the country from economic deprivation.”18

Defining Strategic Failure

There is no consensus as to what characterizes strategic failure. As noted above, this paper addresses three alternative understandings of what constitutes “strategic failure” and the necessary conditions present in each. First, a broad “blood and treasure” costs/benefits approach is our focus, which includes reputation and credibility diminution in the “treasure” spent column. Second, a more narrowly prescribed threat assessment-based approach is examined. Does withdrawal necessarily allow for and enable the emergence of the threats that drove intervention in the first place? Third, and more paradoxically, are we witnessing a “win the battle, lose the war; win the war, lose the peace” moment? In other words, does the U.S. have to lose a peripheral interest in order to reset foreign policy and “win” on issues and concerns of core national interest, not least strategic competition with Russia and China? Again, though it is only ten days after the fall of Kabul and judgment must necessarily be speculative, it is not too early to offer initial thoughts and to begin to frame the discussion.

Costs and Benefits Assessment: “What price blood and treasure?”

From the perspectives of “blood and treasure” expenditure and costs when calculated against stability benefits and returns, Western intervention in Afghanistan can be judged to be a collective strategic failure. The costs or “inputs” can be easily identified: twenty-years and “$2 trillion and close to 2,500 American lives, over 1,100 lives of its coalition partners, as well as up to 70,000 Afghan military casualties and nearly 50,000 civilian deaths.”19 The U.S. and allies funded approximately 80% of Afghanistan’s budget and in 2020 foreign aid constituted 43% of its GDP. The withdrawal also appears as a reputation-sapping April 1975 “Saigon moment,” damaging the image of U.S. strategic competence: “Untrustworthy, unreliable, disloyal. It must surely carry a message, a predilection to not follow through that which was promised, a defeat not only militarily but of professed values.”20 More generally, commentators question the cohesion of the NATO alliance, defeated as it has been by jihadi forces: “America’s strategic and moral failure in Afghanistan will reinforce questions about U.S. reliability among friends and foes alike.”21 Lastly, it reinforces Russian and Chinese great power competition narratives around changing global order: “Kabul’s fall seems to become a tombstone on the grave of American messianism, the idea that America brings the rays of freedom, democracy and progress to the rest of the world.”22

First and foremost, for the U.S. the debate of the fallout is internal to the U.S. military. For some commentators, the precipitous withdrawal reality undercuts the “we plan for everything” mantra and highlights a U.S. military culture flaw - the inability of the U.S. military leadership to speak truth to power. The withdrawal will make many currently in the military and perhaps especially veterans, whose professional experience has been defined or shaped by Afghan deployments, demoralized and questioning of their civilian leadership and even core national values and ideals. What are core values, how are they upheld and are there consequences for failing to uphold them?23

From key U.S. NATO allies, the assessments are stark. In Germany, Armin Laschet, German Christian Democratic Union party leader and Chancellor-candidate to succeed Angela Merkel, concluded that the entire Afghanistan operation was a failure and that the withdrawal “the biggest debacle that NATO has suffered since its founding.”24 Norbert Röttgen, the chairman of the German parliament’s foreign relations committee: “This does fundamental damage to the political and moral credibility of the West.”25 Cathryn Clüver Ashbrook, director of the German Council on Foreign Relations, argues that: “The Biden administration came to office promising an open exchange, a transparent exchange with its allies. They said the transatlantic relationship would be pivotal. As it is, they’re playing lip service to the transatlantic relationship and still believe European allies should fall into line with U.S. priorities.”26

In the UK, Lord Peter Ricketts, the UK’s former national security adviser, commented: “It looks like NATO has been completely overtaken by American unilateral decisions. First of all, Trump’s decision to start talking to the Taliban about leaving and then the Biden decision to set a timetable. The Afghanistan operation was always going to end some time, it was never going to go on forever, but the manner in which it’s been done has been humiliating and damaging to Nato.” Lord George Robertson, NATO secretary-general at 9/11: “It weakens Nato because the principle of ‘in together, out together’ seems to have been abandoned both by Donald Trump and by Joe Biden.”27 Rory Stewart, a former British cabinet minister with lengthy experience in Afghanistan: “He hasn’t just humiliated America’s Afghan allies. He’s humiliated his Western allies by demonstrating their impotence.”28

According to Russian and Chinese controlled media and officials, the U.S. withdrawal demonstrates failure and unreliability, with the understanding that the U.S.’s support for Afghanistan is fickle, as will its support for Ukraine and Taiwan. This sentiment is actively promoted by Nikolai Patrushev, Secretary of Russia’s Security Council.29 China argues that U.S. promises to Hong Kong democracy activists are “unreliable as the U.S. “abandons allies.” Peter Jennings suggests that “political disarray” in Washington might be “the right time for China to press its confected claims over Taiwan.”30 On August 16, China’s Global Times called the:

Afghan abandonment a lesson for Taiwan’s independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government. From what happened in Afghanistan, they should perceive that once a war breaks out in the Straits, the island’s defence will collapse inhours and the U.S. military won’t come to help. As a result, the DPP authorities will quickly surrender, while some high-level officials may flee by plane.31

The Beijing-friendly Taiwan newspaper United Daily News argued public opinion in Taiwan had felt the shock of Biden’s Saigon-like “abandonment” of Afghanistan. It called on Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen’s DPP government to be wary of “tying the lifeline of Taiwan’s national security and survival to the U.S.” as an “anti-China pawn.” On August 17, its editorial noted: “It could be Afghanistan today, Taiwan tomorrow.”32

However, these sentiments, though heartfelt, were immediate reactions to unfolding events. Another understanding picks up on the withdrawal as a sign of U.S. strategic ruthlessness: “Afghanistan is a reminder that the U.S. is a ruthless power and ally with a stark calculation of its interests. This is a lesson for allies and adversaries equally.” The “lessons” drawn from this identified trait and characteristic have different implications for NATO: “A key message from the U.S. is that it is much more likely to support allies who are capable. It will help those who help themselves—and who can make useful contributions to U.S. interests.”33 European NATO is forced to recognize that U.S. security guarantees are time limited. As a result, European NATO needs to look again at NATO’s deterrence capabilities and Europe’s strategic autonomy: “A key lesson from Afghanistan for America’s allies is that we all need to strengthen our own defence capabilities. We cannot assume that the U.S. will just be over the horizon ready to defend our strategic interests.”34

If we cast our net wider to include other friends and allies, we can note that in Ukraine, the withdrawal is understood as a sign that Ukraine must rely on its own army and root out corruption in order to withstand Russian influence: “The Afghanistan tragedy shows that if an ally is not ready to fight for itself, Americans will not bother.”35 Similarly, the Kabul catastrophe is understood as a reminder to South Korea and other U.S. allies that its decades-old security commitments should not be taken for granted as U.S.’ may engage only where vital interests are at stake. “It sends the message that Washington, with its finite power, cannot help but make a decision prioritising U.S. interests, and that it can withdraw needless intervention or investment anytime if allies do not have the capabilities or will to fend for themselves.”36 In Israel, while hawks argue that the U.S. cannot be relied on to guarantee the security of the state,37others suggest that U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan will prompt Israel and Arab countries to form a regional alliance to protect the interests of both sides.38

Threat-Based Assessment: “Back to the Future?”

A threat-based assessment approach could argue that costs aside, the core benefit must be that the threats which the post-9/11 intervention were designed to eliminate were successful. According to this “back to the future” reading, Western strategic failure is not rooted in an inability to create a stable modern functioning democratic state. Strategic failure only occurs if the strategic threats that justified the strategic intervention after 9/11 are more likely to occur as a result of the withdrawal than before the intervention. Thus, return of “Taliban 2.0” can be considered a necessary but not sufficient condition to meet this definition. If Afghanistan becomes an ungovernable failed state and a breeding ground for terrorism, with “Taliban 2.0” unable or unwilling to prevent al-Qaeda or an al-Qaeda type entity, such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), the Pakistan-based Haqqani Network (HQN) or ISIS-Khorasan (IS-K) from planning and executing strategic strikes against continental United States, strategic failure will undoubtedly have occurred.

This outcome is based on three core assumptions. The first assumption is that the Taliban can not only take power and control most of the territory, but can hold power and exercise it: “Taliban 1.0” was never able to govern, just through coercive force to impose their will on the population. To hold and exercise power suggests that the Taliban is unified and governs as an institutionalized entity, which in turn supposes that it is able to more broadly reflect Afghan society than its first iteration 1997-2001. There is some evidence of apparent change in behavior. Siraj Ul Haq, head of the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), notes that the Taliban’s announcement for general amnesty, non-retaliation against opponents and protection of diplomats and foreigners is “unprecedented in modern history of the world.39 “Taliban 2.0 is undoubtedly better than “Taliban 1.0” at strategic communication, better able to project itself as a mature political entity. Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid has said that the group wants friendly relations with countries around the world and international recognition: “The world should not be afraid of us. We must be recognised. We want friendly relations with all countries of the world, including the United States.” He also called on the people to work with the Taliban and help create an “inclusive system.40 “Taliban 2.0” is certainly better armed, inheriting Black Hawk helicopters, A-29 planes and other equipment that the U.S. has provided to the Afghan military. Can it maintain the equipment or given the need for revenue, will the arms be sold? In short, the assertion would be that “The Taliban of today is not the Taliban of yesterday. It has a local and international network of relations (the United States, Russia, China, Iran, and Qatar) and is more realistic than before. … It will thrive if it evolves, and perhaps it will establish a regime that treats women like the Iranian and Saudi regimes, which are both internationally recognised.”41

The core indicator of positive change within “Taliban 2.0” will be found not just in what it says, but what it does, in reality and not rhetoric, as words are not a good predictor of future Taliban action. Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, the head of the Taliban’s military commission, released an audio message ordering the group’s fighters to not enter homes and seize properties in Kabul: “We want to message and instruct the esteemed mujahideen that nobody is allowed to enter anybody’s homes, particularly in Kabul where we have recently entered. They are also not allowed to seize anybody’s vehicles... We will then follow up this process [collecting government vehicles] properly in the future with the help of relevant bodies. If it is money or vehicle and guns, anything, all are public properties. If they take these things or hide it, this would be considered as robbery and treason to the blood of martyrs.”42 However, reports also emerge of: “Mass killings of people, arrests, and executions of government employees in front of people, open trials of women and civil society activists, mass displacements and forced marriages of women and girls are notable examples of crimes committed by the Taliban in areas under their control. The shooting of more than 100 civilians in the town of Spin Boldak in Kandahar province and more than 20 civilians in Ghazni’s Malistan district are obvious crimes committed by the Taliban in the past month. The Taliban’s brutal killing of Nazar Mohammad Khasha, the Kandahari comedian in the Dand district of the province, drew global reaction and recreated the true face of the Taliban for the world.”43

Current moderation may just be examples of Taliban soft power and a charm offensive for necessary legitimation purposes. As Stefano Stafanni, former Italian Ambassador to the U.S. notes: “Thousands of citizens in Jalalabad and in Khowst, the latter having been under the heel of the Taliban for a few days now, dared to stage street protests, which were immediately bloodily put down. None of all this was apparent in the sophisticated official voice of the regime. The charmer Zabihullah Mujahid, the spokesman of the new lords and masters in Kabul, spoke -- in good English -- to the international audience, not to the Afghans. The press conference, a masterpiece of communications, subtleties, and ambiguities, had just one purpose: to reassure the world, especially the West that is so perversely obstinate in defending human rights, basic freedoms, and the status of women, so permanently concerned over terrorist infiltration by Al-Qaeda or ISIS, that the Taliban will give the country a civilian government that is responsible and civilized.”44

The current Taliban supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, is considered to be more able than his predecessors to maintain intra-Taliban factional unity. However, the Taliban is a factionalised entity, split between, for example, Taliban ideologues/hardliners and pragmatists, with a “long history of dissention among the Quetta, Peshawar and Miran Shah shuras that direct Taliban activities.”45 There is certainly a potential struggle for re-division of spheres of influence inside the Taliban itself, compounded if regional and other powers will play on these differences. A number of other armed groups in Afghanistan may not obey the Taliban. The Hazarajat (the land of the Shia Hazara) in central Afghanistan, is not yet under effective Taliban control. Is there a new “Northern Alliance 2.0” based on non-Pashtun ethnic groups in Afghanistan, such as the Uzbeks around Mazar-e Sharif and Tajiks in the Panjshir?46 It is unclear, how much political will such proto-entities may have, or the extent to which the threat of formation is means to gain concessions from the Taliban or if splits centered on ethnicity (Pashtun majority vs minorities) is overlaid by a geographical (northern vs southern Afghanistan) division which triggers a civil war. In such circumstances, the Northern Alliance would likely receive tacit external support from, for example, Russia, India, China and Iran, while the backbone of the Taliban, the 46 Pashtun clans, would be backed by Pakistan and transnational Islamic jihad.

A key determining factor will be the strength and intent of the “Taliban 2.0” leadership and government. This in turn rests on how the Taliban approach a key dilemma that they face. The declaration of a reclusive Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (on September 11, 2021) achieves their primary strategic goal and support of Salafi-jihadi groups world-wide: “It is part of the Taliban’s ideology to reject modernism and the international community — and the reputation won by forcing the U.S. to leave is worth far more than aid budgets.”47 However, this unfolding would trigger a new protracted civil war, with the reconstitution of a Northern Alliance. Alternatively, the creation of an inclusive coalition government represented by all major political, ethnic and tribal forces in the country, would certainly gain credibility in the wider Muslim world and garner international recognition and development aid, but would it also be considered a compromise too far, causing a civil war within the Taliban itself, and between the Taliban and erstwhile external allies?

We can identify three key indicators which may suggest which way the Taliban leans. First, will the government be inclusive, to include some non-Taliban elements? The three member “Coordination Council” negotiates a “peaceful transfer” of power to the Taliban in Kabul. It includes former President Hamid Karzai, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leader the Hezb-e Islami party, and Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, the chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation (HCNR).48 Will former ANSF personnel be integrated into the new armed forces of Afghanistan, as reservists or regulars? Given tens of thousands of former security forces are without an income and likely have access to arms, this would certainly be pragmatic and inclusive. Second, can influential clerics and Taliban leaders institute Sharia laws gradually and only partially, steering some of the most controversial aspects of Salafi-Jihadi hardline Islamic doctrine and Sharia law away from the most extreme interpretations?49 Third, one very visible indicator of intent is the treatment of women, not least their access to the labor market and education and whether the Burqa (the blue garments that cover a woman’s body from head to toe), a symbol of the Taliban’s previous rule, will it be so again? Al-Arabiya TV, a Saudi-owned pan-Arabic channel (perceived to be an arm of Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy), adopts an editorial line favouring women’s rights in Afghanistan to avoid the situation where: “extremism will take over power, moderation will disappear, and darkness will replace light.”50

A second core assumption is that the there is no “Taliban 1.0” or “Taliban 2.0” – just “Taliban” and that this seemingly static and enduring entity is not a learning organization. In other words, we must assume that “Taliban 2.0” does not understand that the export of global terror crosses a threshold for response, as the aftermath of 9/11 in fact demonstrated. As a result, the “Taliban 2.0” refuses to implement a watered down version of Sharia law to appease the international community. It does welcome and shelter radical groups and the territory of Afghanistan does become a sanctuary allowing for the resurgence of transnational terrorism. Here the logic is clear: the Taliban have retaken power; so too will jihadis focused on terrorist acts against the West.51

When questioning this assumption, we can note that the Taliban does oppose and campaign against IS Khorasan Province (ISKP), each calling the other “an apostate militia,” and ISKP undertaking a coordinated media campaign online against the Taliban. With regards to Taliban-al-Qaeda relations, the picture is more ambiguous. In the Doha accord of February 2020 the Taliban publicly declared that they cut links with al-Qaeda. Although the Taliban and al-Qaeda share a religious Salafist creed, ideology and worldview, they have different objectives: “The Taliban aims to establish a theocracy, or Islamic Emirate, in Afghanistan, but has indicated no ambition to expand beyond that country’s borders. By contrast, al-Qaeda has no national identity, nor does it recognize borders. It is a borderless movement, with branches in scores of countries worldwide, that seeks to spread its ideology near and far by any means, including violence.”52

Nonetheless, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) became the first al-Qaeda group to congratulate the Taliban following its seizure of Afghanistan, praying for the success of the Taliban in establishing true Sharia rule and upholding “wala and bara” (loyalty to everything considered Islamic and disavowal of everything considered un-Islamic).53 The leader of al-Qaeda’s Sahel affiliate Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), Iyad Ag Ghaly, rallies supporters to follow the Taliban example in Afghanistan.54 The Pakistan-based Haqqani Network is considered “completely integrated with the Taliban. HQN militants often serve as the shock troops for the Taliban, while remaining close to Directorate S, the unit of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) that runs Pakistan’s clandestine relationship with the Taliban. This connection with Pakistan explains why HQN is also helping China, a close Islamabad ally, to run operations against Uyghur co-religionists in Afghanistan.”55 We can surmise that the presence and role of HQN in Afghanistan will provide a barometer of Pakistan-Taliban relations.

Our third core assumption is that if the Taliban does allow radical extremists to congregate and organize terrorists attack from within the “Islamic emirate of Afghanistan,” threatened external actors are powerless to react. CIA director William Burns notes that intelligence-gathering efforts will be more difficult without a U.S. military presence in the country. However, while this is undoubtedly true, the U.S., friends and allies have electronic surveillance/drones that can inform if al-Qaeda or equivalent entities are reconstituted. As U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken argues: “Our capacity to do that is far different and far better than it was before 9/11.”56 The U.S. does have over-the-horizon capability (the 21st century of the British 19th century “butcher and bolt” approach) from the Arab Gulf states or U.S. off-shore carriers.

However, in the post-9/11 strategic context, it is also true to note that transnational jihadism has metastasized to Sahel, Middle East and South Asia: Afghanistan’s territory is not, per se, needed for this function - 9/21 is not 9/11.57 Afghanistan does not need to become an actual physical sanctuary or haven for terrorism. It can serve as spiritual or ideological inspiration and motivation for other radical groups to follow suit.58 Jihadist groups in Muslim conflict zones such as Somalia, Mali, and Yemen hope to replicate the political and territorial gains made by the Taliban, by stepping up attacks and forcing local and international players to sit down, talk and give them concessions. As foreign troops withdraw, corrupt, poorly trained and resourced local troops can then be defeated. The “power of example” is the key to understanding the “Taliban 2.0’s” destabilization effects: emulation and replication are orders of the day.

In Pakistan, one fear is that “Taliban victory might be a morale boost for Pakistan’s version of the Taliban, Tehrik e Taliban’ [TTP].”59 In a message addressed to Afghan Taliban chief Hibatullah Akhundzada and the people of Afghanistan, TTP leader Noor Wali Mehsud, stated that the TTP would renew its allegiance to the Afghan Taliban.60 In Israel, the Islamic Resistance Front amplifies the message that ousting a major power is possible with stamina and tenacity. Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Lebanon’s Hezbollah terror group, has cast doubt on the reliability of the U.S. as a protective power in the Middle East by asking rhetorically: “In order not to have Americans fighting for other [nations], [President Joe] Biden was able to accept a historic failure. When it comes to Lebanon and those around it, what will be the case there?”61 Similarly, Hamas highlights the importance of the Taliban’s victory after a continuous twenty-year struggle and resistance: “The Taliban are victorious today after being accused of backwardness and terrorism. They emerge today as a smarter and more realistic movement. They confronted America and its agents and refused to compromise with them. They were not deceived by bright headlines about ‘democracy’ and ‘elections.’ ”62 Syria-based jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has congratulated the Taliban over its takeover of Afghanistan after the withdrawal of U.S. troops. HTS is the dominant force in rebel-held territory in north-western Syria.63

In the Sahel, lessons derived from the fall of Kabul are also being identified, not least the implications for conflict resolution. Foreign forces, not subject to local control, can withdraw. Will poor governance in the Sahel encourage the region’s al-Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates to intensify violence once foreign forces depart? Will the Mali Armed Forces (FAMa) be able to stop the threat of jihadist occupation if the forces are withdrawn? Can Islamist fundamentalists succeed in imposing their hegemonic agenda in West Africa through the creation of a full-fledged caliphate or through any other form of organised governance? The deteriorating security situation in the Sahel generates calls for the departure of foreign forces whose presence appears ineffective. Mali’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tiebile Drame, notes that: “the outcome of the war in Afghanistan should make Mali and the Sahel reflect. Especially to those who, for years, have been making the same demands as the terrorist warlords.”64 Does departure of foreign forces from Sahel create a vacuum which leads to state collapse and take over by radical forces? Sahel governments need to undertake contingency planning: “in order to avoid any unpleasant surprises from their partners, and in particular from France, whose presence is increasingly being disapproved by a large number of civil society organisations and by certain politicians.”65 Jean-Herve Jezequel, the project director for the Sahel at the International Crisis Group in Dakar, Senegal, notes that: “The events in Afghanistan give these groups [Sahel militants] hope in taking over political power in these countries. The Taliban today succeeded in imposing their authority not only through arms, but also through dialogue. The question to ask ourselves is whether the Taliban example will incite the jihadist groups in the Sahel to also engage in their form of dialogue, not only with the states in the region but also with other international partners which are militarily present in the region.”66

Strategic Withdrawal, Regional Stabilization and U.S. Foreign Policy Reset?

A third and last core assumption is time-related, suggesting that Afghanistan will only be stabilized if front-line regional powers - Iran, China, Russia, the five Central Asian states, India and especially Pakistan - engage positively and constructively with an Afghan government that has greatest internal legitimacy.67 The necessary trigger for regional engagement is a fear of destabilization and civil war and the spillover of dysfunctionality (not least, jihadism, refuges, and drug trafficking) following the sudden return of the Taliban to power after Western withdrawal. That the withdrawal was chaotic only adds to a sense of urgency in the region. With the withdrawal of the U.S. and NATO allies, Russia, China and Pakistan’s influence in the region which emerges as “as a post-Western or post-U.S. space ... It’s a region transforming itself without the United States.”68 In the heart of this proposition is a paradox: the West has to fail for the regional powers to have the opportunity and incentive to succeed. A post-American regional future is one in which the West loses leverage in Afghanistan. This forces geographically proximate stakeholders to step in to vacuum and stabilize Afghanistan, while the threat of a destabilized Afghanistan may even help stabilize neighbors.69

How have and do these regional actors engage the Taliban and why? Most actors have established contacts with the Taliban, but this does not mean official recognition of their legitimacy. Neighbours engagement with the Taliban is driven by two factors. First, national interest based on a pragmatic need to negotiate with the militant group to ensure stability in the region, while hedging by holding back from according it legitimacy or recognition to shape Taliban’s strategic and even domestic behavior. Second, antagonistic or friendly attitudes towards the Taliban reified through the prism of relations with the United States. Third, the realization that if external actors do not reach agreement then the resolution of this crisis will be made impossible, and the perceived benefits of instability will outweigh the necessary costs of stability – regional “blood and treasure.”

For Russia, Taliban support for both Chechen independence and the IMU before 9/11 was a cause for concern, as it highlighted the Taliban’s ability to enable the destabilization of Central Asia, a region perceived in terms of vulnerability and “soft underbelly” in Russian strategic psychology. Securing the borders of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan is a key priority for Russia and all Central Asian states, as ongoing CSTO military exercises underscore. Russia’s presidential envoy for Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, argues that, in effect, the “Taliban 2.0” movement is more capable of holding negotiations with Russia than the outgoing Kabul’s “puppet” government: “If we compare the credibility of colleagues and partners, the Taliban have long seemed to me a much more credible partner for negotiations than the puppet Kabul government.” Russia’s Afghan envoy highlighted Russia’s “long established ties, contacts with the Taliban movement” and argued that “The fact that we prepared the ground in advance for dialogue with the new government in Afghanistan is an asset of the Russian foreign policy, which we use fully in the long-term interests of the Russian Federation.70 Indeed, Russia has actively negotiated with the Taliban in Moscow, most recently on July 8–9, 2021, when the Taliban representatives asked Russian authorities to remove the militant group from the UN Security Council’s sanctions list. On August 20 President Putin called on the international community to end to what he called further attempts to impose “alien values” on other states and given the Taliban had taken de facto control of Afghanistan, this “needs to be accepted as such, avoiding the destruction of the Afghan state.”71 As in China, in Russia there is a suggestion in its strategic community that the U.S. only withdrew once its strategic goal – “manageable chaos” – could be implemented without their presence, to the determinant of Russian interests.

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi publicly met with Mullah Barader, the head of the Taliban political committee, in July 2021. As a result, the Taliban promises not to allow infiltration of extremism into Xinjiang, and in response China offers economic support and investment. China currently respects the “will and choice” of the Afghan people, has pledge to support Afghanistan’s reconstruction under a Taliban-led regime, but has yet to officially recognised the Taliban as the country’s legitimate government. Chinese state media and analysts express uncertainty over the Taliban’s pledges to cut ties with the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM). ETIM used Afghanistan’s territory between 1996-2001 to conduct training, establish camps and instigate terrorist attacks and violence in Xinjiang and Chinese analysts note that the Taliban is obliged by its fundamentalist ideology to provide a safe haven for Islamist groups. At best Taliban may prevent ETIM from engaging in anti-Chinese operation from Afghan territory, but unlikely to hand over ETIM fighters to China. China also wants to safeguard its trade arteries in the region from disruptive and destabilizing threats and secure its strategic economic assets in Afghanistan, namely, the Belt and Road Initiative, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and its copper, oil and lithium concessions in Afghanistan itself. If Afghanistan stable, the world’s rare earth lithium market will be more than ever the monopoly of China.72 China is concerned that the U.S. could indirectly sabotage China’s interests in the country by destabilising China’s investment projects in Afghanistan through “controllable unrest” to contain China.73

Pakistan’s Ambassador to Afghanistan Mansoor Ahmad Khan confirms that Islamabad was in contact with the Afghan Taliban: “Our special envoy was in contact with them in Qatar, and Mullah Baradar and other leaders of the Taliban held talks with us there. We had also spoken to the Afghan delegation, which Abdullah Abdullah was leading.” Khan said he was “in contact with both sides,” noting that Pakistan wished to see an inclusive political settlement in Afghanistan so ensuring sustainable peace in the region.74 Although Pakistan states that it will only recognize the Taliban “according to international consensus,” remarks by Prime Minister Imran Khan to the effect that Afghan nationals have “broken the shackles of slavery” and that the Taliban are “not a military outfit” but rather “normal civilians” suggest Pakistan wants to legitimize a Taliban-led government in Afghanistan. Of all the neighbors, Pakistan is the closest ethnically (Pashtun), militarily and ideologically, and has the greatest influence.75

The Taliban’s anti-Shiism is a concern for the Islamic Republic of Iran, which fears being drawn into a long war with the extremist Sunni “Islamic Emirate” and its extremist affiliates, which can directly attack the Shia Hazara minority in Afghanistan. Iran and the Taliban came close to war in 1998, after eight Iranian diplomats and a journalist were killed following the Taliban takeover of Mazar-e Sharif. More than 1.5 million Afghan immigrants live in Iran and Iran creates refugee camps along its Afghan border in anticipation of an influx of refugees. Iran is also concerned about the possibility of an increase in the narcotics trade across its 572 mile border. However, Iran does embrace the narrative of “anti-American Victory” and Afghanistan’s “Islamic Emirate” appellation is welcomed. Iran’s new President Ebrahim Raisi, in talks with Iran’s outgoing foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, has said “the U.S. military defeat and withdrawal from Afghanistan” should offer an opportunity for lasting peace in the country. Iran supports Ex-President Hamid Karzai’s proposed plan on forming a power transition council.76 The hope in Tehran will be that Iranian-“Taliban 2.0” co-existence may be possible.

The prospects for Turkey are more promising as multiple opportunities exist to develop relations with Taliban regime and to position Turkey as mediator between Taliban and the West. However, Turkey’s relations are dependent on actions and policies of other regional actors, such as China, Russia, and Iran. Two domestic groups in Turkey have praised the Taliban’s take over, the Nationalist pro-China-Russia bloc, which hopes that the Taliban will work closely with China and Russia and Turkey joins this group; political Islamists and core AKP supporters, willing to use radical groups in Syrian conflicts and elsewhere.77 Islamist Kurdish Free Cause Party (Huda-Par) has welcomed the departure of foreign forces from Afghanistan. Patriotic Party’s chairman Dogu Perincek likened the Taliban to the Turkish Republic’s secular founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who launched the Turkish War of Independence. The party’s secretary-general Ozgur Bursa claimed that the Taliban’s victory “against U.S. imperialism... would unite Afghanistan.” This party often voices pro-Beijing and pro-Russian views and describes itself as anti-imperialist.78 President Erdogan’s narrative has stated “there is not much difference between him and Taliban understanding of Islam”79 and he confirms that Turkey is “open to cooperation.”80 Taliban’s spokeperson Suheyl Sahin stated that the Taliban will work with Turkey on several projects to reconstruct Afghanistan.81 Turkey’s attitude to Afghan military and security forces who have defected, its use of proxies in Afghanistan as well as the extent to which it counters Afghan’s opium production will all be indicators of the nature of Turkey-Taliban 2.0 relations.

The Indian government evacuated its diplomatic staff and has yet to publicly discuss its plans for engaging a Taliban governed Afghanistan. India appears to be the only neighbor that has not engaged the Taliban, whose potential support for Kashmir-based Islamist and reported closeness with rival Pakistan and anti-India militant groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Hizbul Mujahideen and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) is a cause for concern.82 India has been an active stakeholder in the reconstruction of Afghanistan, having invested U.S. $3 billion in developmental assistance on over 400 projects in all 34 provinces of Afghanistan since 9/11. For the moment, “It remains unclear how India will reconcile its relationship with the Taliban and salvage existing projects, including the already delayed Chabahar port construction. With the collapse of the civilian government in Afghanistan, will India again offer support to opponents of the Taliban, as it did with the Northern Alliance?”83

In addition, and critically for the United States, Western strategic failure on a peripheral interest allows regional strategic success and enables a U.S. (and Western) strategic reset of its foreign policy. While regional neighbors are incentivized to engage Afghanistan’s new regime following the sudden withdrawal of the West, two consequences follow. First, regional actors are compelled to expend their “blood and treasure” on Afghanistan to a common good, rather than elsewhere. Second, while immediate reputational damage is high, “Joe Biden’s decision on Afghanistan -- which is similar to the decisions of Barack Obama and Donald Trump -- is predictable. In fact, for better or for worse, the United States made a decision based on its own interests.”84 The withdrawal frees up the resources and attention of the political West to focus on long-term strategic challenges both domestic and foreign. On the domestic front, this includes: “poor public health, decaying infrastructure, rising inequality and economic insecurity, and a climate disaster that demands the full-scale transformation of the energy, transportation, and construction sectors.”85 In foreign affairs, the U.S. needs to rebalance diplomatic priorities and resources: “U.S. power thinly spread and limits Washington’s bandwidth for managing policy tradeoffs among regions.”86 The U.S. can “make the long overdue pivot from focusing on the Middle East to shoring up deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and Europe by improving its ability to prevail in large-scale combat against a great power.”87 Alongside advancing strategic competition with Russia and China in more favorable geographies and contexts, the DoD can also focus on counter-terrorism globally, and more attention can be given to COVID-19 and climate change. If such a reset is envisaged, it will be clearly reflected in the new U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) and then the National Defense Strategy (NDS), expected 2021-2022.

Conclusions

In considering the Taliban takeover, a key lesson is not to be found in premature assertions of weakening of U.S. global role and overall decline, but rather in the limits of an external actor’s ability to change a country from the outside without the support of the local population. Kabul fell to a perfect storm of inter-enabling proximate and structural causes, with a heavy dose of psychological factors and unanticipated second and third order effects to the fore.

By any measure, an initial costs/benefits calculus suggests strategic failure. It is however as yet “unproven,” to use a term in Scottish law, whether the “Taliban 2.0” is a more moderate iteration of its first incarnation. The degree to which the Taliban is more moderate or extreme will heavily shape if not determinate likely Taliban strategic behavior. It is unclear whether a more ideologically extreme Taliban government determined to create an “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” is more able to impose its will on the Afghan people but less inclined to address and interact with the outside world. Alternatively, a more moderate Taliban may have less ability to impose its will in Afghanistan, and certain factions may seek to advance global jihad. Conditions for the Afghan people are less severe, but threats to the neighbors and the West are greater. What is certain is that Taliban strategic behavior going forward will influence debates over the nature of “strategic failure,” the costs/benefits calculus, the threat-based approach, and strategic withdrawal, regional stabilization and U.S. reset approach.

As noted below, IS-K is more extreme than the Taliban. Founded in 2015, it consists of marginalized former Taliban commanders and extremist militants from Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Pakistan. IS-K claims responsibility for the August 26 Kabul Airport suicide attacks which killed at least 90 people, including 13 U.S. military personnel. IS-K labels this attack as a “martyrdom operation” against U.S. “occupiers,” disloyal “collaborators” (Afghans who helped the West) and lackey “apostates” (Taliban), making the killing of Taliban lawful under their interpretation of Islamic law. The murder is designed to tarnish the Taliban’s reputation, and undercut their recent political and territorial gains by highlighting the fragility of Taliban control and authority. IS, which lost its Caliphate, is determined through its IS-K affiliate to ensure that the Taliban does not gain an Islamic Emirate.

As with the threats-based assessment, it is too early to tell if regional partners will more effectively help stabilize Afghanistan. What can be asserted with certainty is that China, Russia, Iran, Pakistan and the Central Asian states are aware of the dangers of instability posed by the “contagion” that radical jihad ideology poses, as well as refugee spillovers and opium production and export. Each of the neighbors have direct stakes in an Afghanistan and shared spillover threats create an incentive and cooperative imperative for all. Russia fears the spread of unrest to the North Caucasus, as well as the demonstration power of a small but ideologically committed group seizing power in states with corrupt, ineffective and unpopular regimes. This has clear implications for Tajikistan and Russia’s 201st division. Iran understands that the Sunni Taliban is anti-Shia, but that IS-K more so, and so the Taliban the lesser evil. As China claims that terrorism has a material (under-development and inequality) not ideological base, there is every reason to invest in Afghanistan and maintain “effective communication and consultations” with the Taliban, especially given its repression of Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang acts as a magnet for radicalization. For Pakistan, to what extent does the fundamentalist, sharia law–focused Taliban in Afghanistan embolden the Taliban in Pakistan to overthrow the civilian elite?

After Russia and China’s de facto recognition of the Taliban on August 20, de jure recognition is likely to follow, in the hope that this external legitimacy will consolidate Taliban efforts to establish law, order and stability. The creation on August 25 of a 12-member council to lead Afghanistan includes the Taliban’s deputy political chief, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, Mullah Mohammad Yaqub, and senior member of the Haqqani Network, Khalil Rahman Haqqani. Russia’s ambassador to Kabul Dmitry Zhirnov stated that there is no alternative to the Taliban. The real text for regional actor cooperative efforts will be found after the final pull out from Kabul on August 31.

Will the U.S. reset its foreign policy around core national interest, and bring its friends and allies with it? Ultimately, how the potential U.S reset is structured will depend on how the U.S. strategic community, currently in flux with crisscrossing currents churning beneath the surface, view the Russia-China relationship, specifically: the “simultaneity” problem, that is potential actions by both that threaten U.S. vital interests; and the “distraction effect,” with its second mover advantage imperative incentivizing a second-front contingency. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan increases the Biden administrations bandwidth for managing policy tradeoffs, and in time, lessons identified may improve the functionality of its existing transatlantic and Asia-Pacific alliances. Will Washington look to “flip” Russia, the weaker member of the Russia-China axis, or undercut the weaker and accept delaying rivalry with the stronger (China) or attempt to coopt both? Afghanistan presents an interesting fourth option: to provide the incentive for both to cooperate for a common public good – the stabilization of Afghanistan. At the same time, engagement with a turbulent Afghanistan has the potential to exacerbate Russia’s latent fear of subordination, and expose the frictions and tensions inherent in the strategic behavior of transactional authoritarian actors, whatever the rhetoric from Russia lauding “strategic partnership” and China promising “win–win” outcomes as part of a common human destiny.

For Academic Citation

Graeme Herd, “The Causes and the Consequences of Strategic Failure in Afghanistan?” Marshall Center Security Insight, no. 68, August 2021,

https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/causes-and-consequences-strategic-failure-afghanistan-0.

Notes

1 Interview with Mohammad Haneef Atmar, Afghan Minister of Foreign Affairs, by Nataliya Portyakova; date and place not given, “This is not a civil war.” Izvestiya, in Russian, August 3, 2021.

2 Angela Giuffrida, “Expected Afghan Influx Reopens Divisions Over Refugees in Europe.”The Guardian, August 16, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/16/expected-afghan-influx-reopens-divisions-over-refugees-europe

3 Jonathan Landay, “Profits and poppies: Afghanistan’s illegal drug trade a boon for Taliban.” Reuters, August 16, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/profits-poppy-afghanistans-illegal-drug-trade-boon-taliban-2021-08-16/; “Opium: Afghanistan’s drug trade that helped fuel the Taliban.” Al Jazeera, August 16, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/8/16/opium-afghanistans-illicit-drug-trade-that-helped-fuel-taliban; Christopher Woody, “The U.S. totally failed to stop the drug trade in Afghanistan, but the Taliban found a better way to cash in.” Insider, August 17, 2021. https://www.businessinsider.com/afghanistan-us-couldnt-stop-drugs-but-taliban-profits-more-elsewhere-2021-8

4 Ali Anozla, “From “Khomeni’s Revolution” to Taliban Victory.” Al-Araby al-Jadeed, in Arabic, August 18, 2021. https://www.alaraby.co.uk/opinion

5 Peter Jennings, “Lessons from Afghanistan.” August 17, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/lessons-from-afghanistan/; Fawaz A. Gerges, “Terror and the Taliban.” August 17, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/will-the-taliban-give-al-qaeda-sanctuary-in-afghanistan-by-fawaz-a-gerges-2021-08

6 Gerges, “Terror and the Taliban.”

7 Brahama Chellaney, “Pax Americana Died in Kabul.” August 17, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/pax-americana-died-in-afghanistan-by-brahma-chellaney-2021-08

8 Mark Galeotti, “Moscow Watches Kabul’s Fall With Some Satisfaction, Much Concern.” Moscow Times, August 16, 2021. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/08/16/moscow-watches-kabuls-fall-with-some-satisfaction-much-concern-a74805

9 “Statement by President Joe Biden on Afghanistan.” August 14, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/14/statement-by-president-joe-biden-on-afghanistan/

10 Michael Shoebridge, “Was the Afghanistan withdrawal reckless or ruthless?” August 17, 2021. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/was-the-afghanistan-withdrawal-reckless-or-ruthless/

11 Melissa Jardine, “The world must evacuate women police in Afghanistan.” August 21, 2021. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/debate/afghanistan-after-america

12 France Hoang, “Don’t Fail America’s Allies.” WOTR, August 16, 2021: https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/dont-fail-americas-allies/

13 “It is time to try Ghani.” Hasht-e Sobh, Kabul, in Dari, August 15, 2021.

14 Mohammed Ayoob, “Afghanistan comes full circle.” August 17, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/afghanistan-comes-full-circle/With ImagesWithout Images

15 Charles A. Kupchan, “Biden Was Right.” August 16, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/biden-was-right-by-charles-a-kupchan-2021-08

16 Anatol Lieven, “An Afghan tragedy: the Pashtuns, the Taliban and the state.”

17 Daron Acemoglu, “Why Nation-Building Failed in Afghanistan.” August 20, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/afghanistan-top-down-state-building-failed-again-by-daron-acemoglu-2021-08

18 Jeffrey D. Sachs, “Blood in the Sand.” August 17, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/afghanistan-latest-debacle-of-us-foreign-policy-by-jeffrey-d-sachs-2021-08

19 Richard Haass, “America’s Withdrawal of Choice.” August 15, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/americas-withdrawal-of-choice-by-richard-haass-2021-08

20 Rodger Shanahan, “Afghanistan: the right time to leave.” August 16, 2021: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/afghanistan-right-time-leave See also: “The Taliban’s takeover of Kabul does not only mean the movement’s military victory over the Afghan army and security forces, on which the US and its allies spent billions in training, but it also means that the US political project in Afghanistan has been defeated.” “Al Jazeera notes ‘failure of US political project’ in Afghanistan.” BBC Monitoring. Al Jazeera TV, Doha, in Arabic, August 16, 2021.

21 Richard Haass, “America’s Withdrawal of Choice.” August 15, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/americas-withdrawal-of-choice-by-richard-haass-2021-08; Elio Gaspari, “Kabul, Saigon, Shaaban, Budapest.” Folha de Sao Paulo website (www.folha.com.br), Sao Paulo, in Portuguese, August 17, 2021.

22 Andrei Yashlavsky, “Everything collapsed at lightning speed in Afghanistan: a lesson for Russia.” MK, August 16, 2021. https://www.mk.ru/politics/2021/08/16/v-afganistane-vse-rukhnulo-molnienosno-urok-dlya-rossii.html

23 I am grateful to Dr. Karen Finkenbinder for these observations.

24 “Afghanistan Takeover Sparks Concern From NATO Allies.” Deutsche Welle, August 16, 2021; Michael Rubin, “NATO Is Dead Man Walking After Afghanistan Debacle.” August 19, 2021. https://www.19fortyfive.com/2021/08/nato-is-dead-man-walking-after-afghanistan-debacle/

25 Matthew Karnitsching, “Disbelief and Betrayal: Europe Reacts to Biden’s Afghanistan ‘Miscalculation.’” Politico, August 17, 2021.

26 Liz Sly, “Afghanistan’s collapse Leaves Allies Questioning U.S. Resolve on Other Fronts.” Washington Post. August 15, 2021.

27 Helen Warrell, Guy Chazan and Richard Milne, “Nato allies urge rethink on alliance after Biden’s ‘unilateral’ Afghanistan exit.” Financial Times, August 17, 2021.

28 Mark Landler, “Biden Rattles U.K with his Afghan Policy,” New York Times, August 18, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/18/world/europe/britain-afghanistan-johnson-biden.html

29 Russian Security Council secretary Nikolai Patrushev in an interview with Alexei Zabrodin, “Supporters of US choice in Ukraine to face similar situation.” Izvestiya, in Russian, August 19, 2021. https://iz.ru/1209165/aleksei-zabrodin/pokhozhaia-situatciia-ozhidaet-i-storonnikov-amerikanskogo-vybora-na-ukraine

30 Peter Jennings, “Lessons from Afghanistan.” August 17, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/lessons-from-afghanistan/

31 “Chinese media celebrate fall of US ‘hegemony’ in Afghanistan.” BBC Monitoring. Multi-source write-up from Chinese sources, in Chinese (written), August 17,2021.

32 Ibid.

33 Michael Shoebridge, “Was the Afghanistan withdrawal reckless or ruthless?” August 17, 2021. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/was-the-afghanistan-withdrawal-reckless-or-ruthless/

34 Peter Jennings, “Lessons from Afghanistan.” August 17, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/lessons-from-afghanistan/

35 Yuriy Romanenko, “A sombre lesson for Ukraine.” Glavred, August 15, 2021. https://opinions.glavred.info/mrachnyy-urok-dlya-ukrainy-pochemu-ssha-ne-paryatsya-iz-za-afganistana-10295511.html; Nikolas K. Gvosdev, “Afghanistan Is a Wake-Up Call for ‘Major Non-NATO Allies,’ ” The National Interest, August 14, 2021: https://nationalinterest.org/feature/afghanistan-wake-call-%E2%80%98major-non-nato-allies%E2%80%99-191864

36 “US ‘chaotic exit’ from Afghanistan ‘sobering reminder to S Korea,” Yonhap news agency, in English, August 18, 2021.

37 Lahav Harkov, “Netanyahu rejected Kerry’s Afghanistan-style solution for Palestinians.” The Jerusalem Post, August 18, 2021. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/netanyahu-rejected-kerrys-afghanistan-style-solution-for-palestinians-677046

38 Jamal Zakhalka, “Redoing calculations after the American escape,” Al-Quds al-Arabi, August 19, 2021.

39 “Highlights from Pakistan’s Urdu-language press,” websites, August 16, 2021. BBC Monitoring, Roundup, August 16, 2021.

40 “Afghan Taliban urge ‘friendly relations’ with all countries,” BBC Monitoring - Ariana News website, Kabul, in English, August 19, 2021.

41 Yasser Abu Hilala, “The Attraction of the Taliban May be Useful,” Al-Arabi al-Jadid, in Arabic, August 19, 2021.

42 “Afghan Taliban military chief orders members to respect private property,” BBC Monitoring, Tolo News, Kabul, in Dari, August 17, 2021.

43 “Fears of life under the Taliban,” Eslah, Kabul, in Dari, 10 August 2021.

44 Stefano Stefanini, “Trust Is Obligatory, Let’s Not Sell It Off Cheap.” La Stampa website, in Italian, August 18, 2021.

45 Anastasia Kapetas, “After the fall of Kabul, what’s next for Afghanistan?” August 15, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/after-the-fall-of-kabul-whats-next-for-afghanistan/

46 “Afghan TV reports Massouds call for anti-Taliban resistance.” BBC Monitoring. Afghan TV channels, in Dari and Pashto, August 19, 2021.

47 “Europe Urges Unity on Taliban, is Quiet on Failed Mission.” VOA, August 16, 2021. https://www.voanews.com/south-central-asia/europe-urges-unity-taliban-quiet-failed-mission

48 “Afghan politicians form three-member ‘coordination council,” BBC Monitoring. Afghan Islamic Press news agency, Peshawar, in Pashto, August 15, 2021.

49 I am grateful for Dr. Tova Norlen, GCMC Faculty, for this observation.

50 “Al-Arabiya TV highlights Afghan women’s fate as Taliban take power.” BBC Monitoring. Al Arabiya TV, Dubai, in Arabic, August 16, 2021.

51 Daniel Byman, “Will Afghanistan Become a Terrorist Safe Haven Again?” August 18, 2021. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2021-08-18/afghanistan-become-terrorist-safe-haven-again-taliban

52 Fawaz A. Gerges, “Terror and the Taliban.” August 17, 2021: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/will-the-taliban-give-al-qaeda-sanctuary-in-afghanistan-by-fawaz-a-gerges-2021-08

53 “Al-Qaeda in Yemen congratulates Taliban on ‘victory.’ ” BBC Monitoring - RocketChat messaging service, in Arabic, August 18, 2021.

54 “Afghanistan: West African media see cautionary tale for Sahel forces.” BBC Monitoring - African sources in French and English, August 18, 2021.

55 Anastasia Kapetas, “After the fall of Kabul, what’s next for Afghanistan?” August 15, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/after-the-fall-of-kabul-whats-next-for-afghanistan/

56 “Secretary Antony J. Blinken With Chuck Todd of Meet the Press on NBC.” Interview. Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, Washington, D.C. August 15, 2021: https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-with-chuck-todd-of-meet-the-press-on-nbc/

57 Kabir Taneja and Mohammed Sinan Siyech, “Terrorism in South Asia After the Fall of Afghanistan,” August 23, 2021: https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/terrorism-in-south-asia-after-the-fall-of-afghanistan/

58 For speculation regarding its impact on the Balkans, see: Mirjana Cekerevac, “Afghanistan Crisis To Affect Serbia and the Region,” Politika website, in Serbian, August 17, 2021; Danijjal Hadzovic, “Afghan Lesson for Bosnia and Hercegovina,” Dnevni avaz website, in Bosnian, August 18, 2021.

59 Anastasia Kapetas, “After the fall of Kabul, what’s next for Afghanistan?” August 15, 2021: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/after-the-fall-of-kabul-whats-next-for-afghanistan/

60 “This is the victory of the entire Islamic Ummah [Muslim community]. The future of the Islamic Ummah depends on it. The TTP renews its allegiance to the Islamic Emirate, and pledges not to hesitate in making any sacrifice for the stability and development of the Islamic Emirate in the future, and we consider it our Islamic and Sharia responsibility.” “Pakistani Taliban chief ‘renews’ allegiance to Afghan Taliban,” BBC Monitoring - Afghan Islamic Press news agency, Peshawar, in Pashto, August 17, 2021.

61 Aaron Boxerman and AFP, “Hezbollah chief: Israel should learn from Afghanistan that US is unreliable.” The Times of Israel, August 18, 2021. https://www.timesofisrael.com/hezbollah-head-israel-should-learn-from-afghanistan-that-us-is-unreliable/?fbclid=IwAR1V31LXei6Fy3SdAsE2vLH24MBP1rxIWdzqXYu8rLuOJEXiVnEd2u1gYa0 I am grateful to Tamir Sinai for drawing my attention to this point.

62 Aaron Boxermann, “Hamas praises Taliban for causing American ‘downfall’ in Afghanistan.” The Times of Israel, August 16, 2021. https://www.timesofisrael.com/hamas-praises-taliban-for-causing-american-downfall-in-afghanistan/

63 “Syria jihadist group HTS congratulates Taliban for ‘great victory,’ ” BBC Monitoring - Telegram messaging service, in Arabic, August 18, 2021.

64 “Afghanistan: West African media see cautionary tale for Sahel forces.” BBC Monitoring - African sources in French and English, August 18, 2021.

65 “Burkina Faso paper says Afghan crisis warning to Sahel,” Le Pays, Ouagadougou, in French, August 17, 2021.

66 Sahel: “Les groupes jihadistes n’ont pas les mêmes capacités ni trajectoires ici qu’en Afghanistan.” Radio France Internationale website, Paris, in French, August 19, 2021. https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/invit%C3%A9-afrique/20210819-sahel-les-groupes-jihadistes-n-ont-pas-les-m%C3%AAmes-capacit%C3%A9s-ni-trajectoires-ici-qu-en-afghanistan

67 Bill Emmott, “The Real Failure Is Pakistan.” August 18, 2021. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/pakistan-is-real-cause-of-failure-in-afghanistan-by-bill-emmott-2021-08

68 Andrew E. Kramer and Anton Troianovski, “With Afghan Collapse, Moscow Takes Charge in Central Asia.” New York Times, August 19, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/19/world/asia/afghanistan-russia.html

69 “Difficulties linked with the pandemic, economic hardships, unemployment and other social problems could now be viewed through the prism of ‘instability’ in Afghanistan, a genocidal war. As a result, discomfort and stress in society may reach certain stability. This situation will also affect the upcoming presidential election as a strong psychological factor. That is, when there is a big trouble in a neighboring country, the degree of consolidation of Uzbek society around the government will increase.” BBC Monitoring - “Highlights from Central Asian press,” websites, August 16, 2021.

70 “Russian envoy says Taliban easier to negotiate with than ‘puppet’ government,” BBC Monitoring, Russian sources in Russian, August 16, 2021.

71 “Putin urges West top stop imposing ‘alien values’ after Afghan exit,” BBC Monitoring, Rossiya 24 news channel, Moscow, in Russian, August 2021.

72 I am grateful to Dr. Pál Dunay, GCMC faculty, for this observation through e-mail exchange.

73 “Chinese media, experts assess risks to Beijing’s investments in Afghanistan,” BBC Monitoring - Multi-source write-up from Chinese sources in Chinese (written), August 19, 2021.

74 “Pakistan says in contact with Afghan Taliban.” The News website, Islamabad, August 20, 2021. BBC Monitoring, August 20, 2021.

75 Yasser Abu Hilala, “The Attraction of the Taliban May be Useful,” Al-Arabi al-Jadid, in Arabic, August 19, 2021.

76 “Iran president says US ‘defeat’ in Afghanistan opportunity for lasting peace.” BBC Monitoring. president.ir website, Tehran, in Persian, 16 August 2021.

77 E-mail exchange with Dr. Cüneyt Gürer, GCMC Faculty, August 18 and 20, 2021. My thanks to Dr. Gürer.

78 “Pro-Taliban voices in Turkey praise group’s ‘victory’ in Afghanistan,” BBC Monitoring - Turkish sources, August 19, 2021.

79 “Erdoğan says Taliban can comfortably negotiate with Turkey as ‘We have nothing against their beliefs.’ ” BIA News Desk, July 21, 2021. https://m.bianet.org/english/world/247494-erdogan-says-taliban-can-comfortably-negotiate-with-turkey-as-we-have-nothing-against-their-beliefs

80 “Turkey’s autocratic leader praises the Taliban’s ‘moderate statements’ and says he’s ‘open to cooperation.’ ” Insider, August 18, 2021. https://www.businessinsider.com/turkey-erdogan-says-hes-open-to-cooperation-with-taliban-2021-8

81 “Taliban Spokesperson Suheyl Şahin: We need Turkey more than anyone else.” (Original article in Turkish “Taliban Sözcüsü Suheyl Şahin: Herkesten çok Türkiye'ye ihtiyacımız var.” Sputnik Turkey. August 20, 2021. https://tr.sputniknews.com/20210820/taliban-sozcusu-suheyl-sahin-herkesten-cok-turkiyeye-ihtiyacimiz-var-1048181320.html

82 Sumaiya Ali and Sachin Gogoi, “Analysis: Isolated India calibrates approach to deal with Afghan Taliban,” BBC Monitoring, Insight, August 20, 2021.

83 Stuti Bhatnagar, “Afghanistan’s collapse shifts strategic dynamics in South Asia.” August 18, 2021. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/afghanistan-s-collapse-shift-strategic-dynamics-south-asia

84 Gianpiero Massolo, “Italy, Europe, and Realpolitik.” La Stampa website, in Italian, August 18, 2021.

85 James K. Galbraith, “Afghanistan Was Always About American Politics.” August 20, 2021. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/afghan-war-was-about-us-politics-by-james-k-galbraith-2021-08

86Wess Mitchell, “A Strategy for Avoiding Two-Front War.” WOTR, August 23, 2021. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/strategy-avoiding-two-front-war-192137?page=0%2C3; Korwin-Mikke, “A Two Foes Policy,” Rzeczpospolita, Warsaw, in Polish, August 19, 2021.

87 Stacie L. Pettyjohn and Becca Wasser, “From Forever Wars to Great-Power Wars: Lessons Learned From Operation Inherent Resolve.” WOTR, August 20, 2021. https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/from-forever-wars-to-great-power-wars-lessons-learned-from-operation-inherent-resolve/

About the Author

Dr. Graeme P. Herd is a Professor of Transnational Security Studies and chair of the Research and Policy Analysis Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (GCMC). From January 2021, Dr. Herd directs a new GCMC Russia Hybrid monthly Seminar Series which focuses on Russian risk calculus, red lines and crisis behavior and the implications of this for policy responses for the United States, Germany, friends and allies.

Before joining the GCMC, Graeme was appointed Professor of International Relations and founding Director of the School of Government, and Associate Dean, Faculty of Business, University of Plymouth, UK (2013-14). He established the ‘Centre for Seapower and Strategy’ at the Britannia Royal Naval Academy, Dartmouth. He has an MA in History-Classical Studies from the University of Aberdeen (1989), and a PhD in Russian history, University of Aberdeen (1995).

Graeme has published ten books, written over 70 academic papers and delivered over 100 academic and policy-related presentations in 46 countries. He is currently writing a manuscript that examines the relationship between Russia’s strategic culture and President Putin’s operational code on decision-making in Russia today.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies