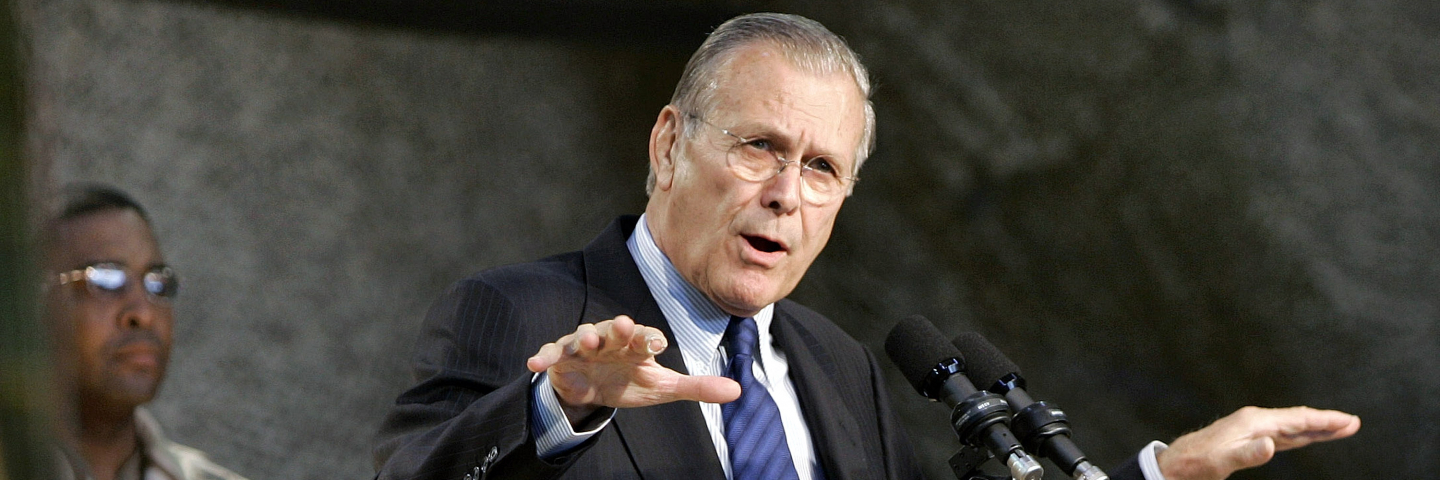

Business as Usual: An Assessment of Donald Rumsfeld’s Transformation Vision and Transformation’s Prospects for the Future

Donald Rumsfeld’s vision of a transformed United States military has been discussed by many and understood by few. It is no surprise that this lack of understanding has resulted in both significant simplifications and sweeping generalizations, to include the Reuters headline noted above. Even the term, “Rumsfeld’s Transformation,” accounts for neither the historical influences that led to his vision, nor the multiple components of this transformational effort.

Donald Rumsfeld did not invent Transformation. Nor was he the sole source of goals to build a high- technology, information-enabled joint military. Soviet military theorists have discussed “Military- Technical Revolutions” since the early 1970s. The conceptual basis for what the Bush Administration hoped to achieve with Transformation is the 1996 publication, Joint Vision 2010, a Clinton-era document. However, the facts are that Rumsfeld made Transformation a singular priority and that he pursued the effort with noteworthy zeal. But by 2007, defense language shifted from “transforming” to “recapitalizing” the military. Rumsfeld was out of office and the organizations he created to facilitate Transformation were reabsorbed by the larger Pentagon bureaucracy.3

If Rumsfeld’s Transformation is indeed dead, does this mean that Transformation as a greater process is dead as well? Answers to such questions require one to understand first that “Rumsfeld’s Transformation Vision” is actually the result of multiple influences that predate his time in office. Second, “Rumsfeld’s Transformation Vision” is actually an umbrella term for three different things: a new way of war, a process, and a defense strategy. And third, in spite of Rumsfeld’s reputation for aggressive leadership, the military services shaped, and at times limited, the effectiveness of his program.

Generic Transformation

In its purest sense, Transformation is neither an end state, nor a modernization program, nor a rapid advancement in technology. Rather, Transformation is a process, rooted in a deliberate policy choice, which involves changes in military organizations, cultures, doctrine, training, tactics, and equipment. Transformation is enabled by a Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) and in response to a significant change in a nation’s security context.4 Without both the opportunity created by RMA and the challenge presented by changes in the security context, a government’s decision to transform its military is either impossible or pointless.

For the United States, and arguably the world, the current RMA includes a myriad of technological improvements, to include advancements in computers, communications, space technologies, and to some degree, manufacturing. These technological improvements manifested themselves with US dominance in stealth technology, precision strike, maneuver (both strategic and tactical), and targeting. The American strategic context reflects its position as the world’s only superpower as the Cold War ended as well as the emergence of a more volatile, complex, and uncertain world characterized by surprise.5

Literature Review

Rumsfeld was not alone in his understanding that a revolution in military affairs was in progress and that the strategic context had changed for the United States. As there is extensive academic and governmental literature on the subject of American Military Transformation, the following discussion highlights only a few of the most significant works on the subject and is hardly exhaustive.

As can be expected with efforts like Rumsfeld’s push for US military transformation, the US Department of Defense and the military services were prolific in their production of literature on the subject. The value of each piece varies depending upon its intended audience and intended use. Some pieces targeted the young soldier, seaman, marine, or airman and talked about their individual contributions to the effort. Others attempted to explain the process to departmental outsiders and decision-makers in Congress. Still others served as functional references for staff officers and agencies responsible for Transformation’s execution.

No analysis of American military transformation would be credible without reference to Joint Vision 2010 and Joint Vision 2020.6 These documents, produced in 1997 and 2000 respectively, outline the new way of war envisioned by the early corps of transformationalists. They highlight how military conflict would evolve given new technologies over the next 15 to 20 years. They were never intended as policy documents, but rather represented a reasonably coherent and succinct explanation of future military operations following the RMA and America’s new strategic context.

Likewise, the 2001 and 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review Reports7 are significant in understanding how the Defense Department perceived itself and its readiness vis-à-vis the American strategic context. These reports are congressionally mandated, with the first produced in 1997, and with the next due in 2009. The 2001 and 2006 versions are most useful, however, in understanding the Rumsfeld-era effort.

Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach is an excellent Rumsfeld-specific resource for understanding the reasons for transformation, its end state, and the broad management model used to achieve success.8 This publication is accompanied by “Elements of Defense Transformation,” although Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach is clearly more exhaustive and detailed.9 Particularly noteworthy are the discussions of the three-part scope of Rumsfeld’s transformation program, the leadership process he intended to apply, and what he saw as the emerging way of war. These publications also identify transformation’s four pillars, and six operational goals.

For a detailed discussion of the specific goals and tasks associated with Rumsfeld’s transformation process, the 2003 document, Transformation Planning Guidance, is critical.10 This document outlines specific organizational responsibilities, tasks, and timelines associated with the effort to include concept development, experimentation, and service-specific plans and products that reflect the core of transformation’s institutionalization.

For service-specific thought on transformation, the services’ different “Transformation Roadmaps” serve as important references. The Transformation Planning Guidance directed that each service produce these roadmaps annually, although production was limited to 2003 and 2004 only. These documents discuss how each service understands transformation, service priorities, and how each service views its joint interdependencies. For additional insight on service priorities and goals, one should consult each service’s annual posture statements, which are still in production.

Agencies outside the Department of Defense (DOD) add an important outsider’s view, and can often serve as quick primers on transformation. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) each produced a large number of studies on transformation, addressing a wide variety of DOD, combatant command, and service-level issues. The intended audience for most CBO and GAO publications is the US Congress. Therefore, these studies tend to be brief and succinct, but also tend to omit a lot of detail. As a result, DOD has at times disagreed with CBO and GAO assessments, citing a lack of understanding of how the department was operating, or that reports failed to address the whole picture.11

More thorough “outsider” reports can be found through the Defense Science Board (DSB). The DSB is a “Federal Advisory Committee established to provide independent advice to the Secretary of Defense.”12 A particularly noteworthy DSB series is the 2006 Defense Science Board Summer Study on Transformation: A Progress Assessment, Volumes 1 and 2. The first volume is a summary report, and therefore most useful. The second volume is a compilation of the multiple independent sub-studies that completed the overall study. Even though the DSB works for DOD, this series offered several frank and thoughtful insights into the successes and shortcomings of Rumsfeld’s transformation effort.

The list of institutions, both inside and outside the US government that devoted significant effort to discussing transformation is particularly long. Even though this list is not exhaustive, the following organizations produced several thought-provoking and scholarly pieces:

- National Defense University, Washington, D.C.

- Joint Forces Staff College, Norfolk, Virginia

- The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, Washington, D.C.

- The Council on Foreign Relations

- The RAND Corporation

- The US Military Services’ Staff Colleges and War Colleges

While there are many books devoted to the study of defense transformation, perhaps the two most complete and thorough texts are Max Boot’s War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History, 1500 to Today,13 and Frederick W. Kagan’s Finding the Target: The Transformation of American Military Policy.14 Boot’s lengthy book discusses over 500 years of revolutions in military affairs, to include the current information-based RMA. His linking of success to a nation’s bureaucratic efficiency is particularly unique and valuable when assessing the status of America’s current attempt at transformation.

Kagan’s history is much shorter, addressing only 50 or so years. Like Boot, Kagan acknowledges the current information-based RMA. However, Kagan is less enthusiastic than Boot about the prospects of this current RMA and even less so about its presumable support for airpower at the expense of ground forces. Kagan is especially doubtful about Network Centric Warfare, and concepts such as “Shock and Awe.” In the end, Kagan makes a strong case against the prospects for successful transformation in an era during which the US holds significant military dominance, and offers several compelling recommendations for the Pentagon.

Finally, each US military service has its key transformationalist thinkers, and their works would round out any library on military transformation. For the Army, it is Colonel Douglas A. Macgregor. Macgregor 1997 book, Breaking the Phalanx: A New Design for Landpower in the 21st Century, essentially laid the groundwork for the “Modular Army” and provided much of the theoretical basis for the service’s Stryker Brigade Combat Team as well as the Future Combat System.15 Macgregor’s more recent book, Transformation Under Fire: Revolutionizing How America Fights offers an Army- specific view of how land forces can and should prepare for a new age of joint expeditionary warfare.16 Although not written in response to Kagan’s Finding the Target, Macgregor’s enthusiasm for the prospects offered to land forces by the current RMA is a nice counter-balance to Kagan’s distaste for it.

The most noteworthy Air Force transformationalist is Colonel John Boyd. Boyd made the case for speed of command with his OODA loop in a series of slides entitled, “A Discourse on Winning and Losing.” OODA stands for “observe-orient-decide-and-act.” As the events of battle are played out, opposing forces, and even individual commanders, must go through the process of observing the events, orienting the events to the current situation, deciding what to do next, and then acting upon that decision. Boyd believed that victory would be enabled by the military capable of moving though this loop faster than its adversary.17 Transformationalists believe that the technologies of the Information Age, coupled with nimble forces will enable movement through the OODA cycle at increased rates.

Perhaps the most significant proponent for transformation is Naval Admiral Bill Owens. Owens coined the phrase, “system of systems” and is the author of Lifting the Fog of War.18 Owens argues that this information technology-enabled system-of -systems will accelerate a military’s ability to assess, direct, and act; thereby creating a “powerful synergy” and enable combat victory.19 Based upon this new synergy, Owens makes the theoretical case for much of Rumsfeld’s transformational effort to include unified command structures, enhanced jointness, embedded information warfare capabilities, leaner combat structures, and enhanced mobility.20

Transformation’s Heritage

“We need rapidly deployable, fully integrated joint forces capable of reaching distant theaters quickly and working with our air and sea forces to strike adversaries swiftly, successfully, and with devastating effect. We need improved intelligence, long-range precision strikes, sea-based platforms to help counter the access denial capabilities of adversaries.”21

Approximately one year into the Bush Administration, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld succinctly presented his oft-cited vision for transformation during a speech to the National Defense University at Fort McNair, Washington, DC. This vision did not occur in a vacuum. Rather, it has a lineage of influences pre-dating the Secretary’s time in office.

These influences include previous thought on what transformation meant, conservative opinions on how the Clinton Administration handled transformation, the state of the force Rumsfeld inherited, and perhaps most importantly, presidential direction. Rumsfeld’s subsequent approach reflected each of the above influences as well as Rumsfeld’s leadership style. It would be daunting by any objective standard. While transformation certainly included a significant modernization program, with proponents and detractors in its own right, it was much more. Understanding that transformation begins in the mind, Rumsfeld questioned organizational, doctrinal, personnel, and acquisition practices. Service- specific roles, responsibilities, and “truths” were on the table. It appeared that nothing would be sacred.

This chapter outlines the historical antecedents that led to Rumsfeld’s transformation approach. Highlights include its history, beginning with the close of the 1991 Gulf War and the intellectual base that evolved since the war’s end. In addition, it discusses perceptions and realities of the American military, particularly with regard to budgetary priorities and military culture under the Clinton Administration. It concludes with discussion of Rumsfeld’s three transformational targets.

Transformation’s Historic and Conceptual Roots

The notion of transformation formally entered the Pentagon’s lexicon around 1997, with the publication of Joint Vision 2010, which the department updated in 2000 as Joint Vision 2020. However, the notion of an upcoming Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) more accurately began after the 1991 Gulf War.22 Then Secretary of Defense, Richard Cheney commented in the official Department of Defense report on the conflict that “this war demonstrated dramatically the new possibilities of what has been called the ‘military-technological revolution in warfare.’”23 Over the following years, this perception gained popularity among the Pentagon’s intellectual sect, to include the Office of Net Assessment’s director, Andrew Marshall, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff Admiral William Owens, and even among experts outside the department.24 The view also gained a receptive audience in the defense manufacturing and analytical industries which feared a decline in military budgets following the Gulf War and the demise of the Soviet Union.25 Effectively arguing that the stakes were high, this dynamic and influential alliance made Transformation a departmental and congressional priority. Indeed, as US Army War College professor, Steven Metz notes, this group convinced key policymakers “that America’s security depended on mastering the ongoing RMA.”26 It is these intellectual and political events that set the stage for Joint Vision 2010’s production in 1997.

However, Joint Vision 2010 was, as its title suggests, simply a “conceptual framework.”27 By design, it did not outline specific policy and doctrinal options. Policymakers needed more concrete options and recommendations through which to apply resources. For that, they looked to the first Quadrennial Defense Review, published also in 1997. Emphasizing the “threat of coercion and large-scale cross- border aggression against US allies and friends in key regions by hostile states with significant military power”28 this report focused on Desert Storm-type scenarios, and was lean on new ideas. As a result, an unimpressed Congress, through the 1997 Defense Authorization Act, directed the Secretary of Defense to commission a high-level National Defense Panel to generate more creative proposals. The Panel’s recommendations for “a broad transformation of its military and national security structures, operational concepts and equipment,” firmly linked future defense activities to this RMA.29

However, if the Clinton Administration agreed with this view, it was only on the margins. To be certain, the 1997 through 2000 National Security Strategies clearly discussed the RMA. However, the discussions lacked depth. Steven Metz called the strategy, “reform packaged as revolution.”30 The Project for a New American Century, a conservative Washington think-tank, was notably more critical:

Yet for all its problems in carrying out today’s missions, the Pentagon has done almost nothing to prepare for a future that promises to be very different and potentially much more dangerous. It is now commonly understood that information and other new technologies—as well as widespread technological and weapons proliferation—are creating a dynamic that may threaten America’s ability to exercise its dominant military power. […] [T]he Defense department and the services have done little more than affix a “transformation” label to programs developed during the Cold War, while diverting effort and attention to a process of joint experimentation which restricts rather than encourages innovation.31

At its best, the Clinton strategy was, in its own words, “a carefully planned and focused modernization program.”32 To its detractors, however, it indicated a failure of strategic leadership by avoiding tough calls.33 The truth was probably somewhere in between. To be fair, the Clinton strategy was consistent with the tone of Joint Vision 2010/2020. None of the 1997-2000 National Security Strategies challenged traditional service roles and responsibilities, and they clearly did not question or prioritize long-standing, service-specific modernization programs. As suggested by the department’s research and development budget (Figure 1), it appeared that future Clintonian military strategies would not drive technological innovation, but respond to it. Perhaps even more confounding to the Strategies’ detractors, over a decade after Goldwater-Nichols, “jointness” still meant “coordination” vice “integration.” Such an approach was uninspiring and lethargic, and it proved itself unsatisfactory to the corps of transformation revolutionaries.

Figure 1: Research and Development Budget34

It was a widely held view that in the 1990s, the United States was in a historically unique, post-Cold War, “strategic pause.” Widely published conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer called it America’s “Unipolar Moment.”35 In other words, the United States was, as a result of the Soviet Union’s demise, the world’s only military superpower with no foreseeable peer, or even near-peer, state competitor in the close future. While most analysts agreed with this assertion, they differed on this pause’s by-product and opportunities.36 A common phrase in the 1990s was, “Peace Dividend.” Peace Dividend proponents argued that this period was an opportunity to reduce military expenditures, focus on domestic priorities and even balance federal budgets. Alternatively, American conservatives considered this an opportunity to bolster and transform the defense establishment, as well as focus on emerging asymmetric threats, such as weapons proliferation, enemy missile capabilities, and terrorism. Certainly to the defense manufacturing community, this opportunity included a chance to develop a new generation of weapons, thereby keeping defense budgets strong through the upcoming decades.

State of the Budget

One indicator of how the Clinton Administration viewed the strategic pause is its defense spending. And to the conservative establishment’s ire, the Clinton Administration pursued the “Peace Dividend” model. In spite of conservative complaints that Clinton neglected the Defense Department, the trend toward reductions in real defense spending began in 1986, during the Reagan Presidency. The sharpest decline since 1986 was in 1991, while George H.W. Bush was President. Nonetheless, it is fair to note that, in constant 2007 dollars, defense budgets remained flat or declined throughout the first six years of the Clinton Administration (see Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 2: US Defense Spending, FY 86- FY 0137

Figure 3: Defense Spending as a Percentage of the Federal Budget38

Figure 4: Percentage of Real Budgetary Growth by Service39

State of the Force

By 2000, modernization was not the only argument for increasing defense outlays in the new century. Indeed, modernization alone would not result in the new force envisioned by transformation proponents. The state of the force needed attention. Here, the discussion highlights issues of military culture, retention, and compensation.40 Popular and academic discussions of the time are fraught with observations on the paradox of simultaneous reductions in expenditures and infrastructure with increases in deployments and other operations. And there are no shortages of stories or “e-rumors” of soldiers’ families on food stamps. While it is true that these issues were not a simple as they seemed, nor were all of them trustworthy, it is worthwhile to note some significant, legitimate trends.

In February 2000, the Center for Strategic and International Studies published a comprehensive, academically rigorous and nonpartisan study on military culture in 1998 through 1999.41 While it is unclear to what degree policymakers referenced this specific study, it does highlight readily available trend data that would be worrisome to any incoming Defense Secretary, especially one looking to harness the opportunities of the ongoing RMA. Among such findings are the following:

- “Morale and readiness are suffering from force reductions, high operating tempo, and resource constraints.”42

- “Present leader development and promotion systems are not up to the task of consistently identifying and advancing highly competent leaders.”

- “Operations other than war, although essential to the national interest, are affecting combat readiness and causing uncertainty about the essential combat focus of our military forces.”

- “Although the quality and efficiency of joint operations have improved during the 1990s, harmonization among the services needs improvement.”

- “Reasonable quality-of-life expectations of service members and their families are not being met. The military as an institution has not adjusted adequately to the needs of a force with a higher number of married people.”43

Military operations in Somalia, Rwanda, Haiti, the Balkans, among many others, as well as the ongoing military presence in the Middle East were taking their tolls. Military members grew increasingly concerned about training and readiness quality. And perhaps most distressing to CSIS, “the services [were] losing a disproportionate number of their most talented service members.”44 It was clear that the very talent needed to lead this transformational effort was leaving the military for high-paying civilian jobs that offered increased familial stability.

Presidential Influence

Our military is without peer, but it is not without problems.

Former President George W. Bush (September 23, 1999)45

The challenges of average military member, the state of the Defense Department and its budget, and the conservative call for a transformed military hit a chord with Presidential Candidate George W. Bush. While the state of the military was not the preeminent issue upon which he campaigned, he advertised a vision for the military that addressed all the situations and challenges outlined thus far. Bush’s September 23, 1999 Citadel speech, “A Period of Consequences,” offers a plan that surely won approval of the transformationist corps. In this speech, he addressed every topic from current budgetary shortfalls, to the need for increased Research and Development budgets. He highlighted inadequate military pay and the services’ ongoing “brain drain.” He promised new application of the strategic pause and a transformed military:

My goal is to take advantage of a tremendous opportunity – given few nations in history – to extend the current peace into the far realm of the future. A chance to project America’s peaceful influence, not just across the world, but across the years.

This opportunity is created by a revolution in the technology of war. Power is increasingly defined, not by mass or size, but by mobility and swiftness. Influence is measured in information, safety is gained in stealth, and force is projected on the long arc of precision-guided weapons. This revolution perfectly matches the strengths of our country – the skill of our people and the superiority of our technology. The best way to keep the peace is to redefine war on our terms.

[…] The last seven years have been wasted in inertia and idle talk. Now we must shape the future with new concepts, new strategies, new resolve. […]

[I will] use this window of opportunity to skip a generation of technology. This will require spending more – and spending more wisely. […] I will expect the military’s budget priorities to match our strategic vision – not the particular visions of the services, but a joint vision for change.46

As is well known, George W. Bush did not win in 2000 with a mandate in the traditional sense. Nonetheless, history seemed to be working in the transformationists’ favor. The next challenge was to appoint a Secretary of Defense up to the task.

Enter Donald Rumsfeld

President Bush understood that the task would be immense.47 He needed someone with organizational creativity, experience in the Pentagon as well as with Congress, and conservative credentials to boot. Donald H. Rumsfeld would be that man. He had exactly the right pedigree: previous experience as the Defense Secretary, an impressive private sector career with the pharmaceutical corporation, Searle, and experience as a member of the House of Representatives. While Rumsfeld may have had some shortcomings, being a faithful lieutenant to his President was not one of them. Every indication of his approach to transformation reflects first, the President’s campaign promises; second, the clear desire to correct perceived shortcomings from the Clinton Era; and third, the circumstances that evolved since Desert Storm’s close in 1991. As one examines Rumsfeld’s approach to transformation, three distinct parts emerge. Rumsfeld approached transformation as a process, a new way of war, and a strategy.

A Process, a New Way of War, and a Strategy

Of the official transformation products, and as suggested by its title, Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach, is probably the most comprehensive strategic discussion. Through the text’s glossy pages, the Department of Defense broadly outlined Rumsfeld’s three-part approach to defense transformation. The Executive Summary opens with the Department’s official process-focused definition:

A process that shapes the changing nature of military competition and cooperation through new combinations of concepts, capabilities, people, and organizations….48

Continuing, the Executive Summary broadly describes the new way of war to be realized by this process:

Constructed around the fundamental tenets of network-centric warfare and emphasizing high-quality shared awareness, dispersed forces, speed of command, and flexibility in planning and execution, the emerging way of war will result in US forces conducting powerful effects-based operations to achieve strategic, operational, and tactical objectives across the full range of military operations.49

Toward the end of the Executive Summary, Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach offers the third part of Rumsfeld’s approach:

Transformation is [about] yielding new sources of power.50

Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach provides little depth to this part, but it is important nonetheless. Rumsfeld viewed transformation as a strategy unto itself. Terry Pudas, former Director of the Office of Force Transformation, described this as “a conscious effort to choose your future competitive space.”51 In short, Rumsfeld sought to change not only the American, but also the world’s approach to conflict. By accelerating the RMA’s opportunities, and perhaps even molding them, transformation would provide potential adversaries with an expensive security dilemma via new technologies, organizations and doctrine. And in turn, the strategy would arguably force potential aggressors to abandon their use even before seeking them.

As noted by President Bush in his Citadel speech, there existed a broadly held perspective that the Department’s and the services’ cultures were hindrances to significant change. The Pentagon itself needed to be fixed. Service traditions and independence hindered the military’s movement toward true jointness. Continuously focused inward, the Department of Defense failed repeatedly to leverage and employ capabilities available in other Executive Branch agencies. The Department’s bureaucracy, and to a similar degree, the services’ organizations, were bloated, cumbersome, constrained and unimaginative. Process outweighed product. These complaints were nothing new in defense circles.52 What is new is that Rumsfeld’s process addressed these complaints by identifying three targets in order to affect the cultural change: departmental business practices, interagency and coalition operations, and how the military fights.53 And it would be through these changes that the culture of flexibility and innovation required for transformation’s success would be realized. The target, “business practices,” refers to attempts to convert the department’s bulky and process-focused bureaucracy into a more responsive and innovative corporate structure. This structure includes human resource management and promotion schemes, acquisition and fiscal strategies, and operational planning and doctrine development cycles. The result would be an “altered risk-reward system that encourages innovation.”54 Concrete objectives included a new civilian personnel management process, called the National Security Personnel System (NSPS), and acquisition and budgeting programs that attempted to streamline the Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution (PPBE) System.55 This portion of the strategy sought to remedy the “State of the Force” problems identified earlier—and reverse the department’s “brain drain” by rewarding innovation and risk-taking.

“Interagency and coalition operations” refers to attempts to leverage capabilities already extant in other Executive Branch organizations and nations’ militaries to achieve what Joint Vision 2020 calls “Full Spectrum Dominance.” Rumsfeld sought to rebalance the nation’s interagency approach away from the military source of power. As the Office of Force Transformation observed:

Transforming the way the department integrates military power … with other elements of national power and with foreign partners will also help ensure that, when we employ military power, we do so consistent with the new strategic context. […] Political-military conflict … [cannot be resolved] by military means alone.56

This objective acknowledges the growing perception among American conservatives that the Clinton Administration too often sought military solutions, in a suboptimal way—and to the military’s detriment. The Center for Strategic and International Studies noted this concern in its military culture study. In his memoirs, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Colin Powell, offers a similar anecdote:

My constant, unwelcome message at all the meetings on Bosnia was simply that we should not commit military forces until we had a clear political objective. The debate exploded at one session when Madeline Albright, our ambassador to the UN, asked me in frustration, “What’s the point of having this superb military that you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?” I thought I would have an aneurysm.57

The fact that Albright eventually became Clinton’s Secretary of State, and that Powell became Bush’s Secretary of State makes this story especially illustrative as to the different visions between the Clinton Administration and the Bush Administration.

The final target is “how the military fights.” For several reasons, this received the preponderance of attention, particularly from the services. First, this would the forum for a potential roles and missions debate. Second, it would examine how the services execute their “organize, train, and equip” functions, thereby introducing the greatest potential to impact their budgets. And finally, it represented the portion of transformation that the department could largely execute with minimal external assistance or coordination. It would not necessarily involve personnel hiring, retention, and compensation schemes, so union and public relations issues were less of a factor, as in “business practices” target. And it involves less inter-departmental or international coordination as in the case of “interagency and coalition” operations. In short, this target was almost entirely within the purview of the Pentagon itself.

Transforming How America Fights

Rumsfeld faced three, sometimes conflicting, challenges. First, he had to execute the Global War on Terror. Second, he needed to buttress perceived budgetary and infrastructure shortfalls in critical components of the military force he inherited. And finally, he needed to fulfill a presidential promise to transform the military and with it, indoctrinate the Pentagon and services in new warfighting and organizational concepts.

This section offers additional insight into the processes associated with Rumsfeld’s approach to transformation. It discusses the leadership methods Rumsfeld applied and the organization he created as executive authority in order to make transformation a reality. Overall, reflecting not only his aggressive leadership style, but also the conservative perception that America was wasting the strategic pause’s opportunity, he chose the most intense methodology for action. The discussion continues with an explanation of the six “critical operational goals” and four “pillars” of transformation and how they relate to a new “capabilities-based” military.

Rumsfeld’s Process

Rumsfeld did not have the same luxury of time as his Clintonian predecessors—for three reasons. First, Rumsfeld needed to deliver on a Presidential promise with concrete, demonstrated action. Second, based upon prevalent conservative thought, he needed to leverage whatever was left of the strategic pause to produce a transformed military. And finally, the events of September 11, 2001 and interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq served only to intensify his sense of urgency.

Rumsfeld perceived three alternatives through which he could lead transformation. The first was via traditional modernization and recapitalization, as discussed in Clinton-era products like Joint Vision 2020 and the National Security Strategies of the late 1990s. Proponents of this steady modernization policy argued that the military would be transformed as a matter of continuous improvement.58 With new and updated technologies come new applications. Furthermore, this steady modernization policy increases expectations to blend these new technologies with enduring paradigms and principles, and in new ways, thereby expanding the military’s warfighting repertoire. In Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach, Rumsfeld termed this approach, “Continuous Small Steps.” The second approach is “A Series of Many Exploratory Medium Jumps.” Changes would be within the existing service paradigms, and highlighted intra-service organizational and doctrinal changes. Rumsfeld never dismissed these methodologies as non-transformational, but encouraged a third alternative: “Making a Few Big Jumps.” These jumps include measures “that will change a military service, the Department of Defense, or even the world.” The department would “explore things that are well away from core competencies.”59

At first blush, one could view this “Few Big Jumps” approach as recognition of the President’s 1999 promise to “skip a generation of weapons.” In reality however, the approach was more nuanced, and one aspect of the idea that transformation is a strategy. John Garstka, the Office of Force Transformation’s former deputy director, describes the approach as “creating a competitive advantage through an order- of-magnitude improvement.”60 Citing improvements gained through pre-Desert Storm technologies such as the Global Positioning System, night vision goggles, and stealth technology, Garstka explains that this approach represents attempts to apply the next generation of military technology to achieve similar advantages. Examples he cites as points for discussion include directed energy weapons, non- lethal weapons, and immediately responsive space systems. Alluding to the mathematical term for “order of magnitude” as a ten-fold change, he terms such big jumps, “Ten-X-ers.”61

The important consideration with pursuit of these “Ten-X” (or even less dramatic) improvements is the leadership demand required for success on behalf of the Defense Secretary himself. Under “Continuous Small Steps,” success can be achieved through strong management practices and standard bureaucratic processes. With the “Many Exploratory Medium Jumps” model, the leadership demand is placed primarily within each service. And with the “Few Big Jumps” approach, the Secretary would have to exercise strong, and at times, “bully pulpit” leadership (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparison of Transformational Approaches

Rumsfeld understood this leadership demand, and established a new organization to bolster his aggressive stance: the Office of Force Transformation (OFT). A think-tank of sorts, OFT would move transformation from the theoretical realm to the practical realm. With its director acting as the transformation czar, it would ensure that “joint concepts are open to challenge by a wide range of innovative alternative concepts and ideas.”62 The first OFT Director was retired Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski. Possessing extensive combat experience in Vietnam and Desert Storm, academic credentials as the former President of the Naval War College, and staff experience as the Joint Staff’s Director of Command, Control, Communications and Computers, Cebrowski offered the right blend of experience for the position. Furthermore, as demonstrated with his 1998 Proceedings article, “Network Centric Warfare: Its Origins and Future,” he was an early advocate of defense transformation.63 Within 30 days of his retirement from the U.S. Navy in October 2001, he began his new duties as the transformation czar.64

Even though OFT existed, Rumsfeld’s process leveraged the services’ traditional organize, train, and equip roles and US Joint Force’s (USJFCOM) enduring concept development role as transformation’s primary mechanism. Formal procedural direction came from the Transformation Planning Guidance (TPG). The TPG opens with a three-chapter discussion about the need for transformation’s and continues with a brief description of transformation’s scope and strategy, consistent with those outlined in Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach. For USJFCOM, the command’s responsibility focused on “developing joint warfighting requirements, conducting joint concept development and experimentation and developing specific joint concepts assigned by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.”65 The TPG further identified the Secretaries of the military departments and the services’ Chiefs of Staff as “responsible for developing specific concepts for supporting operations and core competencies … and build[ing] transformation roadmaps.”66

The TPG later specified that these roadmaps would be due to the Secretary not later than November 1 each year, with the initial product due in November 2003.67 And for content, the TPG insisted that these roadmaps be “actionable”:

The 2003 roadmap efforts [will] establish a baseline assessment across DOD’s transformation activities. The next set of revised roadmaps will address capabilities and associated metrics to address the six transformational goals and the joint operating concepts. In addition, the service roadmaps will provide a plan for building the capabilities necessary to support the [joint operating concepts]. Similarly, the joint roadmap will provide a plan for building joint capabilities in support of the [joint operating concepts].68

In summary, Rumsfeld’s process reflected an aggressive leadership model enabled by a transformation- specific organization and executed primarily through the services and US Joint Forces Command. The next challenge was to clarify what the process was working toward, but in actionable terms.

Rumsfeld versus “Joint Vision 2020”

Rumsfeld never identified Joint Vision 2020 as his benchmark for the transformed military,69 but a comparison of perceived new ways of war in the Clinton-era document with that described in several Rumsfeld-era documents illustrates that the differences were in terminology versus substance. One example is that Joint Vision applies Admiral Owens’ phrase, “system of systems” while Military Transformation emphasizes Cebrowski’s “Network Centric Warfare” concept. In the end, both envision rapidly deployable, highly dispersed forces executing precise, effects-based operations through shared awareness and speed of command.

Nonetheless, there are three important differences in nuance worth mentioning. The first is in reference to acquisition strategy as related to organization and warfighting constructs. The second is in the concept of jointness. The third difference is in how to develop a creative and innovative personnel culture. Joint Vision’s tone suggests that a “steady infusion” in widely available technology would enable the new warfighting capabilities, concepts, and structures suggested in the document.70 Alternatively, as shown in the Transformation Planning Guidance (TPG) of April 2003, Rumsfeld intended to invert this process:

Instead of building plans, operations, and doctrine around military systems as often occurred in the past, henceforth the Department will explicitly link acquisition strategy to future joint concepts in order to provide the capabilities necessary to execute future operations.71

As related to jointness, Joint Vision’s perception was less demanding than Rumsfeld’s vision. Although Joint Vision discusses “integration” and “interdependence,” and even makes room for “integration of the services’ core competencies,”72 its tone suggests that this would occur primarily at the Joint Force Commander level. Joint Vision’s emphasis clearly is on integrated decision-making and shared awareness with “synchronized” multi-component operations.73 Under Rumsfeld, “interdependence” would be the new standard. Reasons for this nuance are not immediately clear, but likely due to a desire to produce Joint Vision as a worthwhile product without pressing service sensitivities. The Air Force’s doctrinal stand that air forces must be commanded by an airman is one example of this sensitivity.74

The final nuance worth noting relates to Rumsfeld’s desire to target the Department’s and services’ “business practices,” and specifically, the way to create the innovative personnel force required for success. Joint Vision highlights the importance of joint training and education. Emphasis is on creating the personnel force of the future.75 There is no discussion of any aggressive effort to promote and retain the military’s and Pentagon’s most creative and adventurous members. As evidenced in the TPG, Rumsfeld flatly commented that the department represents it priorities, “most visibly by the promotion of individuals who lead the way in innovation.”76 The reason for this difference lies most likely with the Pentagon’s desire to produce Joint Vision as an enduring, and motivational, product by avoiding unique “brain drain” problems and concerns for job security.

Capabilities, Pillars and Goals

A capabilities-based force represents what the Pentagon will use to define future force structures; it represents transformation’s ultimate by-product. The 2001 QDR discusses the department’s shift away from a regional, two-war strategy to a new force structure that would be defined by skill sets that the services should possess. This shift necessarily requires the services (individually and as a team) to examine critically their enduring roles and responsibilities within the context of a fast-paced, asymmetric, information-enabled world. This absolutely does not say that traditional state-on-state war or enduring principles are now completely passé. However, the services do need to examine their skill sets with an eye toward their collective mission output across the spectrum of military operations. Force structure will then become a question not of “how many units, or tanks, ships, and planes,” but of “what type of effect, and how fast.” RAND Analyst, Paul K. Davis, in his essay, “Integrating Transformation Programs” offers a similar definition:

The first principle … is to organize … around mission capabilities. Although one can refer to aircraft, ships, and tanks as “capabilities,” the capabilities of most interest … are the capabilities to accomplish key missions. Having platforms, weapons, and infrastructure is not enough. Of most importance is whether the missions could be confidently accomplished in a wide range of operational circumstances.77

The capabilities-based force concept is further enabled by key supporting concepts. Most notable are Network Centric Warfare (NCW), and Effects Based Operations (EBO).

EBO has its supporters and detractors, and this project’s purpose is not to argue for or against its merits.78 It is, however, a key element to understanding the capabilities based force. US Joint Forces Command, in its glossary, notes that EBO “focuses upon the linkage of actions to effects to objectives.”79 Douglas Macgregor describes EBO a little more practically by noting that “effects- based thinking involves a logical process of identifying the [outcome] desired, and then building a cause-effect chain leading to the desired outcome.”80

EBO attempts to go beyond traditional force-on-force attrition warfare by accurately addressing the end-state desired. EBO understands that it is more important to change the enemy’s conduct than it is to destroy his forces. For example, if the Joint Forces Commander (JFC) wants to control an area, then the effect may be achieved by neutralizing the advancing enemy’s fuel supplies or eliminating routes through which he could enter the area with friendly long-range fires, air-power, or cruise missiles. The JFC could even use psychological or information operations to prevent the enemy force from considering the area as important. In all situations, EBO also requires the JFC to balance the military result with an understanding of secondary effects such as the local population’s perception of, and international support for, the operation.

Fred Kagan notes EBO’s popularity with airpower enthusiasts, and the Army’s reluctance to embrace it fully.81 But EBO does not, by itself, promote one service over another, nor does it make a singular case for smaller, lighter, or leaner forces. What EBO does promote is an understanding that effects are in the mind of the adversary, and that the long-term effects are as important as the short-term outcomes. Therefore, success demands an understanding of how the enemy sees and understands the events before him—and as such, requires a robust intelligence capability.

Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach argues that successful Effects Based Operations are impossible without network centric organizations. As noted in the same text,

NCW is not just dependent on technology per se; it is also a function of behavior. […] Power tends to come from information, access, and speed. NCW will capitalize on capabilities for greater collaboration and coordination in real time, the results of which are greater speed of command, greater self-synchronization, and greater precision of desired effects.82

In all, NCW emphasizes flatter command structures and lower level decision making, based upon a continuous awareness of commander intent and possible changes thereof. Terry Pudas links NCW to the idea that high speed, self-synchronizing information would “replace massed forces” in the modern battle-space.83 In other words, light, nimble forces enabled with information would be able to react faster than their adversaries to battle-space dynamics, thereby focusing effects upon the enemy in order to shape the outcome in a positive way, even though the enemy may have numerically superior forces. NCW is the technological embodiment of John Boyd ’s “Observe, Orient, Decide, Act (OODA)” loop concept. To achieve a robust network centric capability, Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach further identifies NCW’s “governing principles”:

- “Fight first for information superiority.”

- Emphasize “high quality shared awareness” through a “collaborative network of networks” through which “information users also become information suppliers.”

- Develop “dynamic self-synchronization” by increasing tactical forces’ abilities to operate autonomously and to re-task themselves based upon shared awareness and the commander’s intent.

- Develop “deep sensor reach” with “deployable, distributed, and networked sensors” and persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

- Accelerate the “speed of command” with compressed “sensor-to-decision-maker-to-shooter timelines.”84

While NCW is as much a behavioral as it is a technical concept, it does possess a distinct technological bend. Therefore, by its very nature, it would necessarily demand improvements in satellites, radio bandwidth, unmanned vehicles, and nanotechnology. John Garstka notes that increasing space-based forces’ responsiveness is particularly important to NCW.85 Citing the “Operationally Responsive Space” concept, Garstka points out that space’s responsiveness would] need to increase from days to hours, or even minutes.86 Furthermore, the NCW concept would have to address long-standing issues associated with joint, coalition, and interagency interoperability.87

The four “pillars” of transformation serve as clear evidence that Rumsfeld understood that Transformation was a continuous process, and therefore needed core truths that guide its growth and adaptation—and serve as the force’s foundation. These truths would function as the long-term, enabling perspective for transformation:

- Pillar One: Strengthening joint operations,

- Pillar Two: Exploiting U.S. intelligence advantages,

- Pillar Three: Concept development and experimentation,

- Pillar Four: Developing transformational capabilities.88

It is clear that Rumsfeld meant to intensify jointness between the services, and even in the interagency and coalition arenas. And in this sense, “modularity” is perhaps a better term. Modularity is not addressed in the Pentagon’s mainstream transformation texts, but it did gain traction with the US Army.89 Modularity is more than simple joint operations, and it goes beyond interoperability. Modularity is the requirement for capability-providers to be jointly-minded enough, and to be interoperable enough, to be successful, especially on minimal or even zero, notice. A “capability provider” could be a single-service, joint, or interagency team that is presented to the Joint Forces Commander (JFC) as a self-contained means. And there may be more than one capability provider per possible capability desired (even though the capability may not be resident in every service). In essence, then, when needed, the JFC would be presented (ideally from US Joint Forces Command) a menu of options through which he can produce the desired operational outcome resulting from his mix of capabilities. The key point is that the menu choices are interoperable, inter-doctrinal, and flexible enough to be successful as an inter-capability team, regardless of which other specific organization is involved. Douglas Macgregor uses the phrase, “plug and play.”90 While close to modularity in concept, it is important to note that capability providers do not have to be the sam e size or operate on similar timelines. They simply have to be interchangeable in reference to output.

This pillar also placed demands on the Department’s acquisition and organization strategies. New capabilities, and their associated platforms, doctrines, and organizations would be “born joint,” and devised in support of four Joint Operating Concepts (JOC): homeland security, stability operations, strategic deterrence, and major combat operations.91 These demands had implications for interoperability in system designs at their outset (vice through post-acquisition retrofit actions), and further reinforces the modularity discussion, above.

As highlighted in the EBO discussion above, intelligence will be a priority. As discussed in the TPG, it serves to provide strategic and operational warning, and is the critical bedrock upon which EBO resides. The TPG further specifies that the US intelligence picture will be persistent and consistent.92 In other words, it needs to provide a continuous data flow, and to produce similar results across the network of users. And with advent of network-centric warfare and speed of command, it will also possess its own modular attributes:

[US intelligence capabilities will] provide horizontal integration, ensuring all systems plug into the global information grid, shared awareness systems, and transformed Command, Control and Communication systems.93

The final two pillars represent the final enduring truths of Rumsfeld’s transformation vision. By leveraging the Pentagon’s cultural change, Rumsfeld hoped to release a continuous process through which the United States will remain ahead of potential adversaries. Concept development and experimentation demands a “competition of ideas.”94 Furthermore, experimentation allows the Department to manage risks associated with the strategic pause’s uncertainty and lack of clearly defined threats. The TPG goes so far as to direct Combatant Commands and the services to develop enduring, formal methods to ensure that new warfighting ways are developed and tested.95 Similarly, the fourth pillar stipulates that these same organizations maintain a formal process through which new capabilities are developed and presented to the Defense Department.

Further illustrating Rumsfeld’s urgency with transformation, the strategy additionally outlined “goals.” As if to prime the transformational pump, these goals represent the initial set of capabilities that would be produced by the pillars, thereby enhancing the new capabilities-based force’s repertoire. Furthermore, goals would strengthen the pillars themselves. At the strategic level, Military Transformation: A Strategic Approach outlines six critical capabilities:

- Goal 1: Protecting critical bases and defeating chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons.

- Goal 2: Projecting and sustaining forces in anti-access environments.

- Goal 3: Denying enemy sanctuary.

- Goal 4: Leveraging information technology.

- Goal 5: Assuring information systems and conducting information operations.

- Goal 6: Enhancing space capabilities.96

All six goals contribute to the umbrella concept of “Deter Forward.” The first three are “mission oriented goals”; the remaining three are “enabling goals.”97 Understanding “Deter Forward” allows one to understand each of these six goals more clearly:

The capability of U.S. forces to take action from a forward area, to be reinforced rapidly from other areas, and to defeat adversaries swiftly and decisively will contribute significantly to our ability to manage the future strategic environment.98

In other words, the Deter Forward concept suggests a swift response to developing scenarios in such a way that the enemy would back off, give up, or become immediately incapacitated, thereby reducing or eliminating the demand of extended deployment and combat operations. As an additional benefit, if the enemy did not respond immediately to these effects, the environment would be favorable to follow-on joint, interagency, or coalition activities.

With this definition, one sees that mission-oriented and enabling goals play a significant role in this concept. Projecting critical bases is the supply side of the equation, whereas projecting and sustaining forces is the equation’s consumption side. The product of this equation then is the third goal, the so-called, “enemy without sanctuary.” The enabling goals contribute in a supporting fashion by providing information, intelligence, and coherent direction to war-fighting organizations via space or cyberspace, shaping the battle-space with these operations by denying the enemy use of these same media. In all, no location in the world would be immune from US abilities to see and analyze the environment, and to insert coherent, unified, and decisive effects into the scenario.

Rumsfeld’s transformation program was not limited by these six goals. The prevalent transformation literature, most notably the TPG, outlined additional goals further supporting each of the four pillars.99 Table 1 outlines the most significant of these new capabilities.

Table 1: TPG Goals In Support of Transformation’s Pillars100

Winners and Losers

A cursory examination of both the strategic and more detailed goals above clearly suggests a technological bias in Rumsfeld’s transformation vision. Furthermore, the program would be expensive. However, Rumsfeld would likely bristle at the suggestion that transformation was a high- tech acquisition program by itself. And to be fair, his vision insists that doctrinal and organizational developments form the bedrock upon which the program rests. He would probably also take issue with the idea of “winners” and “losers” in this process. For when it comes to national defense, the only winners that matter would be the United States, its allies, and its interests. Terry Pudas further observes that in times of uncertainty, the goal is to create “breadth in capabilities first, then generate depth through multiple capability providers.”101 That said, there will logically be organizations, structures, and systems that garner greater departmental and fiscal support under this program than would others—at least in the short term. Table 2 outlines the likely “winners” and “losers,” based upon Rumsfeld’s process and transformation’s desired outputs.

Table 2: Transformation’s Winners and Losers

In order to defer the service-specific discussions until later sections, this table purposefully omits reference to any specific service. Nonetheless, it would be shortsighted to say that some services would not perceive themselves as “losers” more than others under Rumsfeld’s vision. In its broadest terms, however, Rumsfeld’s transformation vision favored systems and organizations that accentuated flat command structures, joint applications and operations, quick action, and emerging technologies and warfighting concepts. Less favored were forces with highly vertical command structures, slow response time, single roles, and large logistical footprints.

Transformation’s Institutionalization

As if understanding transformation were not difficult enough at the departmental level, individual service and US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) interpretations served only to muddle the process further. Failing even to define transformation in the same way, each service and USJFCOM viewed its transformational responsibilities through different prisms and executed transformational efforts differently. The impact of these variances depends upon how one views DOD’s organizational seriousness toward the process. At best, the services and USJFCOM sincerely attempted to address the Secretary’s call and vaguely-defined tasks and outlined future opportunities to engage in a serious joint and interagency debate about transformation’s direction. At worst, these organizations executed transformation as yet another staff project and simply repackaged long-standing acquisition programs as “transformational.” As is usually the case, the truth lies somewhere between these extremes. At this point, however, it would be fair to argue that these variations weakened the public transformational dialogue to the point that elements both inside and outside the Department of Defense focused on what they could (or thought they could) understand. Specifically, the subsequent transformation discussion deteriorated into a debate about system acquisitions, relative budgetary balance among the services, and perceived winners and losers. In spite of some genuinely bright efforts toward improvements in doctrine, education, training, and employment, these achievements bypassed the public’s attention—due to DOD’s collective failure to define and execute transformation succinctly and in an integrated fashion.

This section examines how each service, USJFCOM, and other key players perceived and acted upon the transformation challenge over three periods in Rumsfeld’s tenure as the Secretary of Defense. The first is the period from October 2001 through April 2003, beginning with the 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) and ending with the release of the Transformation Planning Guidance (TPG). The second begins with the TPG’s release, and ends with the release of the 2005 QDR. The final period addresses the period from 2005 through 2007, during which transformation became an unguided event, and lost priority against recapitalization due to extended operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mechanisms for discussion include each service’s “Transformation Roadmaps” and annual posture statements, as well as significant joint and service doctrinal, educational, and training initiatives. The final section will analyze the weaknesses and strengths of the American approach to transformation and provide a prognosis of its continued viability in the post-Rumsfeld era.

2001 through 2003: Transformation’s Initial Steps

Even though transformation’s lineage predates his time as Secretary of Defense, and was a topic during the 2000 presidential campaign, Rumsfeld officially unveiled his vision with the highly anticipated release of the 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR).102 He reinforced this vision with establishment of the Office of Force Transformation (OFT) about a month later. Nonetheless, throughout 2002 and into early 2003, the services pursued transformation with only broad formal guidance. It would not be until April 2003, when OFT officially released its Transformation Planning Guidance, that the services gained concrete, actionable direction.

By summer 2002, OFT produced a draft TPG, but formal release was delayed by inter-service and Secretarial disagreements about the document’s actual role. As noted by an action officer on the Air Force staff, Rumsfeld initially wanted the tasks within this guidance to be a highly directive model for prioritization of budgets, as well as inter- and intra-service actions. Furthermore, Rumsfeld sought to retain final approval authority for what had traditionally been service-specific organize, train, and equip functions. Consequently, each service strongly disagreed with this approach and delayed the TPG’s release through the coordination process.103 They collectively argued that formal forums through which the Secretary was afforded the opportunity to comment upon and shape service actions already existed. These forums included the Strategic Planning Guidance, Future Years Defense Plan, and the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) System, among others. In short, they argued that the TPG provided little additional value to the transformation dialogue.104 It was not until spring 2003 that the Secretary, the services, and OFT resolved these differences and settled on the TPG’s reduced role as a forum for inter-service, USJFCOM, and OFT coordination and reporting on transformation’s progress.

In spite of the lack of formal guidance, the services’ and USJFCOM’s efforts toward transformation hardly languished. Furthermore, each service can easily point to transformational thought and efforts that pre-dated Rumsfeld’s tenure as the Bush administration’s Secretary of Defense. It would be these pre-Rumsfeld thoughts, however, that colored each service’s view of transformation, and initiated the seeds of inconsistency between their respective visions. The fact remains, nonetheless, that the services and USJFCOM understood the Secretary’s earnestness, and, in the absence of formal guidance, initiated their own paths toward transformation by 2002.

While it did not invent the “transformation” moniker, the US Army clearly made transformation a priority starting in October 1999, not long after Operation Allied Force, the bombing campaign against Serbia over Kosovo’s independence effort, came to a close. Regardless of whether one considers the campaign a validation of airpower, the fact that Serbian President Milosevic capitulated in about the same time that it would have taken heavy ground forces to arrive on scene struck a chord with Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki.105 Furthermore, the General was concerned with the fact that these same forces were too heavy for the unimproved roads and bridges found in the region.106 Shinseki’s response to the demand for a lighter, more nimble force identified three priorities: a high-technology, “objective force” to be fielded within 10 years; an “interim force” based upon current technology, and focused upon the service’s “requirement to bridge the operational gap between [its] heavy and light forces”; and modernization and recapitalization of the “legacy force,” the existing platforms and organizations currently within the service.107

The most pressing short term activity was fielding the interim force, which would shortly be called the interim brigade combat team,108 and built around a series of wheeled, moderately armored vehicles produced by General Motors and General Dynamics.109 Longer term acquisitions included design and fielding of the “Future Combat System,” the Comanche helicopter, and multiple Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) upgrades, all in support of the objective force.110 The legacy force would be buttressed with acquisition of the Crusader self-propelled howitzer, and upgrades to the Army’s fleets of helicopters, the M1 Abrams Tanks, and the M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles.111 And finally, understanding that “transformation applies to what we do, as well as how we do it,” Shinseki also introduced a series of manpower, education, training, and readiness initiatives.112

Although highly contested in defense circles,113 the Air Force’s self-proclaimed preeminence in Operation Allied Force resulted in a sense of urgency notably less intense than the Army’s. While appreciating that an RMA was underway, and embracing Joint Vision 2020’s concepts, the traditionally technology-focused service did not truly address transformation as a coherent, organizational priority until 2002.114 That said, elements of transformational thought were clearly evident before that time. For example, future USAF Chief of Staff General John Jumper, as the USAF’s Air Combat Command Commander, unveiled his vision for the Global Strike Task Force (GSTF) in the spring 2001 edition of Aerospace Power Journal. What would eventually be one of six capability-specific task forces, GSTF was a pre-packaged, quick response, strike organization built around the Air Expeditionary Force model, a series of sensor and command nodes, and the F/A-22. GSTF would be, in the General’s words, the USAF’s “contribution to the nation’s kick-down-the door force.”115 Similar to the Army, the Air Force consistently, throughout the 1990s and beyond, addressed several training and education, retention, infrastructure, personnel initiatives as part of its strategic message. While not outlining short, moderate, and long term goals, the Air Force’s acquisition priorities included the F/A-22, the space-based laser, miniature satellites, multiple unmanned aerial vehicle systems, and several C4ISR upgrades. In addition to these acquisition priorities, the USAF demonstrated transformational thinking by refining its Air Expeditionary Force concept from the 1990s, by designating the Air Operations Center as a command and control weapon system in its own right, and by initiating greater active duty, Air National Guard, and USAF operational integration.116

By the time the USAF released its posture statement in 2002, however, transformation was a clear priority. The document devoted an entire section to transformation, and presented the GSTF and the other initiatives discussed above in a transformational light. Unlike the Army, and consistent with its confident perspective, the USAF’s 2002 statement’s core message remained focused upon recapitalization and strengthening the service’s core competencies, as opposed to organizational or doctrinal adjustments.117

Although the Navy participated in Operation Allied Force, it was not the clarifying moment it was to the Army or the Air Force. Furthermore, the Navy, more than the Army and the Air Force, can argue that they consistently sought to harness the opportunities of the post-Desert Storm RMA, even though they did not use “capital ’T’ transformation terminology” until much later.118 In late 1992, with its publication of From the Sea, the Navy formally shifted its efforts away from Cold War “blue water” engagements with Soviet Union to a new series of littoral scenarios.119 To reflect this new focus, the service initiated the DD(X) Destroyer program,120 and began to modify its training and equipment concepts to reflect greater joint operations, albeit primarily with the US Marine Corps. For the Navy’s role in these operations, it placed greater emphasis on amphibious warfare, mine warfare, and defenses against diesel-electric submarines and small surface craft121—a perspective that they likely thought was validated by the attack on the USS Cole in 2000. Additional priorities included unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV), as well as expanded use of stealth technologies, starting with the Joint Strike Fighter.122

Beyond its focus upon littoral operations, the Navy was really the first service to embrace Network Centric Warfare (NCW). Toward this end, it outlined the FORCEnet concept as part of its 2002 program guide, Vision… Presence… Power:

The FORCEnet combat capability will exploit state-of-the-art information and networking technology to integrate widely dispersed human decision makers, situational and targeting sensors, and forces and weapons into a highly adaptive, comprehensive networked system to achieve unprecedented mission effectiveness and battle force readiness. FORCEnet is the integrated system comprised of force components, the warfighters in the force embedded within an information network. The comprehensive FORCEnet System integrates and operationally couples warfighters, sensors, weapons, command, control, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and information infrastructure assets into combat capabilities that enable NC[W] and ensure information dominance across the Navy's entire mission spectrum. FORCEnet will enable battlespace dominance through comprehensive knowledge, focused execution, and coordinated sustainment shared cross fully netted maritime, joint, and combined forces.123

The Navy also mentioned FORCENet in Naval Power 21 as the integrating backbone of its operating concepts, “Sea Strike,” “Sea Shield,” and “Sea Basing.”124 These three concepts emphasized the unique capabilities of naval forces especially with regard to homeland defense and anti-access missions. They accompanied “Sea Warrior” as its training and education program; “Sea Trial” as its experimentation program; and “Sea Enterprise” as its business improvement program.125

Finally, USJFCOM pursued its role as transformation’s strategic experimentation arm, most notably with the exercise, “Millennium Challenge 2002.” In the command’s own words,

Millennium Challenge 2002 is this nation's premier joint warfighting experiment, bringing together live field forces and computer simulation…. [exploring] how effects based operations (EBO) can provide an integrating, joint context for conducting rapid, decisive operations (RDO). Featuring live field exercises and computer simulation, [Millennium Challenge 2002] will incorporate elements of all military services, most functional/regional commands and many DOD organizations and federal agencies, using the largest computer simulation federation ever constructed for an experiment of its kind.126

Clearly, each service and USJFCOM understood transformation’s importance, the Secretary’s likely emphasis upon the process, and demonstrated concrete action, although often based upon concepts generated in the 1990s. While the period from the QDR to the TPG cannot be construed as an idle period, it was nonetheless in this interim period that the seeds of dissimilarity would be sown. All four organizations acknowledged the RMA’s existence. However, at the organizational level, there was variance in how they understood the “strategic context.” And in this sense, one must take a narrower view of “strategic context.” Certainly, they all understood that the Cold War was over. For the Army, however, the strategic context included questions about the service’s continued relevance. The Air Force perceived the new era as one in which its preeminence was nearly self-evident. Judging from the US Navy’s doctrine and publications, one could see the service’s self-image as a founding organization of transformation, NCW, and jointness. And as a result of this image, it was the other organizations’ responsibility to catch up. USJFCOM saw transformation as an opportunity to explore simulations and experimentation within its role as one of the joint community’s brain trusts.

The Process in Execution: 2003 through 2004

As several Pentagon staff officers commented, Secretary Rumsfeld’s Transformation Planning Guidance (TPG) forced the services to describe their respective transformation visions in a concrete manner, and to understand their roles as part of a larger joint team.127 And if the product served no other role, it proved itself valuable to the transformation dialogue. To that end, the TPG placed transformation’s primary thrust in the hands of OFT, USJFCOM, and the services. Key to the process was production of annual transformation “roadmaps” by each service and USJFCOM, and production of a “Strategic Transformation Appraisal” by OFT.

Among the roadmap-specific tasks presented to the services, the most significant are the following:

- “Use the definition of transformation presented [in the TPG].”

- Specify “when and how capabilities will be fielded.”

- “Identify critical capabilities from other services and agencies required for success.”

- Identify changes to organizational structure, operating concepts, doctrine, and skill sets of personnel.”

- Devise “metrics to address the six transformational goals and transformational operating concepts.”128

For OFT, its responsibility to “monitor and evaluate implementation of the Department’s transformation strategy, advise the Secretary, and manage the transformation roadmap process”129 was reflected in the requirement to provide Rumsfeld a “Strategic Transformation Appraisal”:

The transformation process will be evaluated in an annual appraisal to be written by the Director, OFT and submitted to the Secretary of Defense no later than January 30. These appraisals will evaluate and interpret progress toward implementation of all aspects of the transformation strategy, recommending modifications and revisions where necessary.130

To be sure, there were a myriad of other tasks,131 but for the services, USJFCOM, and OFT, the TPG identified a formal vision-analysis-reporting cycle as the most significant of their responsibilities. The Secretary, and to some degree, the services and USJFCOM owned the vision. Analysis and reporting would be an inter- and intra-organizational effort among USJFCOM, the services, and OFT.

By insisting that the Department’s definition of transformation be used, it is clear that Rumsfeld understood the definition’s potential to introduce dissent, and to degrade the dialogue into an argument over terms. In order to avoid such an outcome, the TPG offered a baseline definition, but with little additional language as if to avoid contextual interpretations:

Transformation is “a process that shapes the changing nature of military competition and cooperation through new combinations of concepts, capabilities, people and organizations that exploit our nation's advantages and protect against our asymmetric vulnerabilities to sustain our strategic position, which helps underpin peace and stability in the world.”132

While the easiest approach to compliance would be simply to use the TPG’s definition, word-for- word, this methodology was not directed in the TPG. And there are indeed inconsistencies between the services. It is likely, nonetheless, that Rumsfeld would insist that the major components be addressed in each service’s definition. Those components include the following:

- Identification of transformation as a process that attempts to shape the calculus of military competition and cooperation

- Involves combinations of concepts, capabilities, people and organizations

- Exploits national advantages

- Protects against asymmetric vulnerabilities

- Looks to sustain the American strategic preeminence