Chapter 9: Russia and the Middle East: Opportunities and Challenges

Introduction

Russian influence and presence in the broad Middle East (North Africa, the Levant, and Persian Gulf) have significantly fluctuated over the last several decades.1 In the 1960s and early 1970s the Soviet Union established strong ties with Egypt, Iraq, Syria and South Yemen. Since the late 1970s, Egypt, a leader of the Arab World, has changed sides and became a close U.S. ally. In the 2020s, Iraq is a very different country than it was in 1970s. The war with Iran (1980-88), occupation of Kuwait (1990-91), toppling of the Saddam Hussein regime (2003), and finally the fighting with the Islamic State, (ISIS) have eroded both economic development and political stability. More or less, the civil war in Syria since 2011 has left the country in a similar dire position like Iraq. South Yemen ceased to exist in May 1990 when it was officially united with its northern neighbor. The devastating war since 2015 means the future of the country is very uncertain.

On the other side, the Soviet Union was dissolved in late 1990 and the emerging Russia needed some time to reorganize and stabilize in order to establish itself both economically and politically. Predicting Russia’s behavior has always been difficult, but it has become even more so over the past several years. The 2008 war with Georgia, the 2014 intervention in Ukraine, and the 2015 Syrian campaign caught policymakers and analysts off guard. The Kremlin has made an art out of surprising the world with audacious gambits on the global stage.2 It is clear that Russia has embarked on a more assertive and militaristic foreign policy in the Middle East and elsewhere. Behind this assertiveness is a desire to re-establish Russia as a global power.

Russia’s approach to the Middle East may appear to be a winning strategy that is presently reaping dividends. However, the approach is not without significant challenges and risks. This chapter briefly highlights Moscow’s main interest in the region and how it has pursued these interests since the early 2000s. The analysis focuses on the major economic and political drivers of both Russia and Middle East powers in forging strong ties and how they perceive each other. The essay examines how the two sides have utilized energy deals and arms sales to achieve their strategic objectives. Finally, the paper discusses how the growing Russian presence in the Middle East is likely to impact the United States’ strategic interests in the region.

Russia and the Middle East – Background

Initially, the Soviet Union rhetoric against imperialism and the West appealed to a number of Arab governments who championed independence from colonial powers and embraced a state-led economy: Libya, Egypt, Syria and Iraq. Generally, the Soviet model failed to meet the aspirations of the Arab and Persian peoples and governments while the Soviet Union adopted a less confrontational approach toward the West and the United States in the decade prior to its disintegration. In the 1990s, under Boris Yeltsin, Russia needed a space to re-group and re-consider its foreign and domestic priorities. The nation lacked the resources and even the will to be an active player in the Middle East. President Vladimir Putin (in power since 1999) has played a key role in bringing a sense of political stability to his country. His efforts were boosted by high oil prices since 2014.

Drivers of Russian Policy in the Middle East

Moscow’s assertive approach to the Middle East since the early 2000s has been largely driven by strategic and economic concerns. Similarly, regional powers have their own reasons to engage with Russia. First, in 2005 President Putin described the breakup of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geo-political catastrophe of the twentieth century.”3 He has never hidden his ambition to “restore” Russia to the status of global power. The days when Moscow could entice allies through ideology are over. Instead of attraction and persuasion, Russia has pursued hard diplomacy, economic inducements, military force, and other coercive measures. Thus, Russia has been able to demonstrate to the U.S. and the EU that it plays a crucial role in ongoing international conflicts. The country has established itself as a key player in Syria, Libya, and negotiations with Iran as well as having extensive ties with Turkey and Israel. The so-called “Arab Spring” since 2011 has presented Russia with both significant security risks and geo-political opportunities. The Kremlin has viewed the uprisings in several Arab countries as a re-play of the so-called “color revolutions,” i.e., the toppling of pro-Moscow governments in Eastern Europe. Russian leaders have sought to block this bitter experience and stop what they consider a “Western plot” against Russia’s national interests. A close examination of the Russian role in regional conflicts suggests that Moscow might not be able to force particular outcomes, but it is likely to be able to raise the cost to the West of pursuing specific policy options that are not in line with its wishes.

Adapting an assertive foreign policy approach can serve to boost stability and legitimacy at home. In the last several years, Russia has been subject to European and American sanctions. Close cooperation with Middle Eastern countries can serve to offset the negative effects of these Western-imposed sanctions. Russia has a large Muslim minority and several Islamic countries in its near abroad, i.e., the Caucasus and Central Asia, are predominantly Muslim. Accordingly, Russian leaders have long perceived Islamic ideology and Islamists as significant threats. Within this context, warm relations with Muslim countries in the Middle East and elsewhere would enhance the Russian government’s image among its Muslim population and would enable Moscow to contribute and shape the war against extremist groups in Syria and other Middle Eastern countries.

Economic interests are also a major driver of Russian foreign policy. Although the volume of trade between the two sides is relatively low, particularly in comparison with other global powers such as the United States, the European Union, and China, economic ties between Moscow and several regional powers have expanded since the early 2000s. Russia’s major exports to the Middle East include military equipment, machinery, oil and gas, petrochemical, metallurgical, and agricultural products. The Middle East is the main destination for exports of Russian grains. In order to further boost trade relations, Moscow has occasionally offered to use national currencies as a legal tender in bilateral trade instead of euros and U.S. dollars and has invited its Middle East trade partners to form a free trade zone with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Investment is another major area of on-going cooperation between the two sides. Middle East oil producers own some of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world. They want to diversify their investment portfolio to include other major markets in addition to those of Western Europe and the United States. Moscow seeks to attract some of these investments.

Both Russia and several Middle Eastern countries are major oil and gas producers and exporters. A long time ago, the two sides decided that cooperation, rather than confrontation, would serve their mutual interests. Major Russian energy companies, such as Rosneft, Lukoil, Gazprom, Surgutneftegaz, and Tatneft, have made substantial investments in oil and gas sector in the Middle East. Russia is not a member in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) but for several years has coordinated its production policy with the Vienna-based organization. Generally, the two sides (Russia and OPEC) seek to maintain oil price stability and offset the growing volume of US oil production. Similarly, Russia, along with several Middle Eastern countries, is a founding member in the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF), which has similar goals to those of OPEC.

Arms deals have always been the cornerstone of Moscow-Middle Eastern relations since the time of the Soviet Union. Most regional powers prefer Western over Russian arms. However, at least two challenges have always complicated arms supplies from the United States and Europe: A) concern about human rights and B) maintaining Israel’s qualitative military edge. As a result, some Middle Eastern countries perceive Western governments as unreliable source of weapons. Russia, on the other hand, does not impose such restraints on its arms deals. In the late 2010s, Russia has been able to secure a major arms deal with Turkey, a NATO member, by selling it the SAM-400 air defense system, despite strong opposition from the United States and the threat of sanctions, which were eventually imposed in December 2020.

The growing relations between Russia and Middle Eastern countries reflect perceived benefits by the two sides. Leaders with regional influence, based on cost-benefit analysis, are generally eager to do business with Moscow. At the end of the day, they do not want to be taken for granted by Washington; Russia is seen as an alternative to the United States. Similarly, presenting Russia as an option can be used to pressure the United States to adopt a desired course by Middle Eastern countries. Moscow promotes its approach to the Middle East as secular, transactional, and non-ideological.4 When Middle Eastern leaders doubt Washington’s commitment and obligations, they find a partner in Russia. This was clear under the Obama Administration, and more recently, when Congress denounced the killing of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2019.

Limitations on Russian Middle East Policy

Undoubtedly, Russia has many ways it can benefit from involvement in the Middle East. As the previous analysis shows, the two sides can provide each other with strategic and economic opportunities. However, this ambitious desire to deepen mutual engagement confronts serious challenges. First, there is a huge mismatch between Moscow’s strategic objectives and its economic resources. Unlike Middle Eastern oil exporters, the Russian economy is not deeply dependent on oil and gas revenues, though these revenues do represent a large proportion of state budget. Low oil prices since 2014, and European and American sanctions, have limited Russia’s capacity to exercise influence abroad. Arab Gulf states have identified Russia’s current economic need as a weakness that they can exploit for their own political gain. Currently, Russia’s financial and economic capabilities do not match those of the U.S. and EU and are not likely to do so in the foreseeable future.

Second, Russia’s efforts to expand its influence in the Middle East pose another major challenge. In 2007 the state television channel Russia Today (RT) launched its Arabic service, which covers not only the Middle East but also Europe. These efforts were supported by the Russian federal agency Rossotrudnichestvo, whose official aim is to develop the country’s cultural presence abroad. By 2014, it had created a network of missions in the capitals of Syria, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt.5 These efforts, however, have only made incremental gains in altering narratives in the region. Russia’s soft power still has a long way to develop in order to be able to compete with that of the United States and Europe. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), France 24, and Voice of America hold more resources and enjoy more credibility than RT.

Third, despite limited economic resources and soft power, Russia has managed to establish and maintain relations with almost all major regional powers including Egypt, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Israel, and Hamas. Indeed, President Putin is one of the few world leaders who has met with the Ayatollah Khamenei of Iran, Crown Prince Mohammad bin-Salman of Saudi Arabia, and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel. The Russian president also maintains close ties with both the Turkish President Erdogan and his Syrian neighbor Assad. These relations with states and non-state actors who are at odds with each other have their own limitations. Russia finds itself walking a tightrope to balance all these regional powers. For example, Moscow has had a hard time balancing its close ties with Israel, Iran, and Assad in the on-going fighting in Syria. Another challenge is that this impartiality limits the depth of Russia’s bilateral relations. Finally, if the hostility further intensifies between these regional powers, Russia might be forced to choose sides.

Fourth, Russia does not only compete with the United States and Europe over influence in the Middle East, it competes with China as well. Unlike Moscow, Beijing has so far chosen to avoid any security role similar to the Russian presence in the Syrian civil war and more recently in the Libyan civil war. But, China enjoys key advantages over Russia. It controls substantial economic and financial resources and in recent years has become the main trade partner to several Middle Eastern states. Equally important, China is the main consumer of oil and gas exports from the Persian Gulf. On the other hand, Middle Eastern leaders have been using close ties with Beijing to show Washington, Brussels, and Moscow that they have other options.

Case Study 1: Syrian Civil War

The Assad regime’s close relations with Moscow are the oldest in the Middle East. When he was Defense Minister, Hafez Al-Assad established warm ties with the Soviet Union, which he maintained and further strengthened after he became president and his son Bashar followed suit. Given this history, Moscow has three strategic goals in the Syrian civil war:

- To preserve the Assad regime as a major ally and maintain Russia’s air base in the western province of Latakia and its naval base in the port of Tartus (Russia’s direct access to the Mediterranean Sea);

- To defeat Islamic extremist groups, which are, in Moscow’s eyes, an extension of the terrorist groups it fights in Chechnya, Dagestan, and other parts of the country;

- To use Damascus as a springboard to expand its influence in the Middle East, project power, and challenge U.S. regional and global dominance.

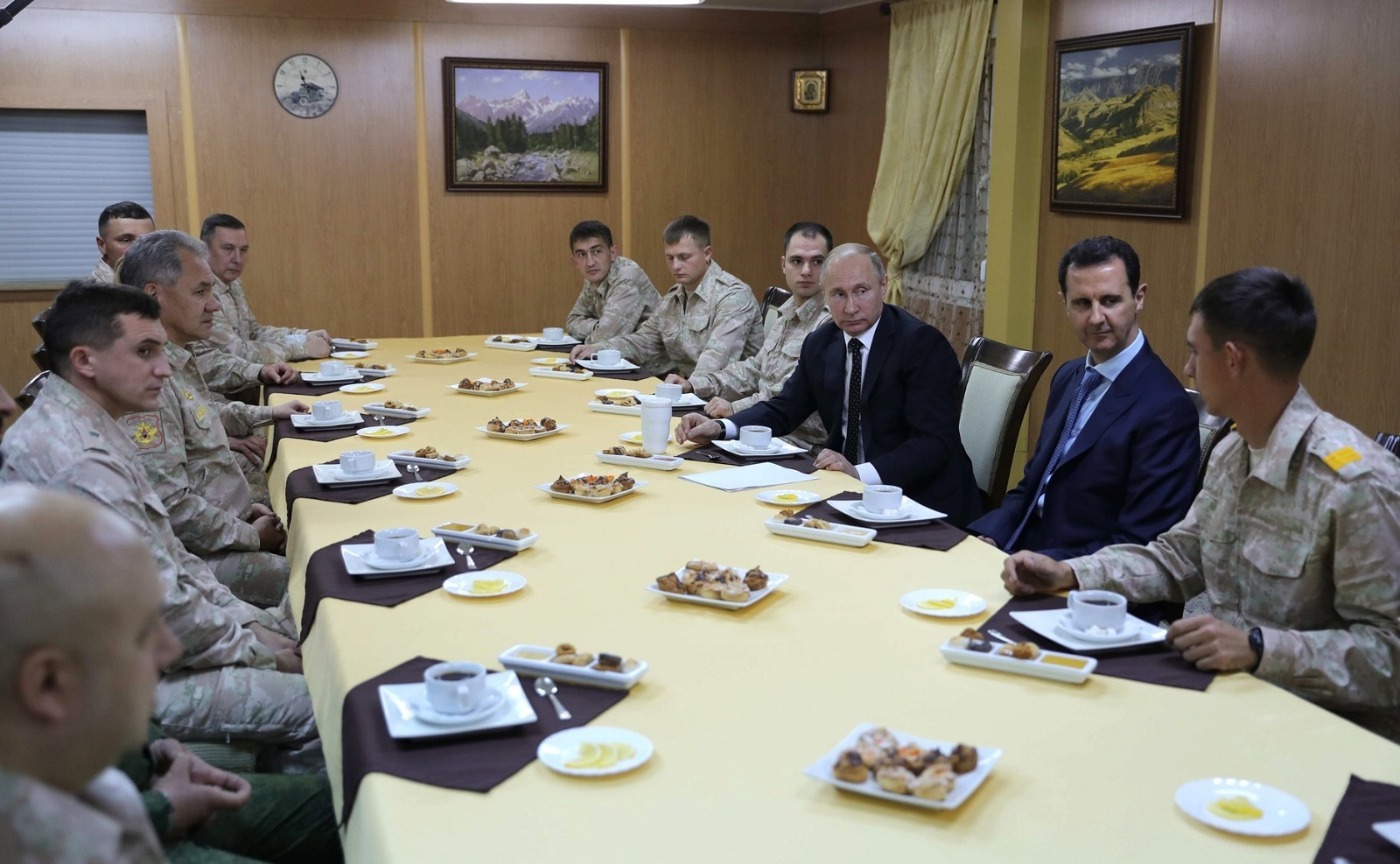

In pursuing these objectives, Russia started a massive military intervention in Syria, the first outside of Europe since the end of the Cold War. Starting in October 2015, Russia has provided significant military and political support to President Assad. Russian air strikes against his opponents have turned the tide of the war in favor of the Syrian government and established Moscow as the main global military power in the country. By deploying the S-400 cutting-edge air-defense system, Moscow controls most of the air space in Western Syria.

Russia’s relations with Iran and its perception of Tehran’s role in the Syrian war are complicated. Relations between the two are driven more by shared geopolitical considerations than by economic interests. Arms sales and political support are major drivers of the alliance between the two nations, whereas economic ties are anemic; Tehran has a much larger volume of trade with Asian powers, particularly China, and with the EU. Moscow and Tehran are simultaneously allies and competitors. In the Syrian war the two nations need each other, but their strategic objectives are not identical. They both fight against Sunni rebel groups supported by regional and Western powers. Both Russian air power and Iranian influenced Shiia militia ground forces are essential to win this fight, but Tehran insists on a military victory and wants to establish a permanent presence along Israel’s borders. Moscow, on the other hand, is more open to a political compromise; after securing its military bases, it wants to bring its troops home. A decisive victory by President Assad and his Iranian, Hezbollah, and other allies might not be the outcome Russia would like to see in Syria. Moscow seeks to balance its strategic relations with Tehran with those of other regional powers. Specifically, Russia has adopted an accommodative approach to Israel’s security concerns.

Since the beginning of the Syrian war, Prime Minister Netanyahu has met with President Putin more often than he has met with American presidents. The two countries have a de-confliction mechanism in place, allowing Israeli jets to strike Iranian targets in Syria without simultaneously hitting Russian forces. Meanwhile, Russia has not used its advanced anti-aircraft batteries to stop the Israeli attacks. This suggests that Moscow has either given Jerusalem a green light or is turning a blind eye to air strikes against Iran/Hezbollah targets. Russian officials have been calling for restraint from all parties, but Moscow’s reluctance to take a strong stand against Israeli air strikes indicates a desire to avoid confrontation with Jerusalem and a willingness to tolerate some degradation of Iran’s capabilities in Syria.

The rising tension between Tehran and Jerusalem has put more pressure on Moscow to find a balance that will accommodate their opposing strategic objectives. Iran and its Shiite-militia allies want to maintain a military presence in Syria to deter potential Israeli aggression against the Islamic Republic. Jerusalem rejects such a scenario and has launched military operations to prevent it. Given its heavy military involvement in the Syrian war and its close relations with both Iran and Israel, Moscow is well-positioned to negotiate a compromise. Russia does not want the fighting between these sworn enemies to escalate and further destabilize Syria (and the entire region), delaying the withdrawal of Russian troops. Against this background, President Putin stated that foreign armed forces will withdraw from Syria.

There is a problem, however: it is not clear whether the Assad regime is strong enough to survive without Russian and Iranian support. A premature withdrawal might force Assad to give up some of the gains he has recently won from opposition groups. Furthermore, it is not clear that Tehran will accept the Russian proposal. President Putin’s call was followed by a modification from Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who said that only Syrian forces should be stationed on the country’s southern border, implying that Iranian and Hezbollah forces should be ruled out. This modified proposal amounts to the creation of a buffer zone along the Israeli-Syrian borders. Iranian-allied Shiite forces would not be allowed in this zone, so the launching of short-range missile attacks on Israel would diminish.

Case Study 2: Nuclear Power

One of the growing areas of expanding Russia influence in the Middle East is the construction of nuclear power plants. Russian leaders see the transfer of civilian nuclear technology as an important tool for projecting influence overseas. In 2014 Russia signed a package of agreements for the construction of up to eight new nuclear reactors in Iran. The first two are expected to be built in Bushehr, which Russian engineers had already built and handed over to national authorities in 2013. During Putin’s February 2015 visit to Egypt, Rosatom signed a contract for the construction of Egypt’s first nuclear power plant. In March 2015, Russia and Jordan signed a $10 billion agreement allowing Rosatom to build and operate two nuclear reactors with a total capacity of 2,000 megawatts. In September 2019, Russia signed a $20 billion agreement to build four nuclear power reactors in Akkuyu, Turkey, one of the largest nuclear deals in the world.

Russia is boosting its dominance in new nuclear sales. Currently, it leads the pool of global suppliers, accounting for two-thirds of the globally exported nuclear power plants under construction.6 Since the 1950s, global powers have been interested in exporting nuclear power for a number of strategic benefits, including securing a source of domestic power generation, the ability to establish nuclear safety and nonproliferation standards around the world, enforcing a vibrant nuclear innovation ecosystem, and some degree of geopolitical influence with other nations. These strategic benefits, along with the value of nuclear power as a source of low greenhouse gas-emitting energy in the fight against climate change, become important to understanding the dynamics of Great Power Competition and Moscow’s growing role in the Middle East. Nuclear commerce entails not only a multi-year effort for reactor construction but also an ongoing relationship between a supplier country and a recipient one regarding fuel supplies and reactor maintenance. As such, nuclear commerce serves to create or maintain diplomatic, commercial, and institutional relationship. This is where the link between nuclear commerce and geopolitics exists on multiple levels.

Russia’s nuclear energy sector is organized under a single player, Rosatom (established in 2007). It serves as the direct arm of the state for both civilian and military nuclear energy work. The corporation is entirely under the control of the Russia state, with its strategic objectives being set by President Putin.7 Russia’s rise as the dominant reactor technology supplier can be explained by its ability to adapt its business model to a changing market. Rosatom is both vertically and horizontally integrated, providing reactor technology, plant construction, fuel, operational capability (including training), maintenance services, decommissioning, spent nuclear fuel reprocessing and regulatory support, as well as generous financing (debt and equity) to both established markets and newcomers. This integrated structure gives Russia the ability to engage a foreign client through a single point of contact in contractual engagements. The one-stop-shop approach has a particular appeal to newcomer countries (such as those in the Middle East) that lack adequate experience in developing such complex projects.8

Rosatom’s nuclear project at Akkuyu in Turkey added a strategic value to Russia by further complicating relations between Ankara and Washington. Although Turkey has had a bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States since 1955, political instability and economic crises combined with Ankara’s insistence on commercially difficult terms have confounded the Turkish government’s efforts to sign a nuclear deal with an American company. The agreement with Rosatom aims to build the country’s first nuclear reactor on the build-own-operate (BOO) model by the early 2020s. Under such a model, Russia would not only build but also own and operate the plant, thereby bearing all the financial, construction, operating and country risks. This arrangement aims to remove many technical and regulatory barriers a nuclear newcomer may encounter in introducing nuclear energy and has likely reduced a significant level of financial barriers for Turkey. Meanwhile, these close ties between Ankara and Moscow have further complicated relations with Washington and other European powers.

Implications for the United States and Recommendations

Two weeks after inauguration, President Biden visited the Department of State and gave his first foreign policy speech. The president said, “The days of the United States rolling over in the face of Russia’s aggressive actions are over. We will not hesitate to raise the cost on Russia and defend our vital interests. We will be more effective in dealing with Russia when we work in coalition and coordination with other like-minded partners.”9 This statement from President Biden indicates that his Administration plans to reach out to European allies to confront Moscow around the world.

Russia has always sought to export a different worldview to Middle Eastern countries than Western powers have projected. This model has always reflected ideological orientation and perceived national interests. Moscow has never shown interest in supporting transparency and democratic values and has always endorsed authoritarian leaders. Like the Chinese model, it focuses more on transaction and less on transparency and rule of law. As such, it appeals to many Middle Eastern governments. Within this context, several points should be highlighted:

- Despite lucrative energy and arms deals, Russia’s priorities are closer to home, i.e., Europe and Asia.

- Russia’s growing role in the Middle East is guided by pragmatism and opportunism and not driven by any ideological orientation. Authoritarianism and totalitarianism are the form of ideology Russia tolerates and promotes in the Middle East and elsewhere.

- There is no doubt Moscow has expanded its influence in the Middle East since the early 2000s. However, one can argue, Russian rising role is unsustainable given the nation’s limited hard and soft resources.

- Middle Eastern leaders have always sought to play Russia off the United States. This is not likely to change. However, they perceive Washington as their primary security, economic, and strategic choice.

- Russia has demonstrated capabilities less to dictate outcomes and more to complicate American policies. This is likely to continue in the foreseeable future.

- Leaders and policymakers should understand that Russia both considers the Middle East a secondary priority and cannot sustain continued growth in influence. Therefore, what it offers the Middle East is short-term opportunity rather than long-term security, and the U.S. and its allies can bring something to the negotiating table that Russia cannot.

- Russian-Middle Eastern ties will continue focusing on arms sales and energy. The two sides need each other. Most Middle Eastern countries prefer to buy American weapons, but when Washington imposes political restrictions on arms sales, Russia is seen as an option. For several years, major oil producing countries have coordinated their production policies with Russia in what is known as OPEC +. The two sides both seek to prevent oil prices from declining and to undercut U.S. fracking efforts. The Biden Administration’s focus on climate change and its support to clean energy is likely to weaken the OPEC-Russia partnership. The global demand for oil will continue, but is projected to decline in the coming years.

- Understanding this, the U.S. should seek to provide a steadfast presence that promotes rule of law – countering the short-term disruptive acts of Russia.

For Academic Citation

Gawdat Bahgat, “Russia and the Middle East: Opportunities and Challenges,” in Russia’s Global Reach: A Security and Statecraft Assessment, ed. Graeme P. Herd (Garmisch-Partenkirchen: George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, 2021), https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/marshall-center-books/russias-global-reach/chapter-9-russia-and-middle-east-opportunities-and-challenges, 72-79.

Notes

1 John Raine, “Russia in the Middle East: Hard Power, Hard Fact,” IISS, last modified October 25, 2018, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2018/10/russia-middle-east-hard-power.

2 Fredrik Wesslau and Andrew Wilson, “Russia 2030: A Story of Great Power Dreams and Small Victorious Wars,” Report, European Council on Foreign Relations, 2016, accessed December 17, 2020, doi:10.2307/resrep21534.

3 Andrew Osborn, “Putin: Collapse of the Soviet Union Was Catastrophe of the Century,” Independent, October 6, 2011, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/putin-collapse-of-the-soviet-union-was-catastrophe-of-the-cenutry-521064.html.

4 Becca Wasser, The Limits of Russian Strategy in the Middle East (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019). https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE340.html.

5 Nikolay Kozhanov, “Russian Policy across the Middle East: Motivations and Methods,” Chatham House, February 21, 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/russian-policy-across-middle-east-motivations-and-methods.

6 “Performance in 2018,” Rosatom, accessed April 5, 2020, https://rosatom.ru/upload/iblock/0c1/0c106b40899f365fd8c2a6be935b092b.pdf.

7 Nevine Schepers, “Russia’s nuclear energy exports: status, prospects and implications,” EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Consortium, February, 2019, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/eunpdc_no_61_final.pdf.

8 Jane Nakano, “The changing geopolitics of nuclear energy,” Report, CSIS, March 12, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/changing-geopolitics-nuclear-energy-look-united-states-russia-and-china.

9 President Joseph Biden (2021) Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/04/remarks-by-president-biden-on-americas-place-in-the-world/, accessed February 4, 2021.

About the Author

Dr. Gawdat Bahgat is a professor at the Near East-South Asia Center for Strategic Studies (NESA) at the National Defense University in Washington, DC. He is the author of twelve books and more than 200 articles on the Middle East. His areas of expertise include energy security; proliferation of weapons of mass destruction; international political economy; Iran; and U.S. foreign policy.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, a German-American partnership, is committed to creating and enhancing worldwide networks to address global and regional security challenges. The Marshall Center offers fifteen resident programs designed to promote peaceful, whole of government approaches to address today’s most pressing security challenges. Since its creation in 1992, the Marshall Center’s alumni network has grown to include over 14,400 professionals from 156 countries. More information on the Marshall Center can be found online at www.marshallcenter.org.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, the U.S. Department of Defense, the German Ministry of Defense, or the United States, German, or any other governments. This report is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.