Ukrainian Membership in NATO: Benefits, Costs and Challenges

Introduction

In conformity with Article 51 of the UN Charter, the NATO-Ukraine Charter on a Distinctive Partnership, recalls that it is, “the inherent right of all states to choose and to implement freely, their own security arrangements, and to be free to choose or change their security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve.”1

In the case of both NATO and Ukraine, each must determine whether membership is in their interest. For NATO, the primary requirements are spelled out in Article 10 of the Washington Treaty2 and further addressed in the 1995 Study of Enlargement and the Membership Action Plan.3 In addition, NATO and Ukraine have agreed to specific objectives for Ukraine which are spelled out in detail in the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan, and since 2002 these specific objectives have been implemented in accordance with Annual Target Plans. Starting in 2002, Ukraine has also sought participation in the Membership Action Plan, which is seen as an essential step towards membership, but progress has been limited to an Intensified Dialogue, launched in April 2005.

At the moment, the issue of Ukrainian membership in NATO is on hold for a number of reasons including: (1) radically divergent opinions within the government (between the President and the Prime Minister) on the desirability of Ukraine seeking NATO integration (among many other issues), (2) lack of public support in Ukraine, (3) the need for considerable further reform, (4) the continuing complexity, fractiousness and uncertainty of the Ukrainian political process and disagreement over foreign policy prerogatives,4 (5) differing views among allies about Ukrainian membership in NATO and (6) Russian pressure.

Looking to the evolution of these issues, I address in this paper the benefits that Ukraine could expect to derive from NATO integration as well as the costs of membership and some misconceptions, usually advanced by critics of Ukraine’s NATO aspirations. For completeness, I also highlight some of the key challenges that Ukraine is facing regarding NATO membership. Key benefits would include, collective defense guarantees, defense at lower cost, participation in cooperative security arrangements, decision making in NATO, continuing impetus to reform, a possible boost for EU membership, strengthening Ukraine’s position vis-à-vis Russia and increased economic growth and foreign direct investment.

The issue of Ukraine’s integration in NATO is an important one. It involves the question of how far NATO will go in enlarging into the former Soviet space and what security arrangements Russia will develop to assure its own security. In addition, the issue is one of the determining factors in NATO-Russia relations.

State of Play

NATO-Ukraine relations were formally launched in 1991, when Ukraine became a founding member of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC, later transformed into the EuroAtlantic Partnership Council (EAPC)). In 1994, Ukraine became the first Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) member to join Partnership for Peace (PfP).

NATO and Ukraine have been clear about the importance of their special relationship which was spelled out in the Charter on a Distinctive Partnership between NATO and Ukraine in 1997. Inter alia, the Charter emphasizes the importance of an independent, democratic and stable Ukraine as a key factor to ensure stability in the Euro-Atlantic area.5 Just before the fifth anniversary of the Charter, in May 2002, President Leonid Kuchma announced Ukraine’s goal of eventual NATO membership, which led to the adoption of the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan by Ukrainian and allied foreign ministers in Prague in November 2002. However, the Kuchma government’s motives and commitment were suspect, partially due to a number of high-profile scandals.

The situation changed dramatically with the Orange Revolution. Following the 2004 elections, NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoppe Scheffer stated that, “Our overriding goal – to assist Ukraine to realize its Euro-Atlantic aspirations and to promote stability in the region – remains unchanged.”6 Ukraine’s importance to NATO was reflected in the Secretary General’s attendance at President Yushchenko’s inauguration on 23 January 2005 and President Yushchenko’s visit to a separate meeting with allied heads of state and government during the NATO 22 February 2005 Summit. The next important step was the initiation of the Intensified Dialogue (on Membership) in April 2005, which was “a clear signal that NATO Allies supported Ukraine's integration aspirations.”7

Admission of Ukraine to membership action (MAP) status, now seen as a necessary step to membership, was being considered positively in the run up to the NATO Riga Summit in November 2006 and was expected to be agreed, according to some observers. However, this idea was subsequently dropped in light of the Prime Minister Yanukovcyh’s statement to the North Atlantic Council on 14 September 2006. At that time Prime Minister Yanukovych stated, “There is no alternative today for the strategy that Ukraine has chosen in its relations with NATO,” But regarding the Membership Action Plan, because of the political situation in Ukraine, “we will now have to take a pause, but the time will come when the decision will be made.”8 Nor has there been any evolution in those views. In late March 2007, when he commented on a bill endorsing Ukrainian membership in NATO which the U.S. Congress had just adopted,Yanukovych said, “Ukraine is not ready to join NATO at the moment.”

At Riga, allies “reaffirm(d) the importance of the NATO-Ukraine Distinctive Partnership” and welcomed the progress in Intensified Dialogue, and allies noted with appreciation “Ukraine’s substantial contributions to our common security, including through participation in NATO-led operations and efforts to promote regional cooperation.” They also emphasized their determination “to continue to assist, through practical cooperation, in the implementation of far reaching reform efforts, notably in the fields of national security, defense, reform of the defense industrial sector and fighting corruption.”9 While active and widespread cooperation between NATO and Ukraine continues, for the time being, for the reasons noted above, the issue of Membership Action Plan status for Ukraine and Ukraine’s possible accession to the Washington Treaty are on hold.

Benefits

Looking ahead, however, it is useful to consider the benefits that Ukraine could expect to derive from NATO membership. Most of these are benefits that all allies enjoy; others are specific to Ukraine.

Collective Defense

A key benefit is that, as an ally, Ukraine would enjoy the collective defense guarantees provided by Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. That is, all other allies would be committed to responding to an attack on Ukraine as attack on them.10 Article 5 provides credible deterrence against any state contemplating attacking an ally, which was so important – and successful − during the Cold War. Collective defense remains a core function of NATO and a core benefit of NATO membership despite the fact that an attack on an ally is regarded as highly unlikely under present and foreseeable circumstances. Nevertheless, in that unlikely eventuality, all allies would be obligated by the Washington Treaty to respond. In addition, of particular relevance to Ukraine, energy security is increasingly high on the agenda of individual allies and is likely to a focus of attention in a new Strategic Concept, which could be adopted at the 60th Anniversary Summit expected in 2009.

Defense at Less Cost

Directly related to collective defense are the greatly diminished costs of assuring national defense for NATO allies compared to what they would have to spend on defense without NATO. The costs include an ally’s contribution to common and joint funding, achieving the agreed target of defense expenditures of 2% of GDP and the costs of participating in NATO operations (subsumed under the 2% GDP target). (All told the costs to allies of supporting NATO’s common budgets are less than half of one percent of their overall defense expenditures.) While the direct NATO-related costs would go up with membership, overall national defense expenditures could be expected to decrease. The key point is that it is substantially cheaper to assure defense as a member of NATO than to have to undertake an all-azimuth individual national defense effort. The cost of defense depends, of course, on the security environment, and in the case of Ukraine, the state of relations with Russia would be a key factor. A good relationship with little need for concern about Ukraine’s borders with Russia would mean lower defense costs.

Collective Security

Among the many changes that have taken part since the end of the Cold War, NATO’s evolution into an organization that plays a role in collective security, as well as collective defense, is of particular importance.11 NATO has been developing the capacity to deal with a wide range of emerging security concerns deemed important by its members. The overall process of NATO transformation, including its new roles and the many different ways in which NATO contributes to international peace and security are evidence of this evolution. Participating in an organization which is undertaking tasks of importance to Ukraine in the Euro-Atlantic area and beyond would be a significant benefit for Ukraine. Ukraine is, of course, already making important contributions to NATO-led operations.

Full participation in decision making

Another essential difference (in addition to Article 5 guarantees) between the strategic partnership which Ukraine now enjoys with NATO and membership in the alliance, would be full participation in NATO decision making. Although Ukraine already participates in decisions related to its special relationship with NATO and participates in “decision-shaping” (not decision making) related to NATO-led operations to which it contributes, the right to participate fully in alliance decisions across the whole spectrum of NATO issues and operations would be a key benefit. This means that Ukraine would be able to have a direct impact on the choices that allies make. Stemming from geo-strategic differences and the magnitude of their contributions to NATO operations, allies have different degrees of influence on NATO decisions, but in the final analysis, all allies enjoy the protection provided by the requirement for consensus, and no ally can force NATO to do things that another ally opposes. U.S. inability to obtain the kind of NATO involvement it wanted in Iraq demonstrates this point clearly.

Enhanced International Influence

Due to its size, population and strategic location, Ukraine is already an important player on the international stage, but this influence can not be taken for granted. Some of Ukraine’s current visibility derives from its efforts to get into NATO and the EU and might be diminished if those objectives (and the efforts required) were abandoned. NATO membership would increase Ukraine’s influence both because of the fact of its membership but also because Ukraine would be perceived to be an influential member of the alliance. Being an ally enhances international influence because of the accurate perception that it is consulting, cooperating and operating with other NATO allies, who exercise great influence. Directly related to this, and not to be underestimated, is the symbolic importance of NATO membership, which would make it clear once and for all that Ukraine belongs – conceptually, in its essence – in the West.

Impetus to Reform

The impetus to reform which derives from the conditionality of seeking NATO membership is also a significant benefit. As President Yushchenko has correctly recognized, NATO membership “is a powerful incentive for the transformation of society, aimed at deepening democracy, strengthening human rights and freedoms,” and a way to move Ukraine into the European mainstream.12 Concerning defense reform, in the White Book 2006, he notes that striving “to achieve the best international standards. … is one of the main motives for Ukraine’s integration policy towards the European Union and NATO.”13

Ronald Asmus, responsible for NATO enlargement in the State Department during the Clinton administration, described how the “golden carrot” of membership worked, “it was striking how often the need to take certain steps in order to qualify for NATO or the EU was used by Western governments or invoked by governments in the region to justify painful or controversial steps.”14 And the reform requirements are both extensive and intrusive enhancing the significance of the conditionality which seeking membership brings with it.15

EU Membership

There is no official link between NATO enlargement and EU enlargement, and the prospects of further EU enlargement are now considerably dimmer due to the impasse over the constitutional treaty and enlargement fatigue. And some EU members have also indicated their reservations about Ukrainian EU membership. Nevertheless all Ukrainian parties are united in support of EU membership, there is widespread public support, and NATO membership has been perceived, arguably, as a factor that would boost Ukraine’s chances for EU membership. Some consider that since most EU members are also NATO members, they would be more likely to support Ukraine’s EU aspirations if Ukraine were an ally. Nevertheless, prospects for EU membership do not seem bright. On the eve of the 18 May 2007 EU-Russia Summit, the EU High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy, Javier Solana, reportedly said in an interview to Novyee Izvestia that: “The Republic of Moldova as well as Ukraine and Georgia have no chances of becoming EU members.”16

Economic Growth and Foreign Direct Investment

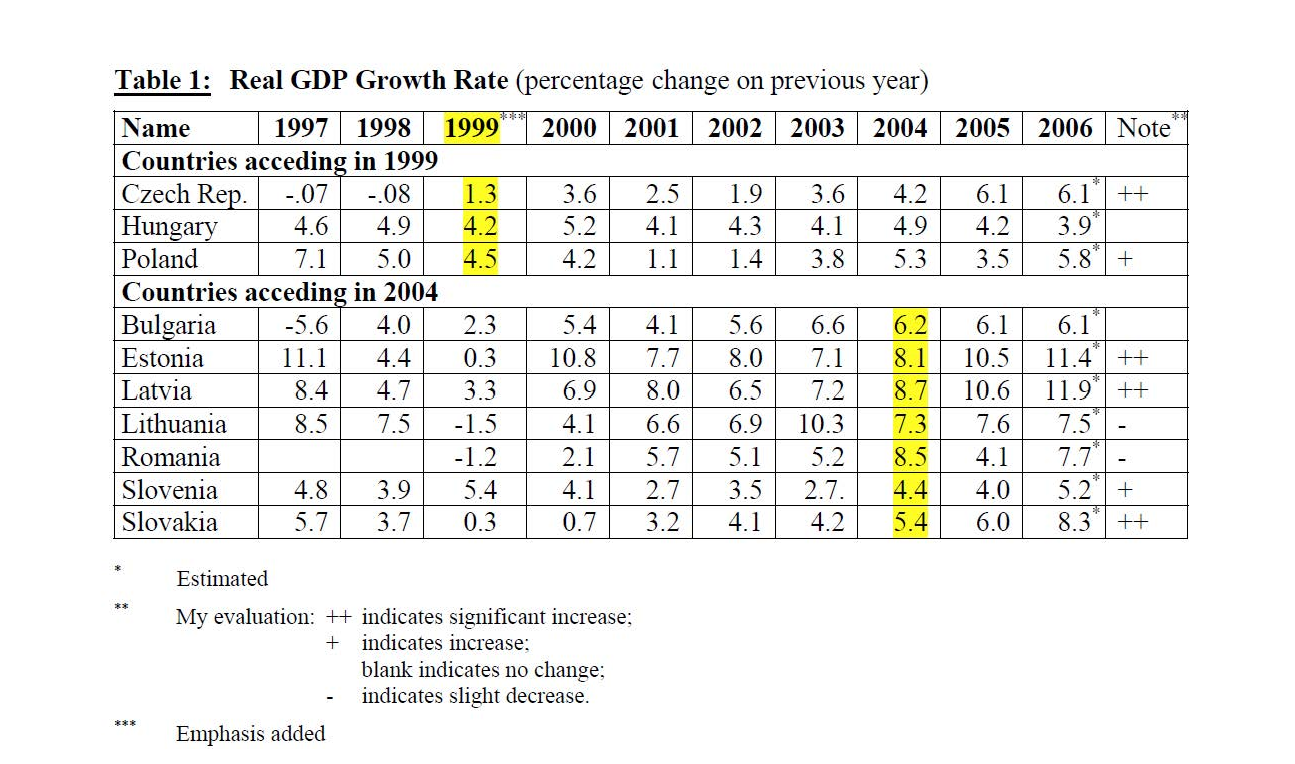

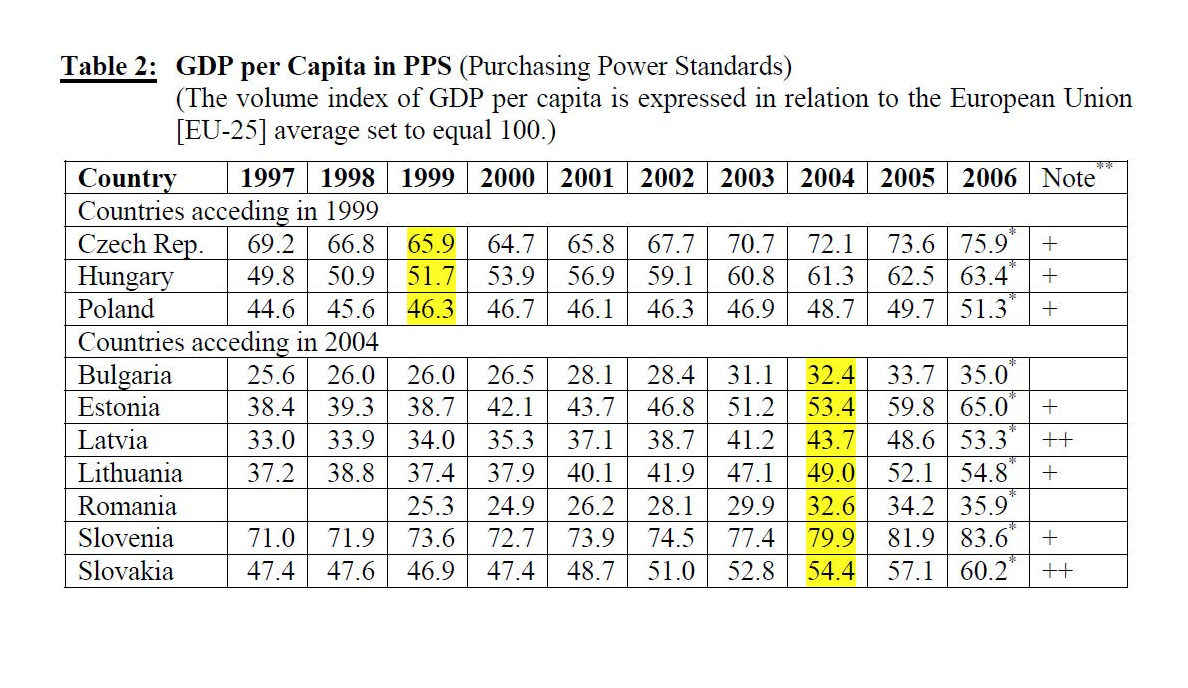

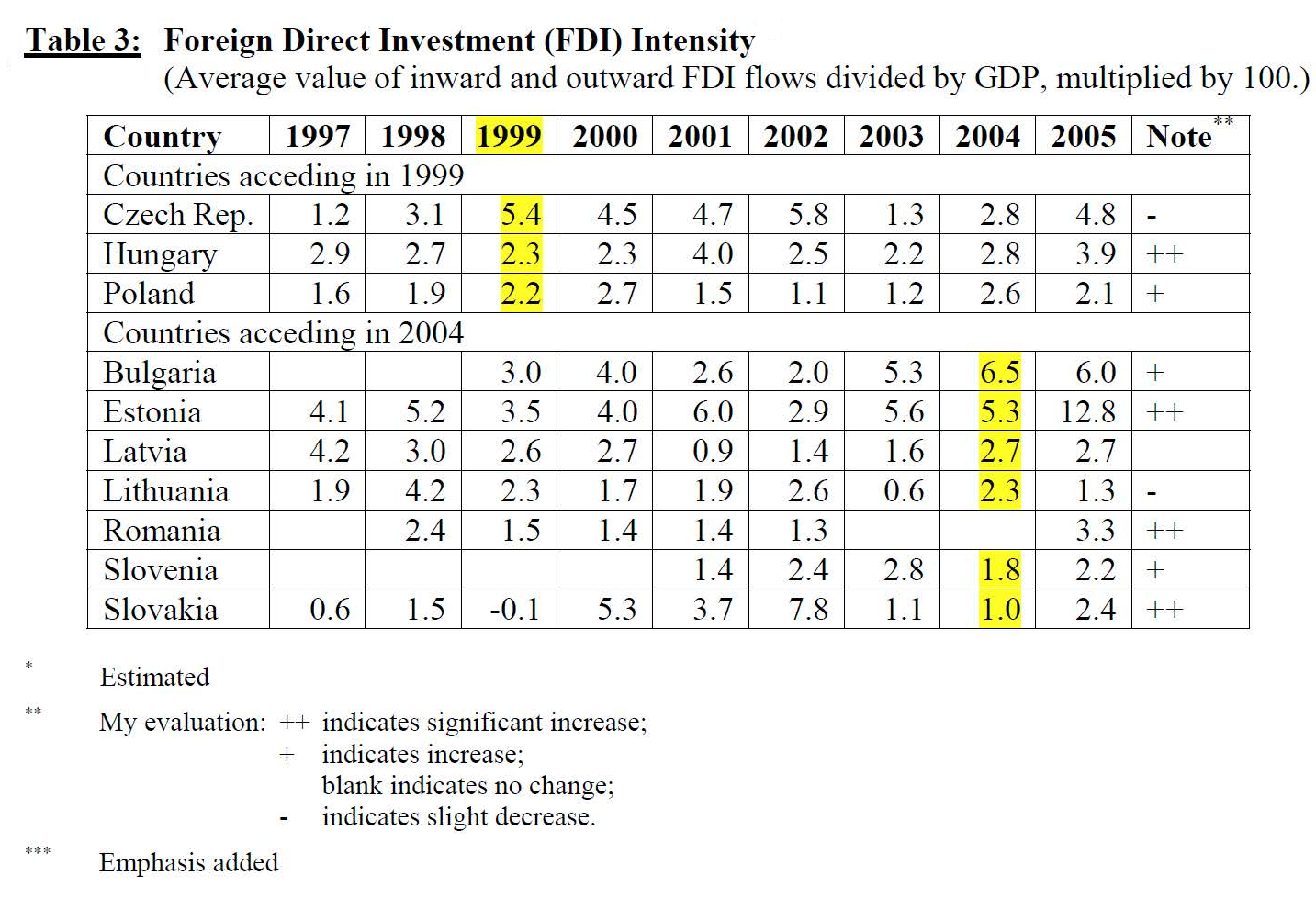

In light of Ukraine’s rapid GDP growth (6.8 % in 2006) and rapid increase in industrial production, the impact of membership on economic growth and increased foreign direct investment is less significant, than would be the case for other aspirant countries. In any case, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between NATO membership and economic growth or increased foreign direct investment among other reasons, because it is so difficult to isolate the impact of NATO membership from the many other factors involved. Nevertheless, it is widely believed that reflecting greater stability and security resulting from the process of joining the alliance and then membership, there is a resulting increase in investor confidence and in economic growth and foreign direct investment following becoming an ally. The three tables at Annex appear to support this view.17

Costs

Obviously NATO membership is not free of risks and costs. Some of these are directly related to the benefits already described above.

Shared Risks and Burdens

Sharing risks,burdens and alliance solidarity are key principles on which NATO is based. As an ally, Ukraine would share risks and burdens in a qualitatively and quantitatively different way than it does in its current status of strategic partner. Burdens include collective defense commitments (referred to above) and the expectation that allies will take an active part in non-Article 5 NATO-led operations, where for the most part allies pay the costs of the deployment, engagement and support of their forces.,18 Ukraine is already a significant contributor to NATO-led operations, and is the only partner that actively supports all four current NATO operations/missions.

Sharing Costs

Sharing burdens also includes financial costs. This includes a share of NATO’s common civilian and military budgets and commonly funded NATO Security Investment Program (NSIP), which totals about $2 billion per year. Cost shares are based on the relative Gross National Income (GNI), taking into account the average of market rates and purchasing power parities. Ukraine would also have to participate in the cost of the new headquarters building in Brussels and probably the running costs of the NATO Airborne Early Warning and Control system (AEW&C). There would also be costs associated with maintaining Ukraine’s mission to NATO headquarters in Brussels, which may be larger than the current mission, and at SHAPE (NATO military headquarters) with assigned Ukrainian military personnel. As noted above, however, overall defense costs could be expected to decrease.

Ukraine-Russian Relations

The strategic context of Ukraine-Russian relations is Russia’s newly assertive foreign policy, in its' more active efforts to organize the post-Soviet space, to its liking. Concerning its relations with Russia, Ukraine would both derive benefits but also incur costs from NATO integration. Cooperation with NATO already buttresses Ukraine’s position vis-à-vis Russia. Despite strong Russian opposition to Ukraine’s NATO aspirations (see below), eventual Ukrainian membership in NATO would strengthen Ukraine’s position vis-à-vis Russia, further. As James Sherr has commented, Prime Minister Yanukovych wishes to pursue a policy that promotes Western investment, trade and political support. While he clearly wishes to improve relations with Russia, he has indicated on a number of occasions that the multi-vector policy he favors, which respects Ukraine’s national interest, “will prove difficult unless the West remains firmly in the equation.”19 With recent developments, the pro-West and anti-West contours have become sharper, and NATO has become the symbol of those differences. The counter argument – and the possible high cost – is that Ukrainian integration in NATO would be perceived by Russia as a serious provocation, which would be likely to lead to considerably worsened relations with Russia.

Aligning Policies

Because almost all NATO decision making is by consensus, allies must be willing to compromise and make timely decisions for collective action. This requires a willingness to adapt positions, sometimes on sensitive issues where there are strongly held views. This could result in some loss of freedom of action in the interests of alliance solidarity. But there is, of course, a benefit as well, as noted above, in the ability to affect the outcome of the decision making process. Speaking of “aligning” policies, NATO membership would also cost Ukraine its status as a member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

Demands on State Institutions

Being an ally is demanding in a number of ways. The process of taking full part in the complex and rapidly evolving decision making process places heavy demands on state institutions, a premium on effective inter-agency interaction and cooperation, and on effective interaction with parliament. For example, when there is a requirement for parliamentary agreement on decisions, (such as the deployment of national forces for NATO operations).

Criticism

Another burden that all allies share is criticism of NATO, for its overall policies or when an operation goes wrong; such as, civilian death or injury resulting from a NATO or NATO-led operation. Even though Ukraine may not be directly involved in the operation, or the particular incident, as an ally it would also be seen, by many, to bear some share of the blame.

Misconceptions and “Urban Legends”

In addition to the costs of NATO membership, there are also a number of misconceptions and urban legends about Ukrainian membership in NATO, which are frequently advanced by critics of cooperation with NATO and opponents of Ukrainian NATO membership.

Lack of Collective Response in the Event of an Armed Attack

One “urban legend”20 is that if Ukraine were an ally, it would have to share the burdens of common defense (described above), but without the guarantee of a collective response in the event of an armed attack on Ukraine.21 That is, Ukraine would not enjoy the protection provided to other allies. In fact all current allies enjoy, and all future allies will enjoy, the collective defense guarantees provided by the Washington Treaty.That is, all allies have a treaty commitment to respond to an armed attack against any ally, as an attack against them all, and to assist the ally attacked, including the use of armed force.22 That being said, Article 5 has only been invoked once, in response to 9/11, and it is not possible to predict with certainty how NATO would respond to a future event. Certainly, during the Cold War there was no doubt about how NATO would have responded to an attack on an ally. This inability to predict a response applies, however, to all allies. There are no different categories of allies, some of whom enjoy the collective defense protections of the Washington Treaty and others who do not. One of the great strengths of the alliance has always been that it was credible; that is there was no doubt about the political will or the military capabilities of the alliance to respond, as required by the Washington Treaty, to an attack on any ally. Moreover, short of an actual attack, Article 4 of the Washington Treaty provides that allies will consult “whenever, in the opinion of any of them, the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the Parties is threatened.”23 This provides a mechanism, which has been used, to respond to threats short of an actual attack.

Impact on Ukrainian Defense Industry

Another area where there are serious misconceptions, but also potential costs, is the impact that NATO membership would have on the Ukrainian defense industry. The first argument, which is in the “urban legend” category, is that in order to meet NATO standards and as a NATO member, Ukraine would have to purchase military equipment manufactured by allies (in particular the U.S.) and this would undermine Ukraine’s own military production. This urban legend contains a number of errors. While there is in fact a requirement for allied forces to be interoperable, that is, to be able to operate with each other, there is no requirement for them to have the same kind of equipment (common equipment) or, for them to have equipment manufactured by one ally or another. Interoperable multinational forces require common doctrine and procedures, interoperable communications, information systems (CIS) and other relevant Alliance equipment, and interchangeability of combat supplies, but not common equipment.24

There is, however, an area where the impact of NATO membership on Ukrainian defense industry is particularly difficult to estimate but could be negative: diminution or cessation of defense cooperation by Russia with Ukraine. Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov raised this issue in late 2005, when he said, “It is the sovereign right of every state to join or not join a bloc, but it is also the sovereign right of every state to select its partners for military-technology cooperation.”25 Ukrainian President Yuschenko’s press spokesman Yuri Klyuchkovksy expressed doubts about this statement noting Russia’s traditional pragmatism in such matters. A cessation of military-technical cooperation by Russia would be important for two reasons: (1) the volume of Ukraine defense exports to the Russian Federation and (2) dependency of Ukraine defense industry on imports of components from Russia. Concerning defense exports, 2004 data from the Ministry of Industrial Policy of Ukraine reported that 51.9% of Ukrainian military industrial complex exports went to Russia.26

Concerning weapons components which Ukraine receives from Russia, a late 2005 estimate by lenta.ru was that 80% percent of the components needed by Ukraine defense industry are supplied by Russia.27 Another estimate, also by a Russian source, is that of Ukraine defense sales of $680 million in 2005, nearly $200 million resulted from cooperation with Russia.28 The implication is that cessation of defense cooperation would have a direct impact on nearly $200 million of defense exports. Russia might also turn elsewhere for its own imports from Ukraine. Ukraine’s arms exporter, Ukrspetseksport reported that arms exports had increased by 15 % for 2006 with good prospects for 2007. Exports included: “aircraft and armored vehicles, as well as their parts, high-precision weapons, radio-electronic detection equipment and radars and servicing and upgrading armaments and military hardware.”29 Of particular interest, the report indicated that the biggest customers were in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, but that there were also significant increases in sales to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) .30 It is also worth noting that the Ukrainian defense industry is concentrated in eastern Ukraine, which is the area most hostile to NATO integration.

By way of a conclusion on this point, which could easily be the topic of a full-fledged research paper in itself, on 19 October 2005, the Minister of Defense, Anatoliy Gritsenko, said he hoped Ukrainians would understand that NATO membership would produce “increased industrial cooperation, creation of jobs and solutions to social problems.”31

The Black Sea Fleet

An additional legend is that NATO Membership would prohibit the stationing of foreign forces in Ukraine, in particular the Black Sea Fleet, whose continued stationing in Crimea until 2017 was agreed upon in the 1997 Russia-Ukraine Treaty. There are many unresolved issues regarding the stationing of the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea. Although, it would be difficult to imagine requirements for substantial non-allied military forces in any allied country, other than temporarily, and related to NATO or a NATO-led operation. There is no NATO prohibition for such stationing, if the allied host country were in agreement. There is, however, such a prohibition in the Ukrainian constitution: Article 17 provides that,” The location of foreign military bases shall not be permitted on the territory of Ukraine.”32

New Risks

Another allegation is that NATO membership would result in new risks from international terrorism, directed against Ukraine, or that Ukraine would be drawn into conflicts against its will.33 Countries which became NATO members in 1999 and 2004 have not been the focus of international terrorist attacks. Moreover, Ukraine has already been contributing for some time, and in significant numbers, to NATO-led operations in the Balkans and Afghanistan. Also on 25 May, a Ukrainian frigate, the URS Ternopil, began participating in Operation Active Endeavour , NATO’s anti-terrorist and collective defense operation in the Mediterranean.34 A second ship is expected to follow. Ukraine is also cooperating with NATO and Partnership for Peace countries in the context of NATO’s Partnership Action Plan against Terrorism (PAP-T). One of the dramatic aspects of NATO’s transformation after 9/11 is the extensive focus on defense against terrorism, including policy statements, military doctrine, offensive and defensive military capabilities, technological advances and improvements in consequence management in the event of a terrorist attack. As an ally, Ukraine would benefit from the additional security that these developments imply, and NATO membership would also enhance the contribution that Ukraine could make in combating international terrorism.

Concerning the risk of being drawn into a conflict against its will, as already noted, as an ally Ukraine would participate fully in NATO’s consensus-based decision making, which would preclude NATO undertaking any operation that Ukraine opposed. Ukraine would, like all other allies, have a binding obligation to respond to an armed attack on an ally.

Challenges

In considering Ukraine’s possible membership in NATO, it is also useful to examine briefly some of the key challenges that Ukraine faces. When faced with a decision on whether to extend an invitation to accession to the Washington Treaty, NATO must ask, in essence, three questions: Are they ready? Are we ready? Will integration increase stability in the region? The first is technical, and the second two are political, but all represent challenges to Ukrainian membership.

National Policy

An essential ingredient in the successful accession of other aspirant countries has been the commitment, will and drive of the national authorities to push the difficult process forward.35 In the case of Ukraine, the absence of agreement at the level of the national government on the desirability of NATO membership is a major challenge. Until such agreement can be reached, which seems unlikely under present circumstances, cooperation with NATO will continue, but progress toward Membership Action Plan status and accession will not.

Public Opinion

A key related challenge is the negative opinion of the Ukrainian public about NATO. Due to lack of interest and information, persistence of Cold War stereotypes and aggressive criticism of NATO and of cooperation with NATO, among other reasons, a large majority of the population opposes membership in NATO. According to press accounts, at the end of 2005, only 16% of the population supported membership in NATO.36 More recently, in mid-July 2007, according to an Interfax-Ukraine report of the Yaremenko Ukrainian Institute for Social Studies and Social Monitoring Center survey, found that 57 % of respondents opposed Ukraine's accession to NATO, while only 19.9 % supported NATO membership. The survey also reported that 24.7 % of Ukrainians believe Ukraine should join the European Union and 43.4 % support a Ukrainian union with Russia and Belarus.37 Other surveys in 2006 had come up with similar results regarding opposition to NATO membership.38 Support continues to be particularly low in the eastern and southern parts of the country where criticism of relations with NATO remains high.

Two additional problems increase the severity of this challenge. The first is the provision in the “Universal” agreement of 3 August 2006, which established the coalition framework, “to take a decision on NATO accession following a nation-wide referendum, which is to be conducted in Ukraine upon completion of all relevant procedures.” This heightens the importance of the already important requirement to improve public support. A second problem is the disbanding by the new government of the Interdepartmental Committee on Euro-Atlantic integration and the cutting of funds by 40% for the two NATO information programs, which the government was conducting.39 This makes it more difficult to provide accurate information about NATO to the public.

It is, of course, up to the people of Ukraine to determine what is in their best interests. Hopefully, they will do so on the basis of clear, accurate and readily available information. The meeting between the NATO Ministers of Defense and the Ukrainian Minister of Defense Grytsenko on the NATO Ukraine Commission, on 14 June 2007, recognized the problem posed by lack of sufficient information by stressing “their determination to continue to develop this strategically important partnership, including through reinforcing efforts to assist Ukraine in conducting public information campaigns about NATO and its roles.”40

Commenting on Prime Minister Yanukovych’s statement to the North Atlantic council, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Fried made clear that a decision about whether NATO integration is a good idea is up to the people of Ukraine, a view that one can safely assume all allies would agree with. He said, “I was not alarmed at all by Prime Minister Yanukovych’s statement of desire to cooperate with NATO, but not push as fast toward membership. He is reflecting what I think is a genuine lack of consensus in Ukraine. Why should NATO, or why should the United States force Ukraine to make those decisions? I don’t want countries in NATO unless they want to be in NATO … Let’s let Ukraine sort it out and let them realize that we’re not trying to grab them or trick them. Let them work through this issue, and in the meantime let’s cooperate with Ukraine as best we can.”41 Secretary General de Hoop Scheffer made the same point at the informal meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, at the level of foreign ministers on 27 April 2007, “NATO’s doors, to an even closer relationship, remain open, but it is ultimately up to Ukraine’s people, and their elected leaders, to determine the country’s future path with NATO.”42

Reform

Continuing the process of political, economic, legal and defense reform is an additional major challenge. There has been progress in some areas, which the Freedom House index for 2006 reflects, but less satisfactory progress in other areas. Freedom House assigned Ukraine an overall democracy score in 2006 of 4.21 (on a scale of 1-7 with 1 as the highest level of democratic progress) which was lower than the 1997 ranking (4.00).43 The 1977 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index (CPI) give Ukraine a perception of corruption score of 2.8 (on a scale of 10, which is least corrupt) and a country rank of 99, not at the bottom but close.44 Neither of these indicators are perfect instruments, but they do provide a useful ball-park overview of the reform process.

In the area of defense reform, there has been considerable progress, including the elaboration and promulgation of key policy documents: The State Program for the Development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine for 2006 – 2011, The Strategic Concept of Employment of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the Strategic Plan of Employment of the Armed force of Ukraine and the White Book 2006 “Defence Policy of Ukraine.” As reported in the White Book, concrete progress also included increasing professionalism, providing interagency coordination, upgrading the command and control system, improving the structure and strength of the armed forces and improving combat readiness.45

Ukraine continues to cooperate actively to implement its Annual Target Plan and is the only partner country in which NATO is involved in supporting both defense reform and comprehensive security sector reform. On the other hand, there has been concern that 50% cuts in the reform budget of the armed forces would inhibit the reform process.46 Since the cuts were made, some supplemental funds have been made available, and additional funds may become available from the sale of surplus defense property.

Russia

Geography, geology and history require that Ukraine get along with its huge neighbor. That requirement, the influential role that Russia plays vis-à-vis Ukraine and within Ukraine, increasingly autocratic rule in Russia and Russia’s increasing assertiveness towards its neighbors magnify the importance of the Russian reaction to Ukraine’s NATO aspirations. Moreover, as was the case for the 1999 and 2004 rounds of enlargement, how to deal with Russia will remain one of the most difficult issues to address successfully.

The very negative Russian reaction so far and its hostility to NATO enlargement for Ukraine (and Georgia) have been clear. In February 2005, State Duma Foreign Relations Committee Chair Kosachev said the real problem in Russia-Ukraine relations “is the Ukrainian defense minister’s statement on the accession to NATO.”47 Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov made a similar point to the State Duma, “We have said more than once that every country has the right to make sovereign decisions on who will be its partner in the international arena …. At the same time, the acceptance into NATO of Ukraine and Georgia will mean a colossal geopolitical shift, and we assess such steps from the point of view of our interests.”48 Subsequently, by a vote of 435 to 0, with one abstention, the State Duma adopted a resolution criticizing Ukraine's plans to join NATO and stating that this would “lead to very negative consequences for relations between our fraternal peoples.”49 More recently, in his 10 February 2007 statement at the Munich Security Conference, President Putin made Russia’s unhappiness over NATO expansion very clear. “NATO expansion is a serious factor which reduces the level of mutual trust,” he said and added, “We have the right to ask against whom is this aimed?”50

One analyst cataloged Russian current tactics towards Ukraine as follows: “1) ignore Kyiv’s pro-Western foreign policy, especially its NATO ambitions, at official level; 2) foment destabilizing developments inside of Ukraine, deepening the historical division of the country and halting Ukraine’s drive to NATO; 3) use direct economic, social, and cultural pressure as instruments of foreign policy; and 4) offer help in providing Ukraine’s security through different forms of cooperation with the CIS or through bilateral channels.”51

Conclusion

The complex challenge then is for Ukraine to reach a decision on whether NATO membership is in Ukraine’s (best) interest. If so and, if that determination is positive, to build the necessary internal political consensus, successfully market itself to NATO allies, and develop the necessary rapprochement with Russia. What seemed to be within grasp a few years ago, now presents a much more difficult picture.

This paper has sought to consider some, but not all, of the principle benefits and costs of Ukrainian membership in NATO. Although I have tried to address these issues objectively and to present arguments concerning both the benefits and costs, I am sure that it has been clear that my view is that the benefits, far outweigh the costs. My hope, therefore, that Ukraine will successfully address the challenges which inhibit progress toward NATO membership. I hope that this paper will serve as encouragement to take more decisive action, to achieve that goal.

Annex

Economic Indicators

The following three tables are intended to shed light on the possible relationship between NATO membership and economic growth and foreign direct investment. As noted above, they are not intended to suggest a causal relationship, and the apparent correlation may derive from other factors. Nevertheless, the tables seem to support the commonly held view that membership in NATO increases investor confidence and contributes to increased economic growth. Table 152. Table 253. Table 354.

For Academic Citation

John Kriendler, “Ukrainian Membership in NATO: Benefits, Costs and Challenges,” Marshall Center Occasional Paper, no. 12, July 2007, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/occasional-papers/ukrainian-membership-nato-benefits-costs-and-challenges.

Notes

1 NATO, “Charter on a Distinctive Partnership between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Ukraine,” Madrid, 9 July 1997, NATO Basic Texts, www.nato.int/docu/basictext/ukrchrt.html; accessed 21 July 2004, hereafter referred to as “Charter.”

2 Article 10 of the Washington Treaty states that: “The Parties may, by unanimous agreement, invite any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area to accede to this Treaty.”

3 All are available at http://www.nato.int/.

4 An analysis of the current political situation in Ukraine is beyond the scope of this paper, but see James Sherr, “Ukraine: Prospects and Risks,” Conflict Studies Research Centre, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 06/52, October 2006, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom and his previous publications for the Conflict Studies Research Center. In addition see Taras Kuzio, “Civil Military Relations Dominate Ukraine’s Political Crisis,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 1 June 2007, http://www.cfr.org/publication/11181/kuzio.html?breadcrumb=%2Fregion %2F336%2Fukraine; accessed 1 June 2007, and Taras Cuzio and Lionel Beehne, “Orange Revolution ‘Over But Not a Failure,’” Council on Foreign Relations, 27 July 2006. http://www.cfr.org/publication/11181/kuzio.html? breadcrumb=%2Fregion%2F336%2Fukraine; accessed 1 June 2007.

5 “Charter,” Op. cit., paragraph 1.

6 NATO, Statement following the elections in Ukraine by NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, 27 December 2004, http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2004/p04-175e.htm; accessed 1 June 2007.

7 NATO, “NATO Ukraine Relations: Security Cooperation and Support for Reform,” http://www.nato.int/issues/ nato-ukraine/topic.html; accessed 22 May 2007.

8 NATO, “Ukraine Prime Minister visits NATO,” NATO Update, 14 September 2006, http://www.nato.int/docu/ update/2006/09-september/e0914b.htm, accessed 15 September 2006.

9 NATO, Riga Summit Declaration, 29 November 2006, http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2006/p06-150e.htm, accessed 1 June 2007, paragraph 39.

10 Article 5 provides that, “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defense recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.”

11 Adam Roberts has defined collective security as: “A system – regional or global – in which each state accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and agrees to join in a collective response to threats to and breaches of the peace.”

12 Associated Press Newswires, “NATO secretary general says Ukraine must carry out reforms before joining alliance,” 19 October 2005.

13 Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, “White Book 2006, Defence Policy of Ukraine,” Kyiv 2007, p. 3.

14 Ronald D. Asmus, “A Strategy for Integrating Ukraine into the West,” Conflict Studies Research Center, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 06/06, April 2004, p. 3.

15 Areas included in the NATO-Ukraine Annual Target Plan include: internal political issues, foreign and security policy, defense and security sector reform, public information, information security and economic and legal issues.

16 Reported, MD, “Javier Solana says Moldova has no chances of joining the EU,” http://www.azi.md/print/44396/ En; accessed 2 June 2007

17 The tables are simplified versions, which I have drawn from EU statistics for all European countries. I have added an additional column with a subjective evaluation of the degree of change.

18 In general terms, the principle is that costs lie where they fall; that is, the nation providing forces for an operation pays all costs. There are some exceptions concerning theater level enabling costs and initial short notice deployment of the NATO Response Force.

19 James Sherr, “Ukraine: Prospects and Risks,” Conflict Studies Research Centre, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 06/52, October 2006, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, p. 3.

20 According to Merriam Webster Online Dictionary, an urban legend is “an often lurid story or anecdote that is based on hearsay and widely circulated as true.”

21 Elena Kovalova, Ukraine’s Role in Changing Europe in The New Eastern Europe: Uniting or Dividing Europe and Eurasia? / Daniel Hamilton and Gerhard Mangott (Eds.), Washington, D.C.: SAIS, The John’s Hopkins University, 2007, pp. 173-197, p. 9.

22 NATO, Washington Treaty, Article 5, http://www.nato.int/docu/basictxt/treaty.htm; accessed 25 May 2007.

23 NATO, May 2007. 25 NATO, Washington Treaty, Article 4.

24 NATO, “NATO Logistics Handbook,” Chapter 17, http://www.nato.int/docu/logi-en/1997/lo-1705.htm; accessed 25 May 2007.

25 Cited in Victor Yasmann, “Russia/Ukraine: Could Gas Spat Impact Military Cooperation?” Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, 16 December 2005.

26 Valentin Badrak, Sergeĭ Zgurets, Sergeĭ Maksimov, “The cult: weapons business in Ukrainian” (“Kul't: oruzheĭnyĭ biznes po-ukrainski.”) Kiev: Defense-Express, 2004, p. 288.

27 Victor Yasmann, op. cit.

28 Yuri Zaitsev, “Obituary for Ukrainian defense industry,” Ria Novotsi, June 2006, http://www.globalsecurity.org/ wmd/library/news/ukraine/2006/ukraine-060614-rianovosti03.htm; accessed 31 May 2007.

29 BBC Monitoring service, “Ukraine's Arms Exporter Reports Growing Trade” Text of report by Ukrainian news agency UNIAN, 27 December 2006.

30 Ibid.

31 Reuters News, “Contact should help NATO image in Ukraine,” 19 October 2005.

32 Constitution of Ukraine, Adopted at the Fifth Session of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine on 28 June 1996, http:// www.rada.gov.ua/const/conengl.htm; accessed 25 May 2007, Article 17.

33 Kovalova, op. cit., p. 9.

34 NATO, “Ukrainian ship joins NATO counter-terrorist operation,” NATO News, http://www.nato.int/docu/ update/2007/05-may/e0530a.html; accessed 31 May 2007.

35 Ronald D. Asmus, “A Strategy for Integrating Ukraine into the West,” Conflict Studies Research Center, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 06/06, April 2004, p. 3.

36 Karl Heinz Kamp, “Ukraine II,” International Herald Tribune, 11 July 2006.

37 Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, “Poll Says Ukrainians Prefer Russia to EU, NATO,” RFE/FL Newsline, 26 July 2007, http://www.rferl.org/newsline/3-cee.asp, accessed 26 July 2007.

38 Interfax Ukrainian News (Russia), “NATO accession and idea of federation in Ukraine unpopular among public - poll,” 28 January 2006. During September 22-28, 2006 the Sociological Service of the “Ukrainian Centre for Economic and Political Studies Olexander Razumkov” (http://www.uceps.org/) conducted a survey in all regions of Ukraine, Kyiv and Crimea, http://www.ji-magazine.lviv.ua/kordon/nato/2006/arhiv2006.htm; accessed 24 May 2007.

39 James Sherr, “Ukraine: Prospects and Risks,” Conflict Studies Research Centre, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 06/52, October 2006, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, p. 3.

40 NATO, “Chairman’s Statement,” Meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Commission in Defense Ministers Session, 14 June 2007, NATO Press Release, http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2007/p07-068e.html; accessed 15 June 2007.

41 Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs NATO/Riga Summit Issues, Roundtable with European Journalists Washington, DC, October 4, 2006 on line at http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/rm/ 73756.htm, accessed 4 November 2004.

42 NATO, “Introductory remarks by the Secretary General, Informal meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Commission at the level of Foreign Ministers,” NATO speeches, www.nato.int/docu/speech/2007/s070427a.html; accessed 28 April 2007.

43 See Freedom House, “Nations in Transition 2006,” http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=17&year= 2006; accessed 31 May 2007.

44 Transparency International's Global Corruption Report 2007, http://www.transparency.org/content/download/ 19093/263155; accessed 28 May 2006, p. 328.

45 White Book 2006, op. cit., pp. 9 - 14.

46 James Sherr, “Ukraine: Prospects and Risks,” Conflict Studies Research Centre, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 06/52, October 2006, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, p. 3.

47 Itar-Tass, 7 February 2005.

48 Associated Press, “Russia calls NATO plans ‘colossal’ shift,” 8 June 2006.

49 Ibid.

50 Vladimir Putin, Statement at the 43rd Munich International Security Conference, 10 February 2007.

51 See Elena Kovalova, Ukraine’s Role in Changing Europe, in The New Eastern Europe: Uniting or Dividing Europe and Eurasia? / Daniel Hamilton and Gerhard Mangott (Eds.), Washington, D.C.: SAIS, The John’s Hopkins University, 2007, pp. 173-197.

52 European Commission, Eurostat, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page?_pageid=1996,39140985&_dad= portal&_schema=PORTAL&screen=detailref&language=en&product=STRIND_ECOBAC&root=STRIND_EC OBAC/ecobac/eb012; accessed 23 May 2007.

53 European Commission, Eurostat, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page?_pageid=1996,39140985&_dad= portal&_schema=PORTAL&screen=detailref&language=en&product=STRIND_ECOBAC&root=STRIND_EC OBAC/ecobac/eb011; accessed 23 May 2007.

54 European Commission, Eurostat, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page?_pageid=1073,46870091&_dad= portal&_schema=PORTAL&p_product_code=ER066; accessed 23 May 2007.

About the Author

John Kriendler is professor of NATO and European Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.

He lectures on NATO, European security issues and the United Nations, and teaches a core seminar and an elective course on “NATO: Strategic and Operational Perspectives.”

Mr. Kriendler was born in New York City. He was a U.S. naval officer from 1961- 1964. As a career foreign service officer from 1970 – 1993, he served in U.S. embassies in Buenos Aires, Bogota and Caracas, in the State Department, at the U.S. Mission to the UN, and at the U.S. Mission to UNESCO. He was a member of the NATO international staff as deputy assistant secretary general for political affairs and, subsequently, as head, council operations. He has been at the Marshall Center since 2002.

Mr. Kriendler earned a B.A. in government from Cornell University in 1959 and an M.A. in politics from the University of Massachusetts in 1967. He also pursued graduate studies in political science at Yale, the University of Freiburg, the Free University (Berlin), NYU (completed course work for a Ph.D.) and Columbia University.

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies is a leading transatlantic defense educational and security studies institution. It is bilaterally supported by the U.S. and German governments and dedicated to the creation of a more stable security environment by advancing democratic institutions and relationships, especially in the field of defense; promoting active, peaceful security cooperation; and enhancing enduring partnerships among the countries of North America, Europe, and Eurasia.

The Marshall Center Occasional Paper Series seeks to further the legacy of the Center’s namesake, General George C. Marshall, by disseminating scholarly essays that contribute to his ideal of ensuring that Europe and Eurasia are democratic, free, undivided, and at peace. Papers selected for this series are meant to identify, discuss, and influence current defense related security issues. The Marshall Center Occasional Paper Series focus is on comparative and interdisciplinary topics, including international security and democratic defense management, defense institution building, civil-military relations, strategy formulation, terrorism studies, defense planning, arms control, stability operations, peacekeeping, crisis management, regional and cooperative security. The Marshall Center Occasional Papers are written by Marshall Center faculty and staff, Marshall Center alumni, or by individual, invited contributors, and are disseminated online and in a paper version.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, the U.S. Department of Defense, the German Ministry of Defense, or the U.S. and German Governments. This report is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.